fotofrog\iStock

Until recently, your typical banker was someone whose main job was to accept deposits, cash checks, and dispense basic financial advice. But now that job hardly exists anymore—at least not as we once knew it. Today’s front-line bank workers—tellers, loan interviewers, and customer-service reps—earn far too little money to be considered “bankers” in the traditional sense of the word. And though they still collect and dispense money, their main job involves hawking credit cards and loans you probably don’t need.

Rank-and-file bank workers are both causes and symptoms of America’s widening economic divide, says Aditi Sen, the author of Big Banks and the Dismantling of the Middle Class, a report released today by the Center for Popular Democracy. Based on union organizer interviews with hundreds of workers in the industry, Sen found that front-line bank workers often face quotas for hawking potentially exploitive financial products, often to low-income customers, even though the workers themselves barely qualify as middle class. “We can definitely see bank workers as part of the same continuum of issues facing all low-wage workers,” she says.

Banks are, of course, notorious for squeezing profits from their employees and customers. In 2011, the Federal Reserve Board fined Wells Fargo $85 million for forcing workers to sell expensive subprime mortgages to prime borrowers. And in late 2013, a judge slapped Bank of America with a $1.27 billion penalty for its “Hustle Program,” which rewarded employees for producing more loans and eliminating controls on the loans’ quality.

Yet, by some accounts, these sorts of practices are getting worse. In a 2013 study by the union-backed Committee for Better Banks, 35 percent of low-level bank workers surveyed reported increased sales pressure since 2008, and nearly 38 percent stated that there was no real avenue in the workplace to oppose such practices. One HSBC bank employee, according to the study, reported that workers who failed to meet their sales goals had the difference taken out of their paychecks.

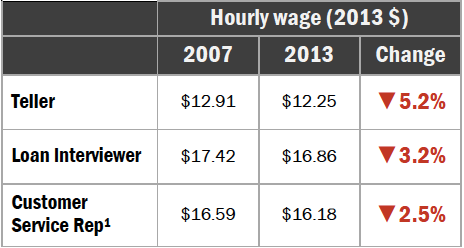

The increasing sales pressure comes at a time when the fortunes of the banks and their low-level workers have diverged widely. Bank profits and CEO pay have rebounded to near record levels while wages for front-line workers are stuck in the gutter.

And that’s not all. Nearly a quarter of bank workers surveyed in 2013 reported that their benefits had been cut since 2008, and 44 percent reported that their medical and life insurance was inadequate. A recent University of California-Berkeley study found that 31 percent of bank tellers’ families rely on public assistance at an annual cost of $900 million to taxpayers.

There are several factors in all of these woes. Mergers and consolidation have led some retail banks to shutter branches and lay people off. Many banks have outsourced customer-service jobs to overseas call centers, and the rise of internet and smartphone banking has further slashed demand for flesh-and-blood tellers. In other words, it’s basically the same mix of foreign and technological competition that has concentrated wealth and depressed middle-class wages throughout the economy. And it means that banks can get away with paying people less, and demanding more in return.

But now the Committee for Better Banks is trying to cultivate common cause between low-level bank workers and the customers they’re forced to target. The interviews featured in the new report show that many bank workers strongly oppose the sales quotas as unfair and exploitive. For instance:

A teller at a top-five bank reports that she is subject to stringent individual goals on a daily basis: If she does not make three sales-points (selling someone a new checking, savings, or debit card account) each day in a month, she gets written up.

Customer service representatives at a call center for another major bank report that each individual has to make 40 percent of the sales of the top seller to avoid being written up. Selling credit cards counts more towards sales goals than helping someone open up a checking account or savings account, thereby crafting skewed incentives based on the profitability of a product sold, not on how well it matched the needs of a customer.

“A lot of time people would call and already have one, two, or three credit cards with us,” says Liz, a member of the Committee for Better Banks who worked in a Bank of America call center for five years and did not want to give her last name. “They might have a situation where they are low on funds and we end up pushing another credit card on them. There was one guy who had three credit cards and I ended up pushing a fourth on him, even though I knew that was not good for him; he would just be in more debt. But if didn’t, I would end up being put in a reprimand.”

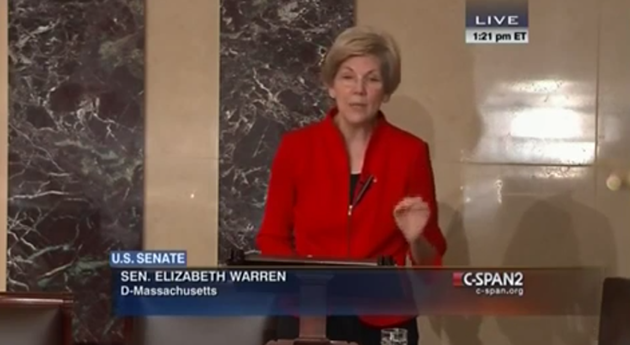

On Monday, members of the Committee for Better Banks will converge in Minnesota’s Twin Cities to deliver a petition to bank offices demanding better pay and more stable work hours for rank-and-file workers, and an end to sales goals that “push unnecessary products on our customers.”