Cleveland police responding to a protest in late MayJohn Minchillo/AP

On Tuesday, Cleveland Mayor Frank Jackson and US Justice Department officials announced sweeping reforms for the Cleveland police department, including provisions overhauling use of force and crisis intervention practices. The changes arrive as questions continue to swirl around two lengthy investigations into the deaths of black suspects at the hands of Cleveland police.

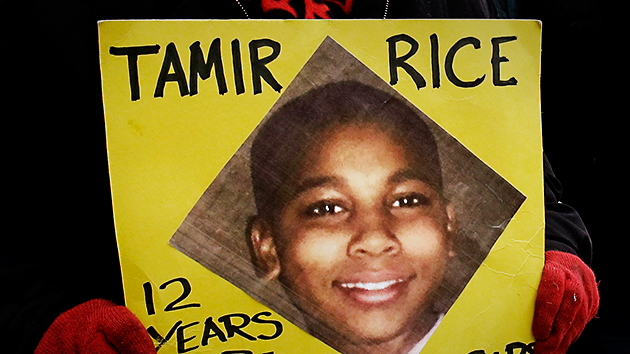

As Mother Jones first reported in mid-May, the officers involved in the shooting of 12-year-old Tamir Rice, which was captured on video and drew major media attention, still hadn’t been questioned by investigators after six months. Another case, which has received less media attention, is that of Tanisha Anderson, a 37-year-old mentally ill woman who died shortly after two Cleveland police officers physically restrained her outside her home last November. Few details have been made public about the case, which was initially reviewed internally by the Cleveland PD. It has since been in the hands of the Cuyahoga County Prosecutor’s Office, which took control of the investigation on February 12, a spokesperson for Mayor Jackson’s office told Mother Jones.

According to the official account released by the Cleveland police department, officers Scott Aldridge and Bryan Myers arrived at Anderson’s home around 10:51 p.m. on November 12, in response to a call about a mentally ill family member. After a discussion with the officers, the account stated, Anderson agreed to be escorted to a hospital for a psychiatric evaluation, but as they approached the police vehicle Anderson “began actively resisting the officers.” After they handcuffed her, Anderson began to kick at Aldridge and Myers, the officers said. “A short time later the woman stopped struggling and appeared to go limp,” they said. The officers called an ambulance to the scene. Anderson was pronounced dead at a nearby hospital less than an hour later.

The police account includes no details about how or why Anderson fell limp on the sidewalk. According to Anderson’s family members, who filed a wrongful death lawsuit against Cleveland on January 7, Anderson suffered from bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Family members who lived with Anderson dialed 911 to request medical assistance after Anderson became disoriented and walked out of her house into the cold, wearing only a nightgown, according to the court filing. After the officers arrived and escorted Anderson to their car, the family says, she began to panic. Family members allege that Aldridge then grabbed Anderson, “slammed her to the sidewalk, and pushed her face into the pavement,” and then pressed his knee on her back and handcuffed her, while Myers assisted in restraining her. Within moments, Anderson lost consciousness, the family members said. The lawsuit also alleges that when family members asked the officers to check on her condition, the officers “falsely claimed she was sleeping” and delayed calling for medical assistance. “During the lengthy time that Tanisha lay on the ground,” the family said, Aldridge and Myers “failed to provide any medical attention to Tanisha.”

Initially, the Cleveland PD conducted an internal administrative review, the details of which remain unknown to the public. In January, the Cuyahoga County Medical Examiner’s office ruled the death a homicide by legal intervention, caused by a “sudden death associated with physical restraint.” Cleveland’s director of public safety Michael McGrath then announced that there would be a hearing for Aldridge and Myers to “determine if disciplinary action is warranted.” (McGrath, previously Cleveland’s police chief, came under criticism following a scathing report last year from the US Justice Department on the Cleveland PD’s use of force and other practices.) That hearing took place on February 13, but the results have not been released, and any potential disciplinary action has been put on hold pending the criminal investigation, a spokesperson for Mayor Jackson’s office told Mother Jones. Officers Aldridge and Myers remain on restricted duty.

The county prosecutor’s office and the Cleveland police department declined to answer questions from Mother Jones about the investigation, including with regard to the length of time it’s taking.

But public pressure for answers—in both the Rice and Anderson cases—has been rising. “It is extremely disconcerting that the families and the public are required to wait so long to find out if the officers will stand trial for the killings,” says Ayesha Bell Hardaway, a law professor at Case Western Reserve University and former Cuyahoga County assistant prosecutor.

David Harris, a law professor at the University of Pittsburgh who writes about police behavior and regulation, adds that since the upheaval in Ferguson last summer, the public’s expectations for investigations into officer-involved killings have begun to change. “One year ago, we probably did not take a lot of notice,” he says. “It’s only since Ferguson, and especially since North Charleston and Baltimore, that we are seeing cases being evaluated and moved more rapidly.”

Unlike other recent killings—including another in Ohio, in which police shot John Crawford—there’s no known video that captured the moments leading up to Anderson’s death. Last December, however, the US Justice Department found that a pattern of misuse of deadly force by the Cleveland police department included “excessive force against persons who are mentally ill or in crisis.” The Cleveland PD fueled community distrust, the DOJ report said, in part by using “force against people in mental health crisis after family members have called the police in a desperate plea for assistance.” It also said that Cleveland officers were not receiving sufficient basic mental health training, and that the department appeared not to have offered any in-service mental health training since at least 2010.

It’s unclear if Aldridge or Myers received any crisis intervention training at Cleveland PD. According to personnel records obtained by Cleveland.com, Aldridge was hired in April 2008, and was suspended for three days without pay in 2013 over a taser incident that involved a female suspect. (He was also one of the officers involved in the 60-car chase that led to the deaths of Timothy Russell and Malissa Williams in 2012.) Myers, a rookie cop, joined the force in 2014, after graduating from the police academy that August in the same class as Timothy Loehmann, the officer who shot and killed Tamir Rice. Cleveland.com reported that Aldridge and Myers’ time at the academy included 16 hours of crisis intervention training.

The lack of video evidence in Anderson’s case may be one reason why it has received less media attention than other officer-involved killings, says Hardaway. “But it goes beyond that,” she adds, pointing to Anderson’s gender and mental illness. According to research by the African American Policy Forum, Anderson’s is one among many other cases of black women killed by police that have gone underreported.