This story first appeared on the TomDispatch website. Photos and reporting by Eduardo García

Something is rotten in the state of Michigan.

One city neglected to inform its residents that its water supply was laced with cancerous chemicals. Another dissolved its public school district and replaced it with a charter school system, only to witness the for-profit management company it hired flee the scene after determining it couldn’t turn a profit. Numerous cities and school districts in the state are now run by single, state-appointed technocrats, as permitted under an emergency financial manager law pushed through by Rick Snyder, Michigan’s austerity-promoting governor. This legislation not only strips residents of their local voting rights, but gives Snyder’s appointee the power to do just about anything, including dissolving the city itself—all (no matter how disastrous) in the name of “fiscal responsibility.”

If you’re thinking, “Who cares?” since what happens in Michigan stays in Michigan, think again. The state’s aggressive balance-the-books style of governance has already spread beyond its borders. In January, New Jersey Governor Chris Christie appointed bankruptcy lawyer and former Detroit emergency manager Kevyn Orr to be a “legal adviser” to Atlantic City. The Detroit Free Press described the move as “a state takeover similar to Gov. Rick Snyder’s state intervention in the Motor City.”

And this spring, amid the hullabaloo of Republicans entering the 2016 presidential race, Governor Snyder launched his own national tour to sell “the Michigan story to the rest of the country.” His trip was funded by a nonprofit (fed, naturally, by undisclosed donations) named “Making Government Accountable: The Michigan Story.”

To many Michiganders, this sounded as ridiculous as Jeb Bush launching a super PAC dubbed “Making Iraq Free: The Bush Family Story.” Except Snyder wasn’t planning to enter the presidential rat race. Instead, he was attempting to mainstream Michigan’s form of austerity politics and its signature emergency management legislation, which stripped more than half of the state’s African American residents of their local voting rights in 2013 and 2014.

As the governor jaunted around the country, Ann Arbor-based photographer Eduardo García and I decided to set out on what we thought of as our own two-week Magical Michigan Tour. And while we weren’t driving a specially outfitted psychedelic tour bus—we spent most of the trip in my grandmother’s 2005 Prius—our journey was nevertheless remarkably surreal. From the southwest banks of Lake Michigan to the eastern tips of the peninsula, we crisscrossed the state visiting more than half a dozen cities to see if there was another side to the governor’s story and whether Michigan really was, as one Detroit resident put it, “a massive experiment in unraveling US democracy.”

Stop One: Water Wars in Flint

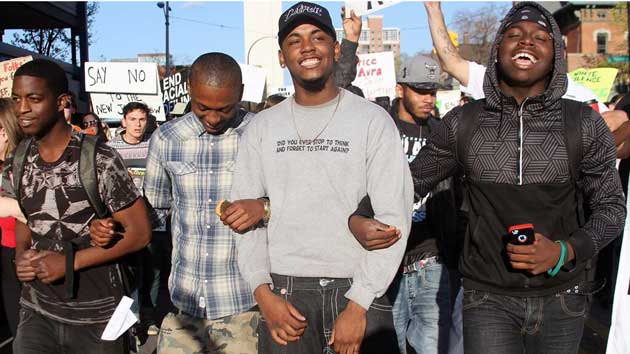

Just as we arrive, the march spills off the sidewalk in front of the city council building.

“Stop poisoning our children!” chants a little girl as the crowd tumbles down South Saginaw Street, the city’s main drag. We’re in Flint, Michigan, a place that hit the headlines last year for its brown, chemical-laced, possibly toxic water. A wispy white-haired woman waves a gallon jug filled with pee-colored liquid from her home tap. “They don’t care that they’re killing us!” she cries.

We catch up with Claire McClinton, the formidable if grandmotherly organizer of the Flint Democracy Defense League, as we approach the roiling Flint River. It’s been a longtime dumping ground for the Ford Motor Company’s riverfront factories and, as of one year ago today, the only source of the city’s drinking water. On April 25, 2014, on the instruction of the city’s emergency manager, Flint stopped buying its supplies from the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department and started drawing water directly from the river, which meant a budgetary savings of $12 million a year. The downside: people started getting sick.

Since then, tests have detected E. coli and fecal bacteria in the water, as well as high levels of trihalomethanes, a carcinogenic chemical cocktail known as THMs. For months, the city concealed the presence of THMs, which over years can lead to increased rates of cancer, kidney failure, and birth defects. Still, it was obvious to local residents that something was up. Some of them were breaking out in mysterious rashes or experiencing bouts of severe diarrhea, while others watched as their eyelashes and hair began to fall out.

As we cross a small footbridge, McClinton recounts how the city council recently voted to “do all things necessary” to get Detroit’s water back. The emergency manager, however, immediately overrode their decision, terming it “incomprehensible.”

“This is a whole different model of control,” she comments dryly and explains that she’s now working with other residents to file an injunction compelling the city to return to the use of Detroit’s water. One problem, though: it has to be filed in Ingham County, home to Lansing, the state capital, rather than in Flint’s Genesee County, because the decision of a state-appointed emergency manager is being challenged. “Under state rule, that’s where you go to redress grievances,” she says. “Just another undermining of our local authority.”

In the meantime, many city residents remain frustrated and confused. A few weeks before the march, the city sent out two notices on the same day, packaged in the same envelope. One, printed in black-and-white, stated bluntly: “Our water system recently violated a drinking water standard.” The second, in flashy color, had this cheery message: “We are pleased to report that City of Flint water is safe and meets US Environmental Protection Agency guidelines… You can be confident that the water provided to you today meets all safety standards.” As one recipient of the notices commented, “I can only surmise that the point was to confuse us all.”

McClinton marches in silence for a few minutes as the crowd doubles back across the bridge and begins the ascent up Saginaw Street. Suddenly, a man jumps onto a life-size statue of a runner at the Riverfront Plaza and begins to cloak him in one of the group’s T-shirts.

“Honey, I don’t want you getting in any trouble!” his wife calls out to him.

He’s struggling to pull a sleeve over one of the cast-iron arms when the droning weeoo-weeooo-weeoo of a police siren blares, causing a brief frenzy until the man’s son realizes he’s mistakenly hit the siren feature on the megaphone he’s carrying.

After a few more tense moments, the crowd surges forward, leaving behind the statue, legs stretched in mid-stride, arms raised triumphantly, and on his chest a new cotton T-shirt with the slogan: “Water You Fighting For?”

Stop Two: The Tri-Cities of Cancer

The next afternoon, we barrel down Interstate 75 into an industrial hellscape of smoke stacks, flare offs, and 18-wheelers, en route to another toxicity and accountability crisis. This one was caused by a massive tar sands refinery and dozens of other industrial polluters in southwest Detroit and neighboring River Rouge and Ecorse, cities which lie along the banks of the Detroit River.

Already with a slight headache from a haze of emissions, we meet photographer and community leader Emma Lockridge and her neighbor Anthony Parker in front of their homes, which sit right in the backyard of that tar sands refinery.

In 2006, the toxicity levels in their neighborhood, known simply by its zip code as “48217,” were 45 times higher than the state average. And that was before Detroit gave $175 million in tax breaks to the billion-dollar Marathon Petroleum Corporation to help it expand its refinery complex to process a surge of high-sulfur tar sands from Alberta, Canada.

“We’re a donor zip,” explains Lockridge as she settles into the driver’s seat of our car. “We have all the industry and a tax base, but we get nothing back.”

We set off on a whirlwind tour of their neighborhood, where schools have been torn down and parks closed due to the toxicity of the soil, while so many residents have died of cancer that it’s hard for their neighbors to keep track. “We used to play on the swings here,” says Lockridge, pointing to a rusted yellow swing set in a fenced-off lot where the soil has tested for high levels of lead, arsenic, and other poisonous chemicals. “Jumping right into the lead.”

As in other regions of Michigan, people have been fleeing 48217 in droves. Here, however, the depopulation results not from deindustrialization, but from toxicity, thanks to an ever-expanding set of factories. These include a wastewater treatment complex, salt mines, asphalt factories, cement plants, a lime and stone foundry, and a handful of steel mills all clustered in the tri-cities region.

As Lockridge and Parker explain, they have demanded that Marathon buy their homes. They have also implored the state to cap emission levels and have filed lawsuits against particularly toxic factories. In response, all they’ve seen are more factories given more breaks, while the residents of 48217 get none. Last spring, for example, the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality permitted the AK Steel plant, located close to the neighborhood, to increase its toxic emissions as much as 725 times. The approval, according to the Detroit Free Press, came after “Gov. Rick Snyder’s business-promoting agency worked for months behind the scenes” lobbying the Department of Environmental Quality.

“Look at this cute little tree out of nowhere over here!” Lockridge exclaims, slowing the car in front of a scrawny plant whose branches, in the midst of this industrial wasteland, bend under the weight of white blossoms.

“That tree ain’t gonna grow up,” Parker responds. “It’s dead already.”

“It’s trying,” Lockridge insists. “Aww, it’s kind of sad. It’s a Charlie Brown tree.”

The absurdity of life in such an environment is highlighted when we reach a half-mile stretch of sidewalk sandwiched between a massive steel mill and a coal-fired power plant that has been designated a “Wellness Walk.”

“Energize your Life!” implores the sign affixed to a chain-link fence surrounding the power plant. It’s an unlikely site for an exercise walk, given that the state’s health officials consider this strip and the nearby park “the epicenter of the state’s asthma burden.”

After a sad laugh, we head for Zug Island, a Homeland Security-patrolled area populated by what look to be giant black vacuum cleaners but are actually blast furnaces. The island was named for millionaire Samuel Zug, who built a lavish mansion there only to discover that it was sinking into swampland. It is now home to US Steel, the largest steel manufacturer in the nation.

On our way back, we make a final stop at Oakwood Heights, an almost entirely vacant and partially razed subdivision located on the other side of the Marathon plant. “This is the white area that was bought out,” says Lockridge. The scene is eerie: small residential streets lined by grassy fields and the occasional empty house. That Marathon paid residents to evacuate their homes in this predominantly white section of town, while refusing to do the same in the predominantly African American 48217, which sits closer to the refinery, strikes neither Lockridge and Parker nor their neighbors as a coincidence.

We survey the remnants of the former neighborhood: bundles of ragged newspapers someone was once supposed to deliver, a stuffed teddy bear abandoned on a wooden porch, and a childless triangle-shaped playground whose construction, a sign reads, was “made possible by generous donations from Marathon.”

As this particularly unmagical stop on our Michigan tour comes to an end, Parker says quietly, “I’ve got to get my family out of here.”

Lockridge agrees. “I just wish we had a refuge place we could go to while we’re fighting,” she says. “You see we’re surrounded.”

Stop Three: The Great White North

Not all of Michigan’s problems are caused by emergency management, but this sweeping new power does lie at the heart of many local controversies. Later that night we meet with retired Detroit city worker, journalist, and organizer Russ Bellant who has made himself something of an expert on the subject.

In 2011, he explains, Governor Snyder signed an emergency manager law known as Public Act 4. The impact of this law and its predecessor, Public Act 72, was dramatic. In the city of Pontiac, for instance, the number of public employees plummeted from 600 to 50. In Detroit, the emergency manager of the school district waged a six-year slash-and-burn campaign that, in the end, shuttered 95 schools. In Benton Harbor, the manager effectively dissolved the city government, declaring: “The fact of the matter is, the city manager is now gone. I am the city manager. I replace the financial director, so I’m the financial director and the city manager. I am the mayor and the commission. And I don’t need them.”

So in 2012, Bellant cancelled all his commitments in Detroit, packed his car full of chocolate pudding snacks, canned juices, and fliers and headed north to support a statewide campaign to repeal the law through a ballot referendum in that fall’s general election. For two months, he crisscrossed the upper reaches of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula, the part of the state that people say looks like a hand, as well as the remote Upper Peninsula that borders Wisconsin and Canada.

“Seven or eight hours a day, I would just knock on doors,” he says.

In November, the efforts paid off and voters repealed the act, but the celebration was short-lived. Less than two months later, during a lame-duck session of the state legislature, Governor Snyder pushed through and signed Public Act 436, a broader version of the legislation that was referendum-proof. Since then, financial managers have continued to shut down fire departments, outsource police departments, sell off parking meters and public parks. In Flint, the manager even auctioned off the plastic Santa Claus that once adorned city hall, setting the initial bidding price at $5.

And here’s one fact of life in Michigan: emergency management is normally only imposed on majority-black cities. From 2013 to 2014, 52 percent of the African American residents in the state lived under emergency management, compared to only 2 percent of white residents. And yet the repeal vote against the previous version of the act was a demographic landslide: 75 out of 83 counties voted to nix the legislation, including all of Michigan’s northern, overwhelmingly white, rural counties. “I think people just internalized that P.A. 4 was undemocratic,” Bellant says.

That next morning, we travel north to the city of Alpena, a 97 percent white lakeside town where Bellant knocked on doors and the recall was triumphant. The farther north we head, the more the landscape changes. We pass signs imploring residents to “Take Back America: Liberty Yes, Tyranny No.” Gas stations feature clay figurines of hillbillies drinking moonshine in bathtubs.

It’s almost evening when we arrive. We spend part of our visit at the Dry Dock, a dive bar overseen by a raspy-voiced bartender where all the political and demographic divides of the state—and, in many ways, the country—are on full display. Two masons are arguing about their union; the younger one likes the protections it provides, while his colleague ditched the local because he didn’t want to pay the dues. That move became possible only after Snyder signed controversial “right-to-work” legislation in 2012, allowing workers to opt-out of union dues and causing a sharp decline in union membership ever since.

Above their heads, the television screen projects intentionally terrifying images of the uprising in Baltimore in response to the police murder of Freddie Gray, an unarmed African American man. “The Bloods, the Crips, and the Guerrillas are out for the National Guard,” comments a carpenter about the unarmed protesters, a sneer of distain in his voice. “Not that I like the fucking cops, either,” he adds.

Throughout our visit, people repeatedly told us that Alpena “isn’t Detroit or Flint” and that they have absolutely no fear of the state seizing control of their sleepy, white, touristy city. When we press the question with the owner of a bicycle shop, the hostility rises in his voice as he explains: “Things just run the way they should here”—by which he means, of course, that down in Detroit and Flint, residents don’t run things the way they should.

Yet, misconceptions notwithstanding, the county voted to repeal Public Act 4 with a staggering 63 percent of those who turned out opting to strike down the law.

Reflecting Bellant’s feeling that locals grasped the law’s undemocratic nature in some basic way, even if it would never affect them personally, one resident offered this explanation: “When you think about living in a democracy, then this is like financial martial law… I know they say these cities need help, but it didn’t feel like something that would help.”

Stop Four: The Fugitive Task Force

The next day, as 2,000 soldiers from the 175th Infantry Regiment of the National Guard fanned out across Baltimore, we head for Detroit’s west side where, only 24 hours earlier, a law enforcement officer shot and killed a 20-year-old man in his living room.

A crowd has already gathered near his house in the early summer heat, exchanging condolences, waving signs, and jostling for position as news crews set up cameras and microphones for a press conference to come. Versions of what happened quickly spread: Terrance Kellom was fatally shot when officers swarmed his house to deliver an arrest warrant. The authorities claim that he grabbed a hammer, prompting the shooting; his father, Kevin, contends Terrance was unarmed and kneeling in front of him when he was shot several times, including once in the back.

Kellom is just one of the 489 people killed in 2015 in the United States by law enforcement officers. There is, however, a disturbing twist to Kellom’s case. He was not, in fact, killed by the police but by a federal agent working with a little known multi-jurisdictional interagency task force coordinated by the US Marshals.

Similar task forces are deployed across the country and they all share the same sordid history: the Marshals have been hunting people ever since the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act compelled the agency to capture slaves fleeing north for freedom. One nineteenth-century newspaper account, celebrating the use of bloodhounds in such hunts, wrote: “The Cuban dog would frequently pull down his game and tear the runaway to pieces before the officers could come up.”

These days, Detroit’s task force has grown particularly active as budget cuts have decimated the local police department. Made up of federal Immigration and Customs officers, police from half a dozen local departments, and even employees of the Social Security Administration office, the Detroit Fugitive Apprehension Team has nabbed more than 15,000 people. Arrest rates have soared since 2012, the same year the local police budget was chopped by 20 percent. Even beyond the task force, the number of federal agents patrolling the city has risen as well. The Border Patrol, for example, has increased its presence in the region by tenfold over the last decade and just two weeks ago announced the launch of a new $14 million Detroit station.

Kevin Kellom approaches the barricade of microphones and begins speaking so quietly that the gathered newscasters crush into each other in an effort to catch what’s he’s saying. “They assassinated my son,” he whispers. “I want justice and I’m going to get justice.”

Yet today, six weeks after Terrance’s death, no charges have been brought against the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agent who fired the fatal shot. Other law enforcement officers who have killed Michigan residents in recent years have similarly escaped punishment. Detroit police officer Joseph Weekley was videotaped killing seven-year-old Aiyana Jones with a submachine gun during a SWAT team raid on her home in 2010. He remains a member of the department. Ann Arbor police officer David Reid is also back on duty after fatally shooting 40-year-old artist and mother Aura Rosser in November 2014. The Ann Arbor police department ruled that a “justifiable homicide” because Rosser was holding a small kitchen knife during the encounter—a ruling that Rosser’s family members and city residents are contesting with an ongoing campaign calling for an independent investigation into her death.

And such deadly incidents continue. Since Kellom’s death, law enforcement officers have fatally shot at least three more Michigan residents—one outside the city of Kalamazoo, another near Lansing, and a third in Battle Creek.

Stop Five: The Unprofitable All-Charter School District

Our final stop is Muskegon Heights, a small city on the banks of Lake Michigan, home to perhaps the most spectacular educational debacle in recent history. Here’s the SparkNotes version. In 2012, members of the Muskegon Heights public school board were given two options: dissolve the district entirely or succumb to an emergency manager’s rule. On arrival, the manager announced that he was dissolving the public school district and forming a new system to be run by the New York-based for-profit charter school management company Mosaica Education. Two years later, that company broke its five-year contract and fled because, according to the emergency manager, “the profit just simply wasn’t there.”

And here’s a grim footnote to this saga: in 2012, in preparation for the new charter school district, cryptically named the Muskegon Heights Public School Academy System, the emergency manager laid off every single school employee.

“We knew it was coming,” explained one of the city’s longtime elementary school teachers. She asked not to be identified, so I’ll call her Susan. “We received letters in the mail.”

Then, around one a.m. the night before the new charter school district was slated to open, she received a voicemail asking if she could teach the following morning. She agreed, arriving at Martin Luther King Elementary School for what would be the worst year in her more than two-decade career.

When we visit that school, a single-story brick building on the east side of town, the glass of the front door had been smashed and the halls were empty, save for two people removing air conditioning units. But in the fall of 2012, when Susan was summoned, Martin Luther King was still filled with students—and chaos. Schedules were in disarray. Student computers were broken. There were supply shortages of just about everything, even rolls of toilet paper. The district’s already barebones special education program had been further gutted. The “new,” non-unionized teaching staff—about 10 percent of whom initially did not have valid teaching certificates—were overwhelmingly young, inexperienced, and white. (Approximately 75 percent of the town’s residents are African American.)

“Everything was about money, I felt, and everyone else felt it, too,” Susan says.

With her salary slashed to less than $30,000, she picked up a second job at a nearby after-school program. Her health faltered. Instructed by the new administration never to sit down during class, a back condition worsened until surgery was required. The stress began to affect her short-term memory. Finally, in the spring, Susan sought medical leave and never came back.

She was part of a mass exodus. Advocates say that more than half the teachers were either fired, quit, or took medical leave before the 2012-2013 school year ended. Mosaica itself wasn’t far behind, breaking its contract at the end of the 2014 school year. The emergency manager said he understood the company’s financial assessment, comparing the school system to “a broke-down car.” That spring, Governor Snyder visited and called the district “a work in progress.”

Across the state, the education trend has been toward privatization and increased control over local districts by the governor’s office, with results that are, to say the least, underwhelming. This spring, a report from The Education Trust, an independent national education nonprofit, warned that the state’s system had gone “from bad to worse.”

“We’re now on track to perform lower than the nation’s lowest-performing states,” the report’s author, Amber Arellano, told the local news.

Later that afternoon, we visited the city’s James Jackson Museum of African American History, where we sat with Dr. James Jackson, a family physician and longtime advocate of community-controlled public education in the city.

He explains that the city’s now-failing struggle for local control and quality education is part of a significantly longer history. Most of the town’s families originally arrived here in the first half of the twentieth century from the Jim Crow South, where public schools for Black students were not only abysmally underfunded, but also thwarted by censorship and outside governance, as historian Carter Goodwin Woodson explained in his groundbreaking 1933 study, The Mis-Education of the Negro. Well into the twentieth century, for example, the Declaration of Independence and the US Constitution were barred from grade-school textbooks for being too aspirational. “When you control a man’s thinking you do not have to worry about his actions,” Woodson wrote back then.

More than eight decades later, Dr. Jackson offered similar thoughts about the Muskegon Heights takeover as he led us through the museum, his bright yellow T-shirt reminding us to “Honor Black History Every Day 24/7—365.”

“We have to control our own education,” Jackson said, as we passed sepia newspaper clippings of civil rights marches and an 1825 bill of sale for Peggy and her son Jonathan, purchased for $371 by James Aiken of Warren County, Georgia. “Until we control our own school system, we can’t be properly educated.”

As we leave, we stop a moment to take in an electronic sign hanging in the museum’s window that, between announcements about upcoming book club meetings and the establishment’s hours, flashed this refrain in red letters:

The education of

Muskegon Heights

Belongs to the People

Not the governor

The following day, we finally arrived back in Detroit, our notebooks and iPhone audio records and camera memory cards filled to the brim, heads spinning from everything we had seen, our aging Prius-turned-tour-bus in serious need of an oil change.

While we had been bumping along on our Magical Michigan Tour, the national landscape had, in some ways, grown even more surreal. Bernie Sanders, the independent socialist senator from Vermont, announced that he was challenging Hillary Clinton for the Democratic ticket. Detroit neuroscientist Dr. Ben Carson—famous for declaring that Obamacare was “the worst thing that has happened in this nation since slavery”—entered the Republican circus. And amid the turmoil, Governor Snyder’s style continued to attract attention, including from the editors of Bloomberg View, who touted his experience with “urban revitalization,” concluding: “His brand of politics deserves a wider audience.”

So buckle your seat belts and watch out. In some “revitalized” Bloombergian future, you, too, could flee your school district like the students and teachers of Muskegon Heights, or drink contaminated water under the mandate of a state-appointed manager like the residents of Flint, or be guaranteed toxic fumes to breathe like the neighbors of 48217, or get shot like Terrance Kellom by federal agents in your own living room. All you have to do is let Rick Snyder’s yellow submarine cruise into your neighborhood.

Laura Gottesdiener is a freelance journalist and the author of A Dream Foreclosed: Black America and the Fight for a Place to Call Home. Her writing has appeared in Mother Jones, Al Jazeera, Guernica, Playboy, Rolling Stone, and frequently at TomDispatch.

Eduardo García is an Ann Arbor-based photographer and researcher focused on indigenous peoples in México, Mexican and Central American migration, disappearances, and social movements in Latin America.

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook. Check out the newest Dispatch Book, Nick Turse’s Tomorrow’s Battlefield: US Proxy Wars and Secret Ops in Africa, and Tom Engelhardt’s latest book, Shadow Government: Surveillance, Secret Wars, and a Global Security State in a Single-Superpower World.