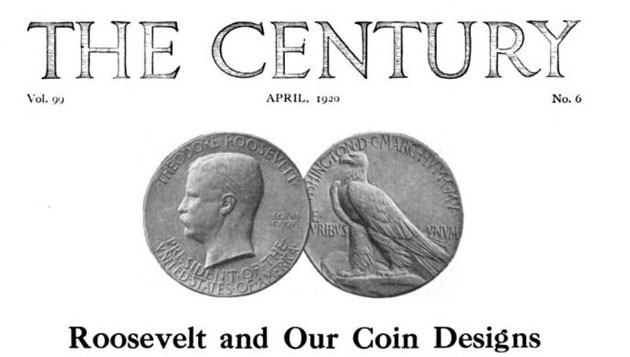

A 1908 "double eagle" gold coin, commissioned by Roosevelt.Wikimedia Commons

After Sunday’s decisive vote to reject a financial bailout offer, Greece may now be inching closer to leaving the eurozone—the collection of 19 countries that maintains the euro. If it does, it will need a new currency, of course, likely the drachma—the name of Greece’s currency going back to ancient times.

Ancient Greek drachma coins, as it happens, were famous for their artistry, especially the handcrafted, high-relief designs—three-dimensional and elaborate—that rose from the faces of the coins. Many coins from Athens featured an owl, the bird representing the goddess Athena, with her face on the flip side of the coin (the owl design was replicated for Greece’s modern-day 1 euro coin). “Ancient Greek coins are undeniably some of the most beautiful coins ever produced in the ancient world,” said Philip Kiernan, a professor of archeology at the University of Buffalo where he studies ancient money, a field known as numismatics. “They’re little miniature works of art.”

The Athenian tetradrachm (worth four drachmas) was probably the most commonly used coin, starting around the 6th century B.C., and lasting until the 2nd century B.C., according to Kiernan. The Romans finally sacked Greece and installed their own currency, but at its peak, “Athens once produced what was essentially the US dollar of the ancient world,” Kiernan said. “They were considered, remarkably, a very stable currency in the ancient world.”

“Would that our coins today were as pretty as that!” he bemoaned when I spoke to him.

In fact, the enduring beauty of the ancient drachma has reached far into the modern world, even captivating, for several intense years, President Theodore Roosevelt.

Roosevelt thought the designs of US coins at the time were lifeless and stale, unbecoming of a great nation. “I think our coinage is artistically of atrocious hideousness,” he wrote to the treasury secretary in 1904. Roosevelt wanted new designs that harked back to the high-relief Hellenic masterpieces but also captured the spirit of a nation growing in stature around the world.

At a White House dinner the following year, an obsessed Roosevelt located his kindred spirit: an Irish-born, New York-raised sculptor named Augustus Saint-Gaudens, who had already designed the president’s inaugural medal and shared the president’s love of drachma coins. Roosevelt—so moved to redesign the country’s currency that he feared the treasury secretary thought him “a crack-brained lunatic on the subject”—commissioned the master sculptor to make designs for a new penny, $10, and $20 coin. “This is my pet crime,” said the president, referring to his passion for the subject.

Saint-Gaudens got to work. “You have hit the nail on the head with regard to the coinage,” he wrote to the president. “Of course the great coins (and you might say the only coins) are the Greek ones you speak of.”

What emerged from his arduous commission, which was plagued by political, bureaucratic, and technological problems, was the famous 1907 $20 gold coin, a.k.a the double eagle, widely regarded as an artistic triumph.

Saint-Gaudens’ Lady Liberty powers toward the viewer of the coin, carrying an olive branch and a torch, with dawn light splintering behind her. The US Capitol building can be seen in the bottom left-hand corner. Law required the artist to use an eagle for the design on the flip side of the corn.

But the coin was hard to make: It took nine strikes from a hydraulic press to fashion each one, making mass production impossible. Fewer than 24 were minted, in February and March 1907, according to the Smithsonian.

“The minting process of the day was not conducive to high-relief coins,” says the US Mint. “As a result, despite being considered one of the most beautiful gold pieces ever minted, Saint-Gaudens’ full vision for the production of an ultra high relief coin was never realized.”

Roosevelt was nonetheless deeply impressed by Saint-Gauden’s work. Writing about the sculptor’s prototypes for a new $10 coin, Roosevelt wrote ecstatically: “Those models are simply immense—if such a slang way of talking is permissible in reference to giving a modern nation one coinage at least which shall be as good as that of the ancient Greeks… it is simply splendid. I suppose I shall be impeached for it in Congress; but I shall regard that as a very cheap payment!”

The sculptor died of cancer in August 1907, amid mounting problems with manufacturing the new coins. His design, though, lasted in some form until 1933, though it was fundamentally altered from his dramatic, high-relief original.

The fascinating, and quite personal, correspondence between Roosevelt and the sculptor was published in April 1920, in the Century, which editorialized enthusiastically about the project:

“The President’s share in the new issue of coins, the thought, the patience, the unflagging enthusiasm, and the insistence that he brought to bear is a vivid example of his high regard for the need of artistic development in our national life.”

In 2002, one of the only 1933 “double eagles” known to have survived sold for more than $7 million at auction.