Supporters rally for victims of police brutality at a Black Lives Matter protest.a katz/Shutterstock

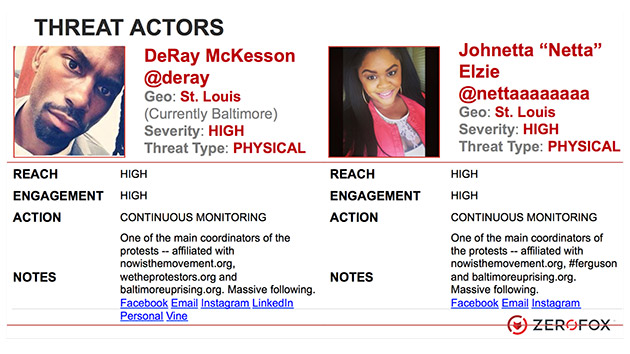

Last Friday, the Intercept released documents revealing that the Department of Homeland Security had been monitoring the Black Lives Matter movement since protests erupted in Ferguson, Missouri, last August. Emails obtained via the Freedom of Information Act showed that the department had tracked the movements of people at a Freddie Gray-related protest in Washington, DC, and had also monitored cultural events like DC’s Annual Funk Parade and prayer vigils in predominately black neighborhoods nationwide. DHS also tracked hashtags and other social media associated with Black Lives Matter.

Nusrat Choudhury, a staff attorney at the American Civil Liberties Union’s Racial Justice Program, says that while this type of surveillance may not be illegal, it may have significant chilling effects that do infringe on people’s rights. “There’s no question at all that the kind of mapping identified by the documents provided to Intercept chills people’s First Amendment-protected activities,” she says. “Of course it makes people feel afraid to go to these kinds of protests because of the impact it might have in terms of law enforcement’s ability to gather intelligence about them.” It may difficult to tell if this has happened, but, Choudhury says, “The line is drawn when that effect takes place.”

Federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies have the legal authority to monitor people and activities in public places. This includes attending, observing, and taking notes on protest activities. However, collecting and storing personally identifiable information on specific individuals is not allowed, with the exception of people suspected of criminal activity. Monitoring tweets and other social media posts, including any geolocation information associated with those posts, is also legal.

Asked for comment, DHS spokesperson S. Y. Lee told Mother Jones that the department’s National Operating Center did monitor Black Lives Matter for “situational awareness purposes” to “ensure that critical information reaches appropriate decision-makers in federal, state, local, tribal and territorial governments.” According to DHS documents, the NOC’s Social Media Monitoring and Situational Awareness program does not collect any personally identifiable information, and surveillance is conducted by searching certain hashtags and keywords on social media sites, not by watching particular personal user accounts.

The ACLU is also concerned that the surveillance of Black Lives Matter could amount to racial profiling. “Because of the predominance of people of color in the Black Lives movement, and the evidence that some of these documents show government surveillance of innocuous cultural events, including music events as well as peaceful protests that take place in historically black neighborhoods, there’s a serious concern that surveillance of Black Lives Matter and cultural events will lead to racial profiling,” Choudhury says. The Department of Justice bans racial profiling by federal law enforcement agencies.

The federal government’s history of surveillance of black civil rights activists in the 1960s and 1970s also adds cause for concern, according to Choudhury. “We have these long-standing concerns that government has engaged in surveillance of people not because there’s evidence of wrongdoing, but because of what they think, what they believe, and what their ideology is, as well as the color of their skin.”

Determining whether the DHS’s monitoring of Black Lives Matter has had a chilling effect on individuals’ First Amendment rights or a disparate impact on African-Americans would require identifying people whose social media posts were monitored and who attended protests that were watched, and ascertaining the effect of the surveillance on them. “But based on the kinds of things that people interviewed by Intercept were saying, there is real concern that the impact is there,” Choudhury says.