Twenty miles outside Salt Lake City, a massive man-made bunker known as The Vault stretches nearly 700 feet into a mountain of granite. Sealed behind colossal doors designed to survive a nuclear attack, the climate-controlled cavern is home to the world’s largest collection of genealogical records—3.5 billion at last count. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has been collecting these records since the late 1800s so its members may identify and posthumously baptize ancestors who might then join them in the afterlife. The public isn’t allowed inside The Vault. But many of its holdings, which include everything from US census records to Jamaican marriage certificates, are available for free on the church’s FamilySearch website, which has information on more than 4 billion people.

Before they can be used to track down long-gone relatives, the church’s records first must be indexed so they’re searchable. Even with thousands of volunteers entering information from scanned documents, the church can’t process the data fast enough. “People come and they go,” says Mike Judson, who’s in charge of recruiting data entry volunteers. “They do a little bit here, a little bit there.” So the church has tapped into a more consistent source of labor: prisoners.

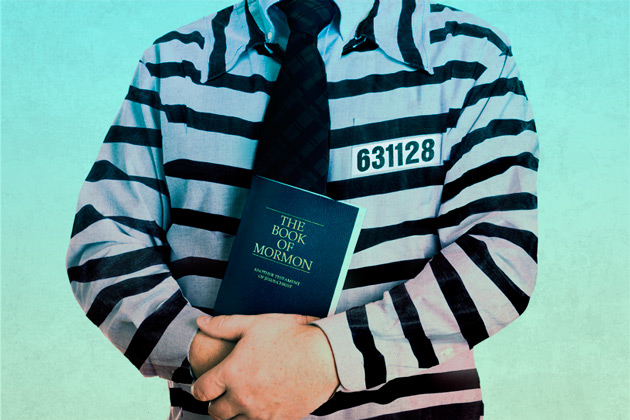

For about a decade, the Mormons have enlisted inmates in two Utah prisons to index records, explains Paul Starkey, the church’s manager of indexing operations. Prisoners who get a job scanning government documents earn between $0.60 and $1.75 an hour. Yet those doing genealogical work for the church are considered volunteers and are not paid a dime.

For Mormon inmates, who make up a third of Utah’s prison population, the Family History Project provides an important link to the church. Church members who are convicted of a crime may be “disfellowshipped” or put on a probationary period during which they must repent or be excommunicated. Volunteering for the genealogy project “would certainly help” prevent excommunication, says Michael Wilder, an ex-Mormon and former High Council member.*

Non-Mormon inmates have more temporal reasons to volunteer in the prison “family history centers.” Greg Johnson, the administrative coordinator of the Utah Parole Board, says the work may be looked at favorably when inmates come up for parole. In addition, Judson says it helps them develop important research skills like paleography, the deciphering of historical handwriting.

Over the past three years, the indexing project has expanded to 32 prisons and jails across Utah, Idaho, and Arizona. In 2013, inmates supervised by missionaries and using church-supplied computers processed around 2 million records. Last year, they logged 7.5 million. The church is currently exploring expanding the program to prisons in California, Florida, Ohio, Oregon, and Washington.

Asked whether non-Mormon inmates were informed that their genealogical work might be used to baptize the dead, Judson replies, “I don’t know what they are told, exactly.” When I tried my hand at indexing documents in the Salt Lake City Family History Center, the volunteers stressed that my efforts would contribute to the publicly accessible FamilySearch database. They were cagey when I asked about posthumous baptism. Originally meant to extend the church’s blessings to church members’ deceased ancestors, the practice has also baptized millions of non-Mormons, including Mahatma Gandhi, Elvis Presley, and Adolf Hitler. In 1995, the church promised to stop the controversial practice of posthumously baptizing Holocaust victims. The church states that the practice is not an imposition since “the validity of a baptism for the dead depends on the deceased person accepting it.”

Judson says that Mormon or no, the main reason inmates sign up to digitize old records is the “good feeling that comes from it.” He also recalls asking an inmate why he participated in the program; the inmate replied, “I would have done anything to get out of my cell.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that the High Council is the church’s governing body. High Councils supervise groups of local congregations, or stakes.