One hot morning in May, Kiana Hernandez came to class early. She stood still outside the door, intensely scanning each face in the morning rush of shoulders, hats, and backpacks. She felt anxious. For more than eight months she had been thinking about what she was about to do, but she didn’t want it to be a big scene.

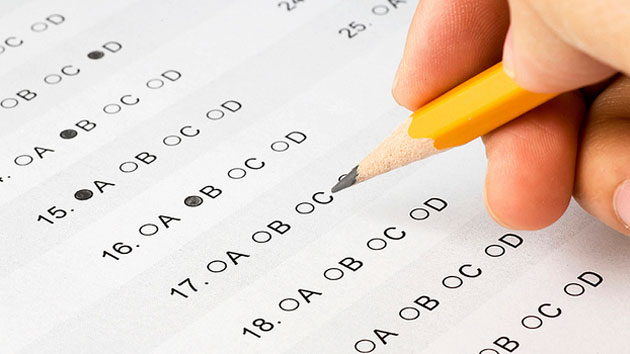

As her English teacher approached the door, she blocked him with her petite, slender frame. Then, in a soft voice, she said, “I’m sorry. I’m not going to take the test today.” The multiple-choice test that morning was one of 15 that year alone, and she’d found out it would be used primarily as part of her teacher’s job evaluation. She’d come into class, she said, but would spend the hour quietly studying.

The teacher stared at her dark-brown eyes in silence while students shuffled past. “That’s a mistake,” he said with a deep sigh.

By her own estimate, Kiana had spent about three months during each of her four years at University High in Orlando preparing for and taking standardized tests that determined everything from her GPA to her school’s fate. “These tests were cutting out class time,” she says. “We would stop whatever we were learning to prepare.” The spring of her senior year, she says, there were three whole months when she couldn’t get access to computers at school (she didn’t have one at home) to do homework or fill out college applications. They were always being used for testing.

Kiana had a 2.99 GPA and is heading to Otterbein University in Ohio this fall. She says she did well in regular classroom assignments and quizzes, but struggled with the standardized tests the district and state demanded. “Once you throw out the word ‘test,’ I freeze,” she tells me. “I get anxiety knowing that the tests count more than classwork or schoolwork. It’s a make or break kind of thing.”

Junior year had been particularly hard. She’d failed the Florida reading test every year since sixth grade and had been placed in remedial classes where she was drilled on basic skills, like reading paragraphs to find the topic sentence and then filling in the right bubbles on a practice test. She didn’t get to read whole books like her peers in the regular class or practice her writing, analysis, and debating—skills she would need for the political science degree she dreamed of, or for the school board candidacy that she envisioned. (Sorting students into remedial classes, educational research shows, actually depresses achievement among African American and Latino students in many cases, yet it remains common practice.)

Kiana was living with her mother, and times were tough. Some days there was no food in the house. “The only thing that kept me going to school was my math teacher,” Kiana says. “The only place that I felt that I had worth was Mr. Katz’s class. That’s the thing that kept me going every day.”

On the news, Kiana saw pictures of students and parents carrying signs reading “Opt-Out: Boycott Standardized Testing.” Her high school didn’t have activists like that. In the library, Kiana made flyers that read: “Are you tired of taking time consuming and pointless tests? Boycott Benchmark Testing! When given the test, open the slip and do NOT pick up your pencil. Refuse to feed the system!” She passed them out to her classmates, but they were worried that opting out would hurt their GPAs.

Kiana talked about this with Mr. Katz, who regularly met with students who needed extra help during his lunch hour and after school. One day during their tutoring session, he mentioned Gandhi. Kiana went to the library and found some of Gandhi’s essays. She determined that what it took to make change was someone taking a personal stand.

Next, she researched state education rules and discovered that the end-of-course tests that Florida required in every subject were being used primarily for job evaluations. (She says one teacher told her: “Please take [the test]. My paycheck depends on it.”)

The English teacher started passing out the computer tablets used to take the test. He put one on her desk. Kiana raised her hand. “I’m sorry,” she said again. “I’m not going to take this test.”

The noise dropped abruptly.

“You should wait until you are done with high school before you try to change the world,” the teacher said.

Kiana reached into her backpack and pulled out a notebook to prepare for her psychology final.

Critics have long warned that a flood of standardized testing is distorting American education. But in recent months, an unprecedented number of students like Kiana, along with teachers and parents across the country, have chosen to take matters into their own hands—by simply refusing to take part.

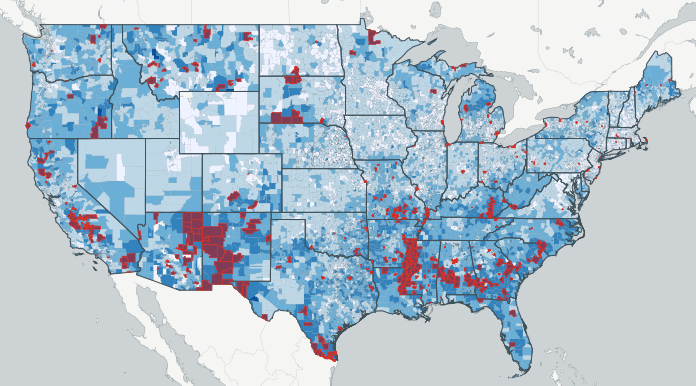

“This school year saw by far some of the largest numbers of families opting out from standardized tests in history,” Bob Schaeffer, director of public education at the advocacy group FairTest.org, told me this spring. In New Jersey, 15 percent of high school students chose not to take state tests in the 2014-15 school year. In New York state, only a few districts reported meeting 95 percent participation, the minimum required by federal rules, according to a New York Times investigation. There are opt-out activists in every state, and in Florida—thanks in part to the hardcore pro-testing policies implemented by former Gov. Jeb Bush—the backlash is especially severe.

“Half the counties in Florida have an opt-out group,” Cindy Hamilton, a parent and cofounder of Opt Out Orlando, told me. She said her group is not against tests per se, but against the process being taken out of the hands of teachers and schools and turned over to outside vendors. (As NPR’s Anya Kamenetz has documented, the testing industry, controlled by a handful of companies such as CBT/McGraw-Hill, Harcourt, and Pearson, has grown from $263 million worth of sales in 1997 to $2 billion.) “Our movement,” Hamilton said, “is civil disobedience against the gathering of all of this data by for-profit companies that doesn’t help students learn.”

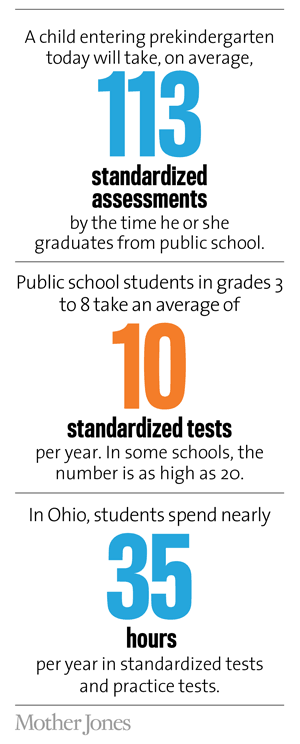

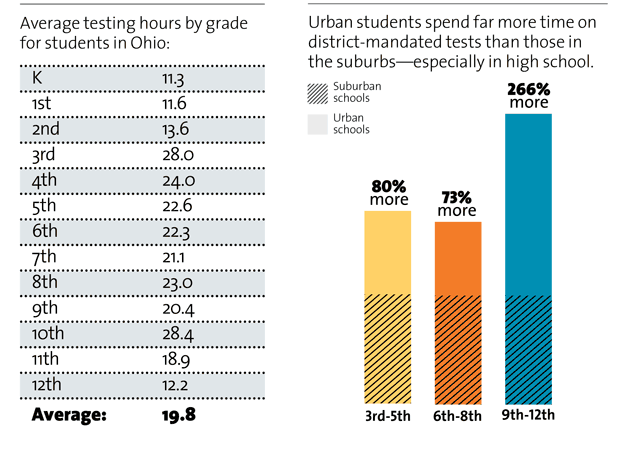

Students in American public schools today take more standardized tests than their peers in any other industrialized country. A 2014 survey of 14 large districts by the Center for American Progress found that third- to eighth-graders take 10 standardized tests each year on average, and some take up to 20. By contrast, students in Europe rarely encounter multiple-choice questions in their national assessments and instead write essays that are graded by trained educators. Students in England, New Zealand, and Singapore are also evaluated through projects like presentations, science investigations, and collaborative assignments, designed to both mimic what professionals do in the real world and provide data on what students are learning.

In the past three years, I interviewed hundreds of students across the nation while reporting my book, Mission High. In schools both urban and suburban, affluent and struggling, students told me that preparing for such tests cut into things that advanced their education—projects, field trips, and electives like music or computer classes.

“Testing felt like such a waste,” Alexia Garcia, a 2013 graduate of Lincoln High in Portland, Oregon, told me. “It felt really irrelevant and disconnected from what we were doing in classes.” As a senior, Garcia became a lead organizer with the Portland Student Union, a coalition with members in 12 area high schools that has been one of the most visible student groups in the national student opt-out movement. Garcia, who is now at Vassar College, told me that this year—thanks to the Black Lives Matter movement—students are also increasingly talking about how standardized testing contributes to inequality and ultimately the “school-to-prison pipeline.”

Joshua Katz, Kiana Hernandez’s math teacher, says he tests his students using a variety of challenges and quizzes, but the only ones that officially count are the fill-in-the-bubble variety. “They tell me I must have data, and they don’t consider tests data unless it comes from multiple-choice,” Katz told me.

Every nine weeks, Katz has to stop whatever his students are doing and make time for the district’s benchmark tests measuring student progress toward the big Common Core exam in the spring. (Proponents of the Common Core standards, now in place in 43 states, promised fewer tests and less of a focus on multiple-choice. But most of the teachers told me there had been no change in the number of standardized assessments. “This year was a circus—16 weeks of testing scheduled at the high school level,” Katz said.)

And University High, whose neighborhood and student population is largely middle class, didn’t bear as heavy a load of tests and drills as its poorer counterparts: One recent study found that urban high school students spend 266 percent more time taking district-level exams than their suburban counterparts. That’s in part because the stakes for these schools are so high: Test scores determine not just how much funding a school will get, but whether it will be allowed to stay open at all. In response, some administrators have been taking desperate measures, including pushing the lowest-performing students out entirely. Suspensions have been growing across the country, especially among African American and Latino students, and many researchers correlate this with pressure to raise scores. And in the 2011-12 school year, the Government Accountability Office reported that officials in 33 states confirmed at least one instance of school staff flat-out cheating.

With so much controversy revolving around the effect of testing on struggling students and schools, it’s hard to remember that the movement’s original goal was to level the educational playing field. In 1965, as part of the War on Poverty, the Johnson administration sent extra federal funding to low-income schools, and in return asked for data to make sure the money was making an impact. As more states started using standardized tests in the 1970s and 1980s, urban education researchers were able to identify which schools were helping students of color and those from poor families achieve—giving the lie to the idea that these students couldn’t succeed.

By the late ’80s, many educators were pushing to deploy reliable, external data to measure student progress, a movement that culminated in the bipartisan support for President George W. Bush’s No Child Left Behind initiative. With NCLB, states were required to gather and analyze vast amounts of testing data by race, ethnicity, and class. Researchers soon started mining this information, convinced that they could reveal what really worked in education. One 2006 study found that putting students in a top-rated teacher’s class raised average scores by 5 percentage points. Another connected increases in test scores to higher earning levels, lower pregnancy rates, and higher college acceptance rates.

Findings like this encouraged two major beliefs in policy circles: First, that test scores were a key factor in how students would do later in life. And second, that the best way to improve teaching was to reward the top performers and fire the bottom ones, based in large part on their students’ scores. High-profile charter schools like KIPP and Uncommon Schools, whose model relied in part on avoiding teacher tenure, helped cement that belief.

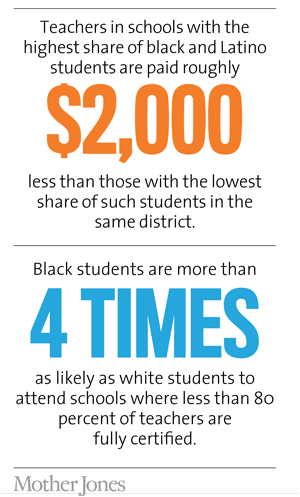

By 2009, President Barack Obama used his Race to the Top initiative to promote using test scores to hire, fire, and compensate teachers. Today, 35 states require teacher evaluations to include these scores as a factor—and many states have introduced new tests just for this purpose. Until this year, Florida used end-of-course tests in virtually every subject to give bonuses to some teachers and punish others. When Kiana’s math teacher, Joshua Katz, was downgraded to “effective” from “highly effective” this year, his salary was slated to drop by $1,100.

But while using student test scores to rate teachers may seem intuitive, researchers say it actually flies in the face of the evidence: Decades of data indicates that better results come not from hiring innately better teachers, but from helping them improve through constant training and feedback. Perhaps that’s why no other nation in the world uses annual, standardized tests to set teacher salaries. (Other countries use test scores to push teachers to improve, but not to punish them.)

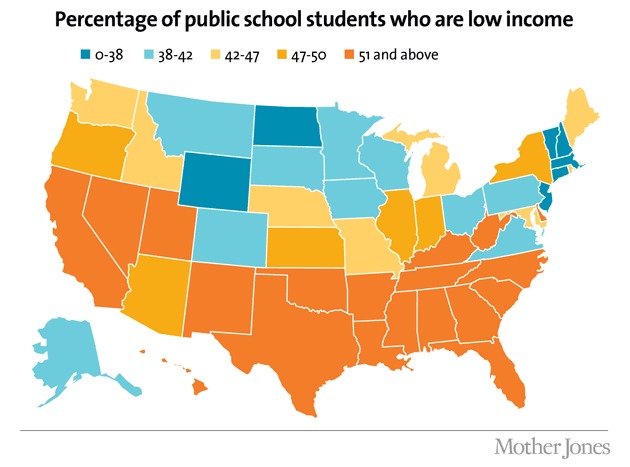

Nor do other developed nations have such a drastic gap in funding between rich and poor schools. Mission High School in San Francisco, for example, spends $9,780 per student, while schools in Palo Alto, just 30 miles away, spend $14,995. New York spends $19,818 per student, California just $9,220. The per student funding gap between rich and poor schools nationwide has grown 44 percent in the last decade—even as the number of needy students has grown. In 2013, for the first time in at least 50 years, a majority of US public school students came from low-income families.

All this presents a significant risk for a country that has relied on schools as the primary avenue for social mobility. Prudence L. Carter, a professor in the school of education at Stanford University, says in fact, kids have very different opportunities: Affluent students ride through the education system in what amounts to a high-speed elevator supported by well-paid teachers, intellectually challenging classes, and private tutors. Middle-class kids are on an escalator. Their parents may struggle to keep up, but still can access resources to help their children prepare for college. And then there are low-income students like Kiana, who are left running up a staircase with missing steps and no handrails.

When it comes to standardized testing, this means that schools that educate low-income students start out at a disadvantage: They are much more likely to have lower-paid and less-qualified teachers; lack college preparatory classes, books, and supplies; and offer fewer arts and sports programs. When their students don’t make it to the same “proficiency” benchmarks on yearly tests as their wealthier counterparts, politicians label them and their teachers as “failing.” And that begins a vicious cycle: Struggling students are pushed into remedial classes that zero in on what’s measured on the tests, further limiting their opportunities to learn the advanced skills they’ll need in college or the workplace.

“What I observed was egregious,” Ceresta Smith, a 26-year veteran teacher in Miami and a cofounder of United Opt Out National, told me about a predominantly African American, low-income school where she worked from 2008 to 2010. Some teachers tried to incorporate writing and intellectually engaging readings, she said, but most resorted to remediation of basic skills. “Students are reading random passages and practice picking the correct multiple-choice. It was very separate and unequal.”

The proponents of testing-based reform like to argue that—while imperfect—the current approach has been working better than any other, leading to rising graduation rates and standardized test scores. But as Stanford researcher Linda Darling-Hammond has pointed out, there’s a bit of circular logic at work here: A system singularly focused on producing better test scores leads to…better test scores. Meanwhile, though, American students’ performance compared to other nations—on tests that measure skills and knowledge more broadly—remained flat or declined between 2000 and 2012.

Most importantly, test-based accountability is failing on its most important mandate—eliminating the achievement gap between different groups of students. While racial gaps have narrowed slightly since 2001, they remain stubbornly large. The gaps in math and reading for African American and Latino students shrank far more dramatically before No Child Left Behind—when policies focused on equalizing funding and school integration, rather than on test scores. In the 1970s and ’80s, the achievement gap between black and white 13-year-olds was cut roughly in half nationwide. In the mid-’70s, the rates at which white, black, and Latino graduates attended college reached parity for the first and only time.

In the decades since, the encouraging news is that the black-white achievement gap has kept slowly shrinking. But at the same time, the gap between students from poor and affluent families has widened into a chasm, growing by 40 percent between 1985 and 2001. Sean Reardon, a Stanford professor who focuses on poverty and inequality in education, says this is not surprising—affluent families can spend more than ever on enrichment activities. He argues it’s up to government to level the playing field, by making sure low-income students get the opportunity to succeed. But in many places, government is instead pulling back from the civil rights era’s focus on educational inequality.

Today, many students of color are once again going to segregated, high-poverty schools that struggle to offer advanced classes and attract teachers and counselors. Some 40 percent of black and Latino students now are in schools at which 90 to 100 percent of the student body are kids of color.

To be sure, the test-based reform movement still has powerful proponents—politicians like Jeb Bush and Secretary of Education Arne Duncan, philanthropists like Bill Gates, some teachers, and prominent civil rights organizations such as the NAACP and National Council of La Raza. “For the civil rights community, data provide the power to advocate for greater equality under the law,” a coalition of 12 groups argued in a recent joint statement criticizing the opt-out movement. “We cannot fix what we cannot measure.” Some teachers I spoke to echoed that message: Lauren Fine, an elementary-school teacher in Denver, believes that without the standards and annual assessments, we won’t be able to maintain “a high bar for every student.” President Barack Obama agrees with this line of reasoning and recently said that as Congress debates rewriting the No Child Left Behind law, he won’t sign any bills that don’t include requirements for annual testing, accountability, and state interventions.

But a growing list of others, from the students and parents in the opt-out movement to youth and labor groups and education researchers, are arguing that the push for standardized testing has in fact exacerbated inequities. Journey for Justice is a coalition of grassroots youth and parent groups in 21 cities. “Our concern is that the people who are most directly impacted by these education policies are never consulted,” director Jitu Brown told me.

Brown, who saw firsthand the impact of the recent closures of 50 low-scoring schools in his native Chicago, says politicians should look at the real world rather than listening to “education entrepreneurs who are implementing mediocre interventions in our communities.” In Chicago, he notes, “you had young people being displaced as the one stable institution in our community was eliminated. You had the massive firing of black teachers, as if they were the problem—when equity never existed.”

So assume for a moment that the opt-outers succeed: We’d still need ways to improve teaching, assess what students are learning, and reduce the achievement gaps. How should that happen instead?

I found some answers as I spent two years in classrooms with Pirette McKamey, a highly respected teacher at Mission High, and Ajanee Greene, a bright, resilient senior who had just finished a powerful 10-page research paper—even though, as a freshman, she got a D in English at her old school. As I watched McKamey and her colleagues design lesson plans and pore over Ajanee’s writing together, I realized that a focus on accountability doesn’t have to sacrifice teachers’ growth or students’ love of learning.

One winter morning in 2013, McKamey and seven other teachers sat in an empty classroom at Mission High. A light February rain drummed against the windows as Shideh Etaat passed around roasted almonds and talked about her weekend plans. The teachers had convened for one of their three weekly planning hours. This one was dedicated to in-depth case studies of individual students’ math worksheets, essay drafts, and written notes for science lab investigations.

Etaat, a first-year English teacher, had brought in a poem written by a junior named Jay, who came to California from Thailand two years ago. “Jay is that student who will say, ‘Oh, I don’t write poetry. I’m not creative,'” Etaat said. “But I find that English learners are able to see outside of the box. They have an ability to play with language in this really creative way.”

Etaat explained that she’d given her students photos of five different pairs of shoes. She’d asked them to pick a pair they would not wear, and to create a character to go with them. She passed out the “scaffolding” documentation for her lesson—directions for how to develop a character, some sample stanzas, a poem she had written herself based on the assignment. Educational theorists call this teaching in the “zone of proximal development“: that place where we can’t progress by ourselves, but we can with targeted assistance and constructive feedback.

The wind whistled through the old window frames as the teachers read Jay’s poem.

My shoes look like a pair of cheap running shoes

Full of sweat and heat

In his shoes, he works hard every day

He sees himself working in the mud

And sleeping on the street with other hobos

In my shoes, I see a student running in the hallway

Trying to get his lunch as early as possible

In his shoes, he hears the heavy metal noise of his hammer

Striking at that thick jet black rock until it resolves

In my shoes, I hear the noisy noise coming out of the classroom

The sound of electronic devices and ceaseless hip hop music

In his shoes, he feels pain coming from his body,

The pain of loneliness and betrayal.

“It’s very hard to scaffold creativity just right,” said Dayna Soares, a second-year math teacher. “Sometimes teachers give you a blank paper and that’s too much freedom. I’m always struggling with this—how can I give my students just enough structure, but in a way that doesn’t make them fill in the blanks?”

They talked about the craft of grading and commenting on student work. When teachers provide feedback on writing, research shows, many default to a “what’s wrong with this paper” strategy, instead of writing responses that promote growth. “Every time a student does an assignment, they are communicating something about their thinking,” McKamey told the group. “And even if it’s far away from what I thought they’d do, they are still communicating the ways they are putting the pieces together. There are so many opportunities to miss certain students and not see them, not hear them, shut them down. It takes a lot of skill, experience, and patience not to do that.” Looking over multiple-choice questions doesn’t help teachers detect these signals, McKamey told me, because they won’t tell you where and why someone got stuck.

In other words: It’s not just students who miss out on a chance to learn when standardized tests set the pace. Teachers, too, lose opportunities to improve their craft and professional judgment—for example, detecting where their students’ thinking hits what McKamey calls a “knot” and figuring out how they can improve. That’s when many fall back on the only available option: repetitive instruction, more testing, and remediation.

What’s essential for teachers to grow, McKamey told me, is collaboration with fellow professionals—and that mutual accountability, she said, is more effective than test scores or even financial bonuses. “What teachers care about,” she said, “is the feedback they get from students, parents, and peers they respect.”

Max Anders, a first-year English teacher, told me that working with McKamey helped him learn how to teach every student individually. “My understanding before was you give work for the middle,” explained Anders, who was teaching Plato’s “The Allegory of the Cave” at the time. “But the best approach is to give rigorous work that challenges everyone and learn how to break it up and scaffold it just right.”

McKamey’s small, sunlit office is lined with binders filled with the lesson plans she has built up over the last 27 years of teaching, including one for Tim O’Brien’s Vietnam War memoir, The Things They Carried. Every year she teaches the novel, McKamey adds material to the binder, because she learns new things from her students and colleagues each time. Underneath her heavy desk, three pairs of shoes sit neatly lined up: black loafers and Mary Janes for teaching and coaching, light-gray sneakers for dance class after school.

I talked to Ajanee Greene in that office one afternoon. Independent and astute, Ajanee wrote the strongest research papers in the English classes I’d been observing. She was about to become the first in her family to graduate from high school and had started filling out college applications.

From the moment she stepped into McKamey’s classroom, Ajanee told me, she started to feel like an intelligent person. “By middle school, I could tell which teacher is looking at my grades and test scores and is just teaching me basics without opportunities to challenge myself. Just because I struggle with some grammar rules doesn’t mean I can’t think deeply. Ms. McKamey believed in me and then pushed me to work really, really hard.”

Ajanee and McKamey had just finished their lunch meeting, an occasional check-in to talk about life and school. As McKamey left for a meeting, Ajanee told me that she’d chosen the topic for her paper—titled “Black on Black Violence: Why We Do This to Ourselves”—because she’d lost her stepfather and several close friends to gun violence.

For the paper, Ajanee had read and analyzed about 20 articles and studies and, with McKamey’s encouragement, had interviewed her neighbors and added her own point of view. She didn’t like how the local paper described her stepfather as a “flashy” man who had recently purchased a piece of new jewelry—implying, it seemed to her, that greed might have been the reason he’d been shot.

Ajanee wanted her readers to understand that her stepdad was a dedicated father of four who was home with his seven-year-old nephew when he was killed. The violence didn’t just affect the victims; it scarred the survivors, Ajanee wrote. “Personal, private, solitary pain is more terrifying than what anyone can inflict. The violence stays with families and becomes a part of their lives. Nobody feels the same and family relationships get strained.” She also added a section on the history of slavery and Jim Crow, writing, “The epidemic of African Americans killing each other didn’t start because we just hate each other. It started when we began to believe the things other races said about us and began to hate ourselves.”

“When you go to school, you learn about math and reading, but you rarely learn new ways of looking and thinking about life,” Ajanee explained. “Learning the skills to research and write this paper helped me learn so much: how many people are dying, why they are dying, how to tell the stories of others and learn about the world. It gave me a better understanding.”

She got an A- for the paper. “When they told me the grade, I thought it must have been a mistake,” she says—she’d read her classmates’ drafts and didn’t think hers measured up. “Before this, the longest paper I wrote was three pages. Now, if I have to write 15 pages in college next year, I feel ready,” she told me. (That was in 2013. This year, after two years in community college, Ajanee transferred to Jackson State University in Mississippi.)

But as politicians, economists, and philanthropists focus on ever more sophisticated number crunching, opportunities for teachers to nurture students’ intellect the way McKamey does have grown more limited. Mission High teachers never complained to me about being overworked, but they worked more hours than anyone I met in the corporate world. For more than a decade, McKamey woke up at 5 a.m., got to school by 6:30, left for dance class at 4:30 p.m., and then worked almost every evening and every Sunday. Most teachers I met worked with students after school and colleagues on weekends, without pay.

And yet the story of Mission High holds out hope for a different kind of school reform—one that builds on resources that already exist in thousands of schools and doesn’t require spending a dime on the next generation of tests, software, or teacher evaluation forms. That’s because Mission has already been through exactly the kind of harsh treatment for “failing” schools that the standardized-testing movement supports—and then it found another way.

In the mid-1990s, Mission had rock-bottom test scores and was targeted by the district for “reconstitution.” The principal was removed and half the teachers were reassigned. Yet in 2001, the school once again had some of the lowest test scores and attendance rates among all of San Francisco’s high schools, and more teachers were leaving it than almost any other school in the district.

Then Mission High tried something new. Instead of bringing in consultants, it mobilized a small group of teachers—including McKamey—to lead reforms on their own. It increased paid time for them to plan lessons together, design assessments, and analyze outcomes. The teachers made videos of students talking about what kind of instruction helped them succeed. They read research about how integrated classes, personalized teaching, and culturally relevant curriculum increased achievement. They asked successful teachers to coach colleagues who needed help.

To focus their efforts and keep each other accountable, McKamey and her colleagues regularly pore over data, both qualitative and quantitative. They look at achievement gaps, attendance, referrals, graduation rates, and test scores. They also walk through classrooms, delve into student work, and interview teachers and students. “We are always looking at and trying to understand different kinds of data, including anecdotal,” McKamey told me. “Then we can settle on something we need to concentrate on each year.” One year, social studies teachers discovered that too many students didn’t fully grasp the difference between summarizing a text versus analyzing it, so they spent the next year building more opportunities to practice those skills. The math department, meanwhile, focused on one-on-one coaching to help set up effective group work.

By contrast, back in Florida, Katz told me that the typical way he receives professional development entails an observation of a model lesson by a district consultant demonstrating how to teach Common Core standards. While University High struggles to keep teachers, Mission High has very low attrition. It is no longer considered a “hard-to-staff” school by the district. “Mission High is famous at the district because it is known as a learning community and a good, supportive place to work,” Soares told me. “It’s hard to get a job here.”

The school does well on a bevy of other metrics, as well. The graduation rate went from among the lowest in the district, at 60 percent, to 82 percent; the graduation rate for African American students was 20 percent higher than the district average that year. Even though close to 40 percent of students are English learners and 75 percent are poor, college enrollment rose from 55 percent in 2007 to 74 percent by 2013. Suspensions plummeted, and in the annual student and parent satisfaction survey from 2013, close to 90 percent said they liked the school and would recommend it to others.

That doesn’t mean there aren’t challenges. Standardized test scores went up 86 points, to 641 (out of 1,000) in 2012, but that was still far from California’s target for all schools of 800. The numbers of African American and Latino students in AP math and science classes don’t fully mirror the student body, and their passing rates on the California high school exit exam went down in 2013 and 2014. The work continues, but so does the commitment of teachers to keep at it. “No one here does 7:45 to 3:10 and then calls it quits,” science teacher Becky Fulop, who has worked at Mission High for more than a decade, told me. “That by itself doesn’t necessarily make teachers effective, but the dedication here is extraordinarily high.”

Nationally, there are thousands of struggling schools like Mission where teachers are engaged in similar hard, messy, and slow work. What if instead of spending more money on new rounds of tests, we focused on their ability to learn and lead on the job?

No country has ever turned around its educational achievement by increasing standardized tests, according to research conducted by Lant Pritchett at the Center for Global Development. The best systems, it turns out, invest in supporting accountability at the school level—like those teacher meetings at Mission High.

“It’s always an attempt to hijack the effort by the teacher to think about education,” McKamey told me one morning as we talked about the dozens of reform efforts she’s seen come and go in 27 years of working in inner-city schools. The only thing none of the politicians, consultants, and philanthropists who came in to fix education ever tried, she said, was a systemic commitment to support teachers as leaders in closing the achievement gap, one classroom at a time.

“Let me remind you what analysis is,” she said a few hours later, standing in the middle of her class with those black leather loafers from under her desk. “When I was little, I used a hammer and screwdriver to crack a golf ball open. As I cracked that glossy plastic open, I saw rubber bands. And I went, ‘Ha! I didn’t know there were rubber bands in golf balls. I wonder what’s inside other balls?’ It made me curious about the world. So we are doing the same thing. We’ll analyze the author’s words to dig in deeper.”

The 25 seniors had just finished reading a chapter from The Things They Carried titled “The Man I Killed.” When they were done, McKamey asked them to pick out a quote they found intriguing.

David, a shy, reflective teenager whose face lit up when the class read poetry, raised his hand:

“He was a slim, dead, almost dainty young man of about twenty. He lay with one leg bent beneath him, his jaw in his throat, his face neither expressive nor inexpressive. One eye was shut. The other was a star-shaped hole.”

“What do you notice in this passage?” McKamey probed.

“The man the narrator killed is the same age as him,” Roberto commented.

“Exactly,” she replied. “Now you are one step deeper. What do I feel inside when I think of that?”

“Guilt, regret,” Ajanee jumped in.

“That’s right,” McKamey commented. “I personally would use the word compassion. But what you said is 100 percent correct. And what does that do when we realize that this man is the same age as us?”

“It makes me think that he’s young, likes girls, probably doesn’t want to fight in a war,” Roberto said.

“Exactly. Now take that even deeper.”

“It’s like he is killing himself?” Roberto said more hesitantly, glancing at her for affirmation.

“Perfect! Now you made a connection,” McKamey said, excitement in her voice. “That’s what this quote is really about. Now, why is O’Brien saying ‘star-shaped hole’? Why not ‘peanut-shaped’ hole?”

Ajanee raised her hand. “The image in his mind is burned.”

“Exactly!” McKamey replied. “O’Brien wants us to keep that same image in mind that he had as a young soldier in his mind. It’s the kind of image you never forget.”