<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/gallery-587791p1.html">haru</a>/Shutterstock

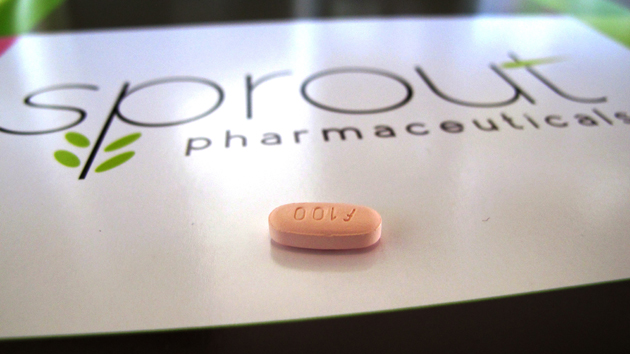

When news broke on August 18 that the Food and Drug Administration approved Addyi, the pill that is being incorrectly referred to as the “female Viagra,” it might have seemed like an obvious feminist win. Viagra has been around since 1998, but there hasn’t been anything remotely comparable on the market for women. Addyi is supposed to alleviate female hypoactive sexual desire disorder (or lack of sexual desire). But as we’ve reported, women on Addyi experienced an increase of only one sexual event per month during clinical trials.

So what’s really going on with the little pink pill? And what’s the latest science on low libidos? We asked Rachel Hills, author of the The Sex Myth, and Emily Nagoski, sex educator and author of Come As You Are, to weigh in:

What is female sexual dysfunction? Hills points out that when Viagra went on the market, it aimed to treat a very specific disease: erectile dysfunction. Viagra works by increasing blood flow to the penis to get an erection hard enough for sex; it does not cause arousal. Addyi targets the brain, and it does aim to increase arousal by stimulating the brain in a way that’s comparable to antidepressants. Hills says this is where it gets tricky, because “female sexual dysfunction” is not well-defined medically, and she thinks the term is being used too broadly. “It’s more amorphous than erectile dysfunction because the ‘disease’ is basically not wanting to have sex enough,” she says.

Do we need Addyi? According to Nagoski, there are two types of desire: spontaneous desire, which occurs without any physical prompting from a partner, and responsive desire, which comes from being in a sexual situation (think foreplay or dirty talk). Nagoski says it’s pretty normal for women to only experience responsive desire. But, maybe because men’s bodies work a little differently, women are led to believe that something is wrong with them if they don’t crave sex every day. Nagoski, who has worked as a sex educator for almost a decade, often hears women say, “Once [my partner and I] got started, everything was fine. It’s getting me started that’s the problem.” She thinks a lot of the hype surrounding Addyi is due to a lack of readily available information surrounding female sexuality.

Is this simply a pharmaceutical company trying to tap into a profitable market? A lot of the hype surrounding Addyi stemmed from good marketing, not a scientific breakthrough. “The most generous possible interpretation of the FDA responder analysis is that, of the thousands of women who were on the drug, a few experienced minimal benefit,” says Nagoski. Hills is also suspicious of the motives behind treating female sexual desire with a pill: “The entire question of female sexual dysfunction was motivated by the fact that there’s potentially a lot of money to be made in that.” There is certainly a lot of money at stake—Sprout Pharmaceuticals, the makers of Addyi, announced that Valeant Pharmaceuticals International acquired the pill for $1 billion.

Let’s talk about pleasure. Nagoski says the problem with Addyi is that it’s purpose is to create desire, but the point of desire falls flat if women aren’t experiencing pleasure. Hills and Nagoski believe the conversation about Addyi is too focused on how much sex women are having, regardless of whether the sex is good or not. For this reason, Hills says she doesn’t buy that Addyi is a feminist victory. “It’s certainly not that I think women should not have the right to sexual desire; it’s just that I think everyone has the right to desire as much sex as they want,” Hills says. “I worry about the desire for sex becoming an imperative.” Nagoski adds that framing a lack of desire as a medical problem reinforces the idea that there’s something wrong, which creates additional pressure that can impede libido. A focus on pleasure rather than desire could break that cycle.

So what’s the key to female sexual arousal? Nagoski details an interesting theory about this in Come As You Are. The way she sees it, the brain has what’s called a “dual-control model,” in which there is a sexual “accelerator” and a sexual “brake.” For the most part, men have more sensitive accelerators and women have more sensitive brakes—it’s easier for them to lose sexual arousal. The key is figuring out what’s hitting the brakes. Nagoski says it could be as simple as being distracted by grit on the sheets, or being worried someone will walk in. Or maybe it’s literally cold feet—a study by Dutch scientists found that wearing socks increased a woman’s chance of having an orgasm. Of course, if the sensitivity is trauma-related, Nagoski says seeing a sex therapist might be the best way to go. But for others, try to “take control of the issues you can take control of,” she says.