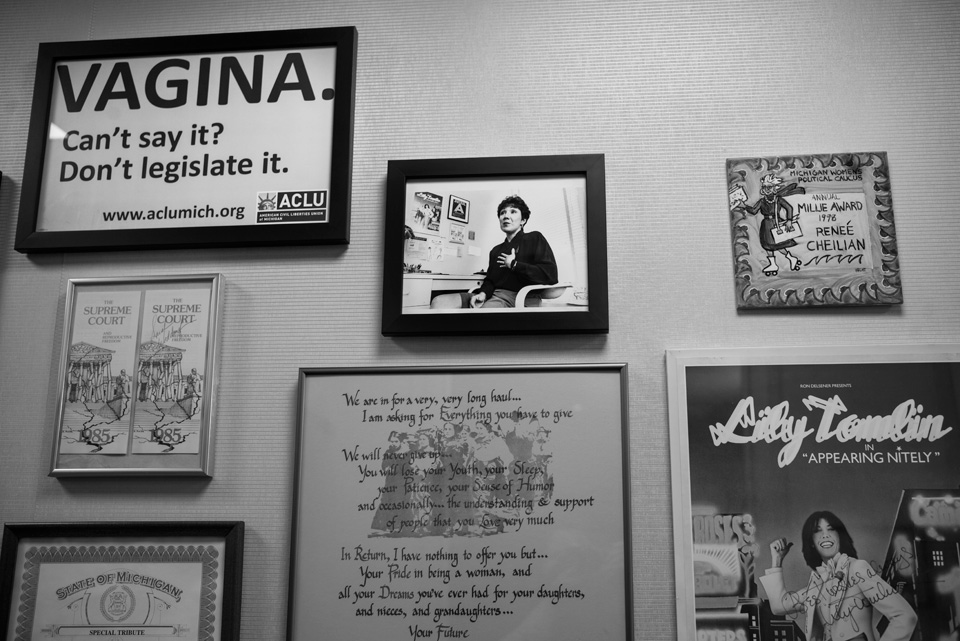

When she was 20 years old, Renee Chelian began every Friday with a predawn drive to an airplane hangar outside Detroit. There she met an abortion doctor, and a pilot who flew them to Buffalo, New York.

This was 1971. Roe v. Wade, the Supreme Court decision that established a woman’s right to an abortion, was still a year and a half away, and New York was one of the few places in the country where abortion was legal. Chelian was the doctor’s assistant. She cleaned instruments and made appointments for women who hitchhiked or drove from all over the Midwest and New England to reach the clinic.

Chelian knew well why these women were willing to make the journey to Buffalo. Just five years earlier, at 15, she’d gotten pregnant by her high school boyfriend. She was resigned to dropping out of school. On the night she was packing her suitcase, “to go get married,” her parents came into her room and asked if she wanted an abortion instead. “What’s that?” Chelian asked.

A few days later, Chelian and her father let a stranger blindfold them and drive them to a warehouse on what she thought were the outskirts of Detroit. Chelian waited her turn on a folding chair, staring at an oil slick on the cement floor. The place seemed to be packed with other women, but it was hard to tell. “All I can picture are women’s feet,” she recalls. “I was afraid to look at anybody, because what if I just somehow upset the balance and they wouldn’t do my abortion?” After what felt like hours, someone—she doesn’t know if he was a doctor—performed the illegal procedure. They packed her with gauze and sent her home.

It wasn’t until years later, when she was working for her family doctor, that she realized how lucky she was not to have been caught, or suffered complications, or died. When the doctor began providing legal abortions in Buffalo, she leaped at the chance to help.

Chelian is now 64 and has two grown daughters. She’s the founder and CEO of Northland Family Planning Center, a group of three clinics that perform abortions in the Detroit suburbs. A petite woman with a blunt haircut and a round face, Chelian is matter-of-fact and seemingly unflappable. But when we talk about her clinics, her tone intensifies. Her business is under constant threat of closure from the conservative Michigan Legislature, which has spent the past four years churning out a string of arbitrary new abortion restrictions designed to shut clinics like Northland down. One proposal required Northland to have one bathroom for every six patients.

“Sometimes, I feel like I’ve gone back 40-some years,” she says. “And I can hardly believe that.” Women trek hundreds of miles north from Dayton, Ohio, or east from South Bend, Indiana, for an abortion at one of her centers. Some are already miscarrying—probably after taking pills or herbal concoctions they got from the internet. A few have tried to open their cervix by digging into it with a sharp object.

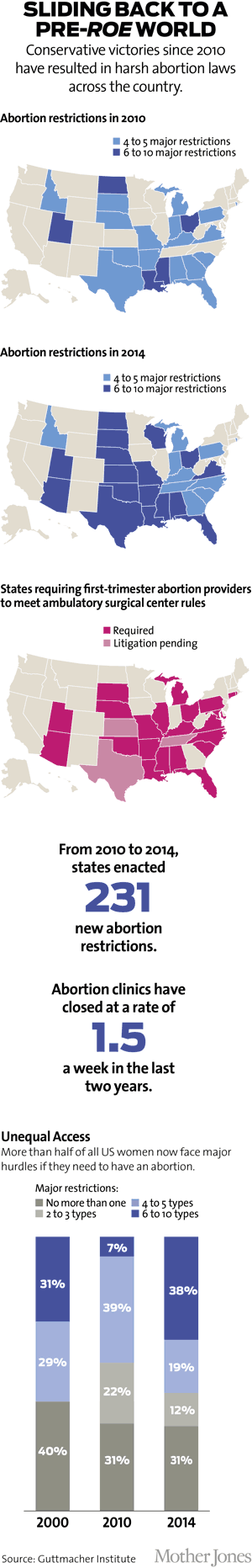

This is what 2015 looks like: Abortion providers struggle against overwhelming odds to stay open, while women “turn themselves into pretzels” to get to them, as one researcher put it. Activists have been calling it the “war on women.” But the onslaught of new abortion restrictions has been so successful, so strategically designed, and so well coordinated that the war in many places has essentially been lost.

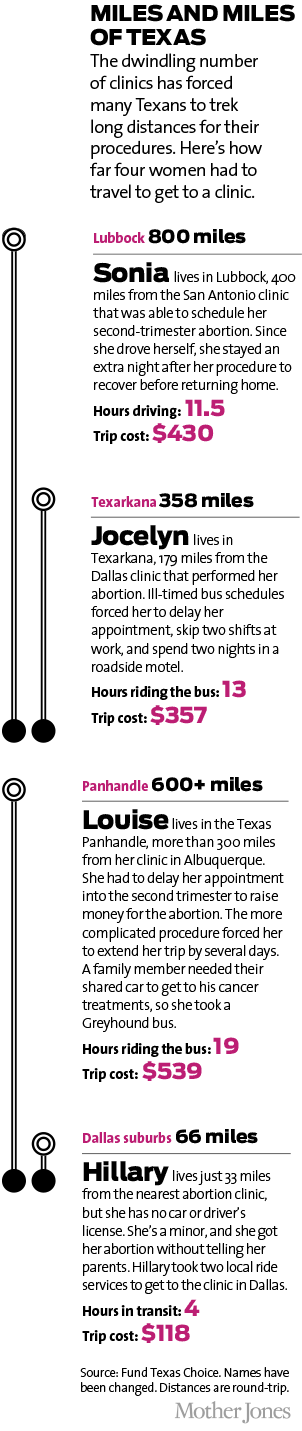

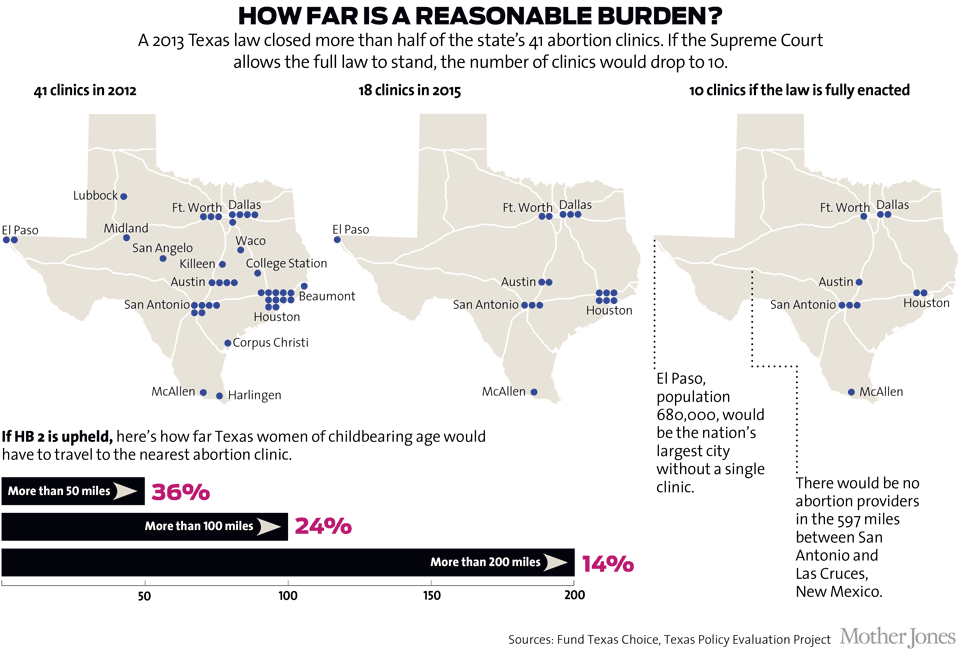

Most abortions today involve some combination of endless wait, interminable journey, military-level coordination, and lots of money. Roe v. Wade was supposed to put an end to women crossing state lines for their abortions. But while reporting this story, I learned of women who drove from Kentucky to New Jersey, or flew from Texas to Washington, DC, because it was the only way they could have the procedure. Even where laws can’t quite make it impossible for abortion clinics to stay open—they are closing down at a rate of 1.5 every single week—they can make it exhausting to operate one. In every corner of America, four years of unrelenting assaults on reproductive rights have transformed all facets of giving an abortion or getting one—possibly for good.

“Every day is just frightening,” Chelian said. “I think things are bad, and then they get worse somewhere else. And you go, ‘Oh my God, it could be worse.’ And I go to sleep with that. I wake up with that.”

About two years ago, Amy Hagstrom Miller, the CEO of Whole Woman’s Health, decided that the best way to provide abortions in Texas was to leave Texas.

It was the summer of 2013. A state senator sporting pink running shoes had just spent 11 hours on her feet filibustering a bill that threatened to shut down more than three-quarters of Texas’ 41 abortion clinics. The night ended with Wendy Davis becoming an internet sensation. But by dawn the next morning, Republican Gov. Rick Perry had announced he’d call the Legislature back for a special session. The bill soon passed.

One portion of the bill—known as HB 2—required all abortions to take place in what amounts to a mini-hospital. Another section required clinics to make administrative pacts with local ERs, which wiped out clinics in areas where all the hospitals are Baptist or Catholic, or susceptible to political pressure.

Before the measure, Texas had 41 clinics. Within four months, there were only 22; today, there are 18. As different sections of the law clicked into place, every clinic west of San Antonio closed down but one—there used to be five—leaving a swath of Texas 550 miles wide without a single abortion provider.

HB 2 was not the only assault on providers. In College Station, the site of Texas’ largest university, a Planned Parenthood clinic, felled by dramatic cuts to the state’s family planning budget, has been replaced by a crisis pregnancy center, a pro-life clinic where women are told scientifically debunked claims about supposed links between abortion and breast cancer or thoughts of suicide.

The new laws have been so confusing that women seeking an abortion in Texas aren’t sure they’re available at all. If you call the Texas Equal Access (TEA) Fund, an organization that helps North Texas women cover the cost of abortions, you’ll hear a voicemail greeting that begins: “We would like to assure you that abortion is still legal in Texas. It is not illegal to seek abortion services.”

Whole Woman’s Health operates four clinics in Texas. But if HB 2 is fully enforced, which means that abortions could only take place in hospital-like clinics, just one of those clinics would remain open. Miller wasn’t willing to concede the fight. Instead, Whole Woman’s Health sued the state, claiming that the distances women would be forced to travel constitute an “undue burden”—the legal standard the Supreme Court established in 1992 for striking down an abortion restriction.

Miller won in district court, but lost when the state took the case to the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals. In June, the US Supreme Court put the 5th Circuit’s decision on hold—for the time being, all 18 clinics remain open pending the high court’s decision in the fall as to whether it will hear the case. Because the lawsuit offers the court a chance to clarify the definition of “undue burden,” it could be the most important—or detrimental—decision on abortion rights in two decades. If Miller loses, Texas will be free to shut down all but 10 clinics.

Miller is not waiting for that. Her newest clinic for Texas women is across the state border—in Las Cruces, New Mexico.

Miller is feisty, with a sharp blond bob and commanding, sonorous voice—think of an energized Patricia Arquette. She operates a total of eight clinics in Texas, New Mexico, Illinois, Maryland, and Minnesota. I met her at the Whole Woman’s Health clinic in Baltimore to talk about the situation in Texas. (“We might as well be in Sweden,” she said, “talking about abortion in Nicaragua.”) One of the central tenets of the abortion rights movement is that no woman should have to cross state lines to exercise her constitutional right. That’s what women had to do back when Chelian flew to Buffalo each weekend. That’s what Roe was supposed to have ended. But as we navigated a small maze of plush recliners in the recovery room, Miller said that those days had returned.

Almost half of the patients at Whole Woman’s Health in Las Cruces come from Texas. It’s an hour’s drive from El Paso, which in 2010 had two clinics—but one already closed, and the other one will if Miller’s lawsuit does not succeed. That would make El Paso the largest city in America (population 680,000) without a single abortion provider. Even now the clinic is so overburdened that many Texas women can’t get an appointment at the remaining clinic, and so they drive to Las Cruces instead.

Some travel much farther. A spreadsheet posted on the wall in the bathroom indicated that some patients have driven six hours from Lubbock, even 10 hours from the Dallas suburb of Waxahachie. “Charlie,” a 25-year-old student, had come from West Texas, five hours away. She wore a waffle tee that showed off an intricate tattoo on her sternum—inspired, she said, by her tightly knit group of friends.

Ironically, the fact that Miller opened a clinic in Las Cruces is now being used to fight her lawsuit: The state of Texas has acknowledged that under the new restrictions, El Paso women would live 1,100 miles, round-trip, from the nearest Texas abortion clinic—but, state lawyers noted, Whole Woman’s Health in New Mexico is only an hour away from El Paso. The 5th Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with that logic, although the real test lies with the Supreme Court.

While Texas has been the epicenter of the debate over abortion access, the broader story goes far beyond its borders. In many ways, the successes of abortion opponents could read like a real-life example of what political strategists call “moving the Overton Window,” or shifting the parameters on what are publicly—and therefore politically—acceptable options between two extremes. As this political theory goes, apply the right pressures, and over time the window can shift and radical ideas can become mainstream. Many abortion opponents have abandoned violent protests and clinic bombings to push for restrictions that purport to be about informed consent (waiting periods) or safety (surgical facilities).

Where providers like Miller and Chelian see an extreme public health crisis, abortion foes see progress. Charmaine Yoest, the president of Americans United for Life, says that “apocalyptic” stories about abortion restrictions are not “an accurate representation.” AUL, which has written most of the model abortion legislation adopted across the country, is responsible for the recent wave of restrictions. Yoest claims that Roe v. Wade implicitly permits abortion for any reason at any time during pregnancy; the legislative changes AUL champions are moderating forces on an otherwise radical and dangerous law.

Because AUL’s measures seem reasonable, not only can legislators from red districts use them to rally the base, but those from purple districts can get behind them without facing a backlash. But the effects of these seemingly moderate and sensible abortion restrictions have, in fact, been breathtakingly radical.

A clinic called the Cherry Hill Women’s Center in southern New Jersey is seeing more and more patients from Virginia—they travel that far because clinics in Maryland and Delaware are overbooked—and the Midwest, where many clinics have shut down. Ohio has closed 7 of 16 clinics since 2011. Women from Ohio and Indiana have increasingly crossed state lines to go to Chelian’s clinics in Michigan.

In many states, women also have to plan their long journeys around an obstacle course of abortion restrictions. Thirteen states, including Texas, have introduced laws that require women to make an extra clinic visit—usually for anti-abortion counseling—24, 48, or even 72 hours before they can get the procedure. Sarah Roberts, a researcher with a project called Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health at the University of California-San Francisco, found that Utah’s three-day waiting period caused the average woman to delay her abortion eight days. The delay cost women money (in Texas, women who pay out-of-pocket spend an average of $141 on these extra visits) and forced them to have to tell more people about their abortions. Roberts met one woman who couldn’t get an abortion because the delay prolonged her pregnancy to the second trimester.

Fewer abortion clinics also means longer waits, which can mean a more complicated and expensive procedure. In the past year, the TEA Fund has helped 402 women pay for abortions but was asked for help by an additional 2,569. It had to double the average amount of money it spends per patient from $100 to $200.

“You really only get to give people good news for maybe the first couple hours of your shift,” says Desirae Embree, a graduate student at Texas A&M University who volunteers for the fund. “From then on, you’re probably going to be calling people who are desperate and need help to tell them that there’s no more money left, and they need to try again.”

Jo Wunderlich, who also volunteers at the TEA Fund, recently took a call from a young woman who’d just sold her car to pay her rent. To raise money for her abortion, she pawned her TV. The TEA Fund gave her $200, the maximum Wunderlich was authorized to give, but she was still several hundred dollars short. “I know she’ll be fine,” Wunderlich said, as much to herself as to me. “She’s in her first trimester. She still has time to raise the money.”

The Baltimore Whole Woman’s Health clinic where I met Miller is decked out with purple walls and furniture. It’s Miller’s ideal clinic: There are Margaret Cho aphorisms stenciled on the walls, and women can bring their husbands, friends, or families with them into the procedure room. To lessen the intimidation factor, staff gave the lab and ultrasound rooms names like the Patti LaBelle Room. Patients get abortions in the Reba McEntire Room.

By contrast, the “ambulatory surgical center” (ASC) where Texas wants to abortions to take place is a hulking facility intended for outpatient surgery. There are strict square footage standards and requirements for pricey equipment—like scrub sinks and air filtration systems—that doctors simply don’t need for first-trimester abortions. In some cases, it costs providers about 40 percent more in utilities and property taxes to run an ASC. That is, if they can raise the funds—several million dollars—to build them. In addition to Texas, 24 other states have passed legislation to require many abortions to be performed in such facilities, although litigation is pending in two of those states.

“It really changes the nature of the practice,” said Carole Joffe, who has studied abortion providers for decades through the UC-San Francisco project. “Beyond the financial demands of what ASCs mean,” she said, “what these restrictions have done—and it’s so cruel—is they’ve struck at the heart of how good abortion care has been visualized for so long.”

The laws requiring abortions to take place in ASCs are not intended to shutter abortion clinics, abortion foes insist. Abortion should simply be treated like other surgical procedures, says AUL’s Kristi Hamrick. “The states themselves have a standard for locations that want to engage in some kind of surgical procedure,” she says. “The abortion industry is acting like somehow the pro-life movement went out with a tape measure to create these standards. It’s not AUL that’s dictating the size of the hallways.”

But mainstream medical groups are unequivocal that the vast majority of abortions do not require such precautions. Ninety percent of abortions take place in the first trimester. The procedure is typically performed while the woman is under mild sedation or awake and under local anesthesia. The doctor places a speculum in the vagina, dilates the cervix, and uses a suction device—which can be electrical or as simple as a small plastic syringe—to remove the pregnancy from the uterus. Afterward, most women spend an hour or so with a heating pad to ease cramps before going home. Complication rates are incredibly low; abortion is 40 times safer than a colonoscopy. Many abortion providers willingly operate surgical facilities so they can perform more complicated abortions, which are more likely to arise in the second trimester.* But the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has reviewed decades of evidence and determined that most abortions are safe to perform in a properly equipped doctor’s office.

AUL’s Yoest disagrees: “I find it really offensive when they make these kinds of arguments. The abortion industry wants to try to convince the American public that they should be allowed to maintain unsafe businesses under the guise of access. For them to say, ‘We can’t meet health and safety standards, so we should be allowed to continue operating,’ it defies common sense.”

To see the potential future of abortions in Texas, I went to the Planned Parenthood clinic in Dallas. It’s a charmless, concrete behemoth that was once used for knee, hernia, and rotator cuff surgeries. Planned Parenthood purchased it in 2014 for $6.8 million.

Kelly Hart, the director of government relations for Planned Parenthood of Greater Texas, gave me a tour. The size makes it easy for us to lose track of each other when I stop to look around, and I find her by the clacking of her heels. Occasionally, the sound is swallowed up by construction noises. This was the only location Planned Parenthood could purchase in its desperate hurry, and it’s way too big for its purposes. Case in point: To comply with Americans With Disabilities Act rules, the group is forced to build an elevator where the back door used to be.

“Part of me is humiliated that I even have to talk to you about an elevator,” Hart shouts over the caterwauling of a circular saw. “A fricking elevator.”

Hart clicks through the door of an operating theater. It’s about the size of a starter apartment, and it’s slightly cozier than a meat locker. Planned Parenthood wanted to decorate the barren white walls with art. But ASC rules about dust control caused staff to reconsider. Above us, a set of cryptic-looking nozzles, for pumping nitrous oxide and compressed air, jut out from the ceiling like high-tech stalactites. “It’s frightening, isn’t it?” Hart says. “And there’s just no reason for that.” None of them have hoses attached; the doctors don’t need what they pump. At the nurses’ station, a row of blinking orange lights alerts us that the supplies are low.

“In my clinics, staff have scrubs on, but they can hold a patient’s hand,” Miller told me. “They can wipe away her tears.” Women wait for their turn in a reception area, she added, and they wear their own clothes. But in surgical centers like this one, all the patients are naked beneath their hospital gowns. “There’s no individuality.” Nurses disappear beneath bonnets and booties and surgical masks. Clinics can’t use heating pads any more, because they might harbor bacteria. These are appropriate safety measures for facilities where surgeons cut people open—but that’s not what happens in a first-trimester abortion.

Denise Burke, the vice president of legal affairs at AUL, derides Planned Parenthood’s new surgical facilities as “abortion megacenters.” But the paradox is obvious: Across the country, because of laws championed by AUL, “megacenters” have become the norm. In the states where they are successful, reality is reminiscent of a classic Onion article: “Planned Parenthood Opens $8 Billion Abortionplex.”

Of course, for the last 15 years, abortion hasn’t necessarily required a “procedure” at all. Since the Food and Drug Administration gave its approval to RU-486—a.k.a. the abortion pill—in 2000, more than 2 million women have ended their pregnancies using medication alone. The ease, privacy, and efficiency offered by this method comes with great advantages.

Take Iowa. Planned Parenthood has seven clinics in the state where women can get the two types of pills necessary for an abortion: Mifeprex, which blocks progesterone, a hormone that is vital to a pregnancy, and misoprostol, which causes uterine contractions that flush out the pregnancy.

Medication abortion is ideally suited for a rural state like Iowa because the doctor’s role is fairly uncomplicated. A doctor assesses a woman’s chart and vitals, explains how the pills work, and hands them over. The doses are spaced one to two days apart, and women can take the second dose at home. Because few Iowa doctors are willing to provide abortions, and the population is so dispersed, Planned Parenthood started to link patients to doctors over video chat—what’s called “telemedicine.” At any one of its seven clinics, a nurse seats a woman in a sparse room with a computer monitor. The doctor and the woman talk via video feed. Then, with a remote control, the doctor opens a drawer next to the woman containing her pills.

“I’ll say, ‘Okay, the drawer’s gonna pop open, kind of abrupt. Ready, set, go!’ And I click the button, and it just pops right open,” says Jill Meadows, a Planned Parenthood physician and its medical director for Iowa and Nebraska. “It’s not much different at all whether I’m in the clinic. It’s the same exact process.” Except it saves many women an eight- or nine-hour round-trip.

Which is why it has become another target of abortion foes, who have managed to ban telemedicine abortions in 17 states since 2011. In Iowa, the program was nearly eliminated: In 2013, Republican Gov. Terry Branstad appointed a Catholic priest who had lobbied against it to the nine-person state board of medicine, which promptly shut the program down—though it was saved in the end by the Iowa Supreme Court.

But the fight is not over. Abortion foes have also legislated the dosage of medication a woman may take. Typically, doctors now prescribe 200 milligrams of Mifeprex and 800 micrograms of misoprostol. That’s different from the amounts the Food and Drug Administration originally approved when RU-486 first arrived on the scene in 2000. And while such tweaking is common in medicine as new evidence accumulates, five states (Iowa is not one of them) have now passed laws requiring doctors to prescribe abortion pills according to the original, outdated FDA guidelines.

Those older dosages make the medication harder to tolerate—failure rates more than double, and almost every woman experiences at least one severe side effect like nausea, vomiting, or cramps. Many abortion providers simply refuse to prescribe abortion drugs under these rules. I found only one provider, David Burkons of Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio, who uses the old dosages and was willing to talk about it on the record. “I explain it to patients. I explain there could be these effects,” said Burkons, not a little defensively. “And still, there are people who, this is what they want to do.” The whole thing requires four trips to his office: Once to hear Burkons read a script describing the fetus, which is required by the state, once for each dose, because the old guidelines prevent them from taking the second dose at home, and a fourth time for a follow-up. Women often bleed after the second dose—only now it’s in their cars instead of at home. Because the old rules require a higher dose, the procedure currently costs an extra $160.

And it gets more Kafkaesque: Since Burkons started prescribing abortion pills under the rules promoted by abortion opponents, he has reported 17 instances of patient complications to the state health department. Almost all of those women had experienced incomplete abortions—an inevitable outcome when using the outdated dosage. Operation Rescue, an anti-abortion group, got hold of those reports and splashed them across its website. “His dangerous abortion operation should be closed permanently,” said Troy Newman, the group’s president, “in order to protect women.”

The extra time and money involved has skewed the patient population toward women who are white, educated, and insured, says Ushma Upadhyay, a researcher for the UC-San Francisco project who has been studying Ohio. Also, as a result of these new requirements, the number of medication abortions has plummeted. One group of Ohio clinics Upadhyay looked at provided 2,172 medication abortions the year before the law went into effect. In the three years after, the same clinics provided on average only 545 a year—a 75 percent drop.

In June 2013, Chelian was at the Center for Choice, an abortion clinic in Toledo, Ohio, on the day that it shut its doors forever. In its 30 years, the clinic had survived fire bombings and aggressive protesters. What finally shuttered it was a new law requiring abortion clinics to enter into a “transfer agreement”—a contract with a local hospital to take any patients having complications. But all of Toledo’s hospitals refused to make a deal with the clinic.

“This woman had put her life into this clinic, and everything was in boxes,” Chelian said. “All we did was sit around and cry.” Women knocked on the door to ask if they could still get an abortion. The phone rang until someone began forwarding the calls to Chelian’s Northland clinic an hour away. On the way home, the group stopped to get a stiff drink. It felt like they had just attended a funeral.

At her own clinic, Chelian spends thousands annually on security guards. Recently, a new abortion restriction forced her clinics to pay $25,000 to install seven unnecessary scrub sinks. “We’re spending a lot of money to do this,” Chelian said. “And we could shut down any minute.”

Joffe, the UC-San Francisco researcher, points out that in the past, anti-abortion activists targeted providers and made them victims of sustained violence. Protesters chained themselves to the front doors of clinics, a radical tactic that turned public opinion in clinics’ favor. Doctors feared for their lives. Some were maimed or murdered.

Today, clinics are more preoccupied with what Joffe calls state-sanctioned harassment. “In some ways, this is worse,” she says. “TV stations don’t go to a clinic to cover the fact that you can no longer give a patient a heating pad. Admitting privileges? Well, that sounds reasonable. Why are these pro-choice fanatics making such a fuss? It’s not policemen coming to get the protesters off your back anymore. It’s inspectors coming to shut you down.”

The effects on staff morale can be corrosive. In Michigan, a new law requires a woman to print and read anti-abortion literature 24 hours before her abortion. When she prints the documents, they bear a time stamp. At least once a week, a woman appears at the clinic who read the documents the day before but couldn’t print them until the morning of her procedure (poor women, especially, suffer because they use their phones as computers). Chelian’s staff has to turn the women away, and the women become furious—at them.

“The staff went into the work to be advocates and feminists and supporters of women—and we’re the people who inform the woman about the law,” Miller says. The patients’ experience “is one of oppression. And the very woman we’re there to help sees us as the enforcer.”

The struggle just to stay open is all-consuming. In Texas, the rules, protocols, and requirements for Miller’s entire staff change every two years, she says. Administrative workers must record the same data in twice as many logs. They prepare multiple records fearing still more inspectors.

“We dance faster, and we bend over, and we comply, comply, comply, until we pick up our head and say, ‘What are we doing here?'” Miller said. “I’m trying so hard to keep the doors open, but for who?” The rules change so frequently that even if her lawsuit against the Texas law succeeds, Miller is not sure if she would ever open a new clinic in Texas.

But she acknowledges that the need is desperate. One of the women I met in the Las Cruces waiting room, Suhey, an 18-year-old from El Paso, said she had already tried to give herself an abortion with Mifeprex a friend bought in Ciudad Juárez. (It didn’t work.) Suhey already has a daughter—the lock screen on her phone shows the two of them snuggling—and is caring for her 16-year-old sister. She can’t afford another child.

Researchers are investigating whether self-abortion attempts are on the rise. Chelian doesn’t need convincing. Recently, a woman came to her clinic who tried to pierce her cervix with a drinking straw.

It frightens Chelian that with every passing year there are fewer women like her who can recall what abortion was like before it was legal. “What they don’t know anymore, what’s gotten lost in the history, is how many women died trying to give themselves abortions,” Chelian said. Some time ago, Chelian asked a class of college freshmen what they would do if restrictions kept them from getting abortions. “We’d use a coat hanger,” one young woman replied. “Like our grandmothers did.”

Correction: The original version of this article, which ran in our September/October 2015 issue, misstated that there is a consensus among abortion providers about where second-trimester procedures should take place.