Bill Clark/AP

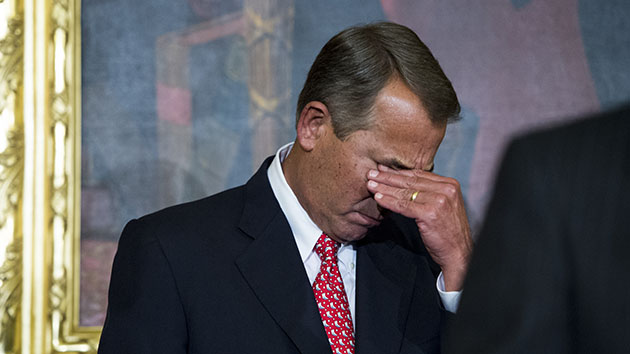

When Congress announced a budget accord on Monday night to keep the government funded for the next two years, Republicans boasted that they scored a victory against the plague of President Obama’s health care reform law by striking a section of the original law. “By eliminating the law’s auto-enrollment mandate that forces workers to automatically enroll into employer-sponsored health care coverage that they may not want or need, we will repeal another major piece of Obamacare,” soon-departing House Speaker John Boehner crowed in a press release.

But dig into the details, and that supposed victory doesn’t amount to much in terms of policy. “It’s not a big deal,” says Gary Claxton, a vice president at the Kaiser Family Foundation, a nonprofit focused on health care, noting that it’s “nothing that you’ll ever notice” if the budget deal becomes law.

The provision in question is a small section from the Affordable Care Act, better known as Obamacare. It would require companies with over 200 full-time employees that offer insurance to enroll all new employees onto the company’s health plan automatically. Employees would still be able to decline the insurance if they preferred. Currently, employees usually must actively opt into employer-based health care plans.

But the auto-enrollment provision has never gone into effect. The Department of Labor has continually punted on writing the actual regulation, and all the stalling has led experts to doubt whether the policy would be implemented anytime soon—with or without this proposed budget deal. Employers expressed dissatisfaction with the rule after the Affordable Care Act became law, and confusion over auto-enrollment ran the risk of placing workers in plans they didn’t want or enrolling their spouses who already had coverage. “Employers didn’t like it, a lot of labor organizations don’t like it,” Claxton says. “And there are some messy issues associated with it. I don’t think there’s a lot of people clamoring to keep it.”

Much like the budget bill’s supposed cuts to entitlements, which leave beneficiaries largely untouched, this reversal of a portion of Obamacare will have little impact in practical terms, even if it’s likely to be used for political ends. Republicans gain a rhetorical victory they can sell to the conservative base, while Democrats don’t lose anything on the substance of the policies.

The change will help offset the costs that the budget deal added by lifting earlier caps on government spending. The Congressional Budget Office has projected that 750,000 more people would end up with insurance each year thanks to auto-enrollment. Because expenditures on employer-provided health care are exempt from taxes, auto-enrollment reduces federal tax revenue. Eliminating auto-enrollment is estimated to raise an additional $8 billion over the next decade.

But Claxton doubts the figure is that high. The CBO used acceptance rates for auto-enrollment of 401(k) plans as the baseline for its projections, he says, and decisions about health insurance are far more complicated than those about setting money aside for retirement. “Maybe it’s estimated too high,” he says. “I don’t think people should give CBO too much of a hard time about things like this, because there’s just no data to do a decent job of estimating this.”