Supreme Court Justice Sonia SotomayorThe Deseret News, Tom Smart/AP

Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan has referenced Dr. Seuss to get her point across during oral arguments. Justice Stephen Breyer on Monday drew an analogy to his grandson making excuses to avoid doing homework. Rhetorical devices take all kinds of forms on the bench. But Sonia Sotomayor might be the first justice in recent memory to invoke her own relatives in jail to make a point.

During oral arguments on Monday morning in Foster v. Chatman, a case involving racial discrimination in jury selection, Sotomayor questioned whether a Georgia prosecutor had used a bogus pretext to bounce an African American woman from a jury. The prosecutor had claimed he excused her because the woman’s cousin had been arrested on a drug charge. “There’s an assumption that she has a relationship with this cousin,” Sotomayor told Georgia deputy attorney general Beth Burton, who argued Georgia’s case before the court. “I have cousins who I know have been arrested, but I have no idea where they’re in jail. I hardly—I don’t know them…Doesn’t that show pretext?”

Her comments demonstrate the importance of her role as the first Latina justice on the court, an institution dominated by white men from privileged backgrounds. She asked the sort of question African Americans might welcome from Clarence Thomas, the only black justice, who rarely speaks from the bench. The insights she brings from her formative years in a Bronx public housing project are particularly applicable to racially charged cases like this one.

Monday’s argument stems from the case of Timothy Foster, an African American death row inmate convicted by an all-white jury in 1987 of murdering a white woman in Butts County, Georgia. The conviction came just months after the US Supreme Court had issued a decision in Batson v. Kentucky that was supposed to ban racial discrimination in jury selection. The decision has failed to bring an end to the all-white juries found in so many death penalty trials against black men. That’s largely because when defense lawyers have made a Batson challenge to an all-white jury, prosecutors have simply learned to justify decision to kick someone off a jury in supposedly “race-neutral” terms, and courts have accepted them.

For instance, defense lawyers have accused a St. Louis prosecutors’ office of creatively using the “postman’s gambit,” in which prosecutors strike people from a jury because they work for the US Postal Service. Prosecutors have argued that postal workers tend to be “disgruntled” and lack ambition, and that’s why they don’t want them on juries. But the majority of postal workers in the county are black, so this “race-neutral” reason for excusing jurors effectively keeps many African Americans off juries, especially in death penalty cases.

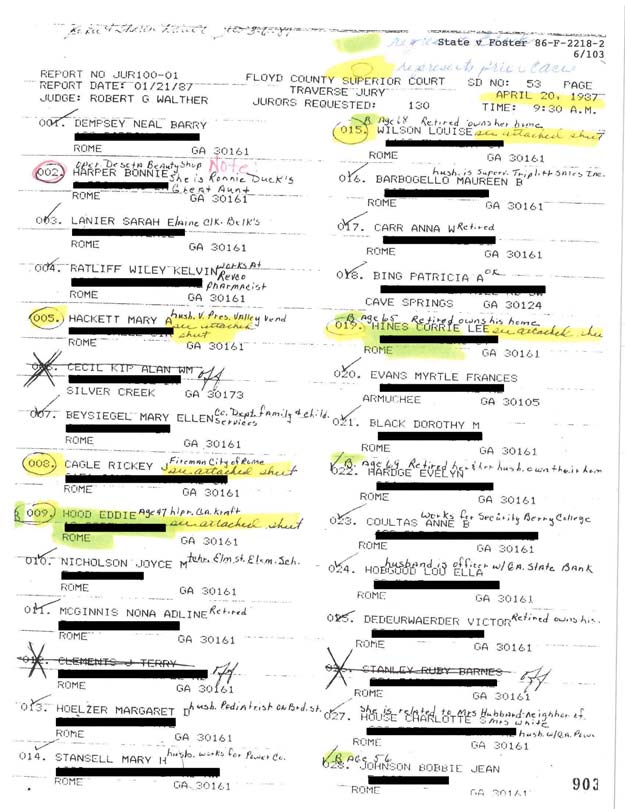

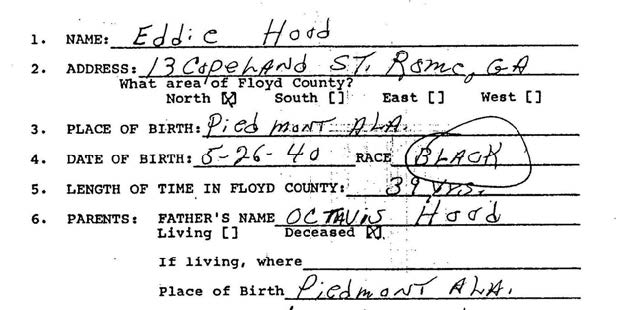

The Foster case has helped expose the farce behind these sorts of schemes. Foster’s lawyers argued repeatedly during the trial proceedings and on appeal that prosecutors had illegally kicked all the African Americans off his jury. But the Georgia courts accepted prosecutors’ arguments that their challenges to black jurors were not based on race, but instead on neutral things such as age and profession, or more nebulous but legal excuses such as “failure to make eye contact.”

District attorney Stephen Lanier at one point justified his actions in court by saying that during jury selection, he was trying to weed out women, not blacks, because they tend to have “serious reservations” against the death penalty. But in 2006, Foster’s lawyers filed an open-records request and obtained the prosecutors’ jury selection notes, which prosecutors had tried to keep secret. The notes, Justice Elena Kagan said Monday, are evidence of “as clear a Batson violation as this court is ever going to see.”

In the notes, prosecutors had highlighted the race of the black jurors on several different lists. On one list, under the heading “Definite NOs,” prosecutors listed six potential jurors, all but one of whom were black. The prosecutors ranked the prospective black jurors in case “it comes down to having to pick one of the black jurors.”

One of those black jurors they found potentially acceptable but still excluded from the jury was Marilyn Garrett, a woman whose story was often at the center of Monday’s arguments.

Foster’s lawyers argued that her case was one of the most egregious, in large part because the prosecutors provided false information about Garrett’s background to justify her exclusion from the jury. For example, a prosecutor said he kicked her out of the jury pool because she worked with low-income kids at Head Start, and because “her age [was] so close to the defendant.” Garrett was 34 at the time; Foster was 19. Prosecutors picked eight white jurors to serve who were closer in age to Foster than Garrett. During appeals proceedings, prosecutors repeatedly referred to Garrett as a social worker, a profession prosecutors claimed not to want represented on a capital jury. But Garrett wasn’t a social worker. She was a teacher’s aide, and prosecutors allowed every white teacher and teachers’ aide in the pool to serve on the jury. (Update: Late Tuesday, I managed to track down and interview Garrett, who recalls prosecutors treating her “like I was a criminal.”)

Lanier, the prosecutor, came up with a laundry list of other purported reasons why he dismissed Garrett, including that she said “yeah” to the court four times; she was divorced; and he thought she was lying when she said she didn’t know the neighborhood where the victim lived. In fact, Foster’s attorney, Stephen Bright, told the court, Garrett lived 18 or 20 miles away from the victim’s neighborhood. Meanwhile, another woman, who was white and also a teacher’s aide, taught in a school 250 yards from the victim’s neighborhood. “Both of them answered that they weren’t familiar with the area where the victim lived,” he noted. “But instead, Ms. Garrett is treated as a liar, and [the white woman] is accepted and actually serves as a juror in this case.”

In one of the appeals proceedings after Foster was convicted, Lanier came up with a new reason for why he dismissed Garrett from the jury: Her cousin had been arrested on drug charges. That argument alone might be enough to sink the case for Georgia, because court filings show Lanier didn’t even learn about the arrest until the trial was over. (Burton claimed Lanier did know about the arrest, but simply never mentioned it.)

At this point, Sotomayor issued her challenge to the relevance of that arrest and the prosecutors’ failure to question the potential juror about it. From the record in the case, it’s clear that all of the parties involved assumed that having a cousin arrested on drug charges should automatically disqualify someone from serving on a criminal jury. But Sotomayor blasted that presumption, drawing on her personal experience to question something that probably keeps millions of Americans, disproportionately minorities, from serving on a jury. She asked Burton to explain why the prosecutors didn’t question Garrett about her cousin during jury selection, in case it turned out that she, like Sotomayor, didn’t really know her troubled relative. Sotomayor suggested the cousin’s arrest was just a bogus excuse for getting a black person off the jury. Prosecutors hadn’t asked any questions, she said, because if they had, Garrett “might get off the hook on that,” and then they would be forced to let her serve.

It was a withering analysis from someone whose personal experience gives her an understanding of both the discriminatory practices at work and how prosecutors ought to do their job—Sotomayor was once one of those, too.

Sotomayor has been outspoken on the issue of race before, and also referenced her own history in making her case. Last year, she read a lengthy dissent from the bench, articulating her intense displeasure with her colleagues’ ruling in favor of a Michigan ballot initiative that banned race-based admissions programs in public colleges. She wrote then, “Race matters. Race matters in part because of the long history of racial minorities’ being denied access to the political process…Race matters to a young man’s view of society when he spends his teenage years watching others tense up as he passes, no matter what neighborhood he grew up. Race matters to a young woman’s sense of self when she states her hometown, and then is pressed, ‘No, where are you really from?'”

Sotomayor concluded in that dissent, “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to speak openly and candidly on the subject of race, and to apply the Constitution with eyes open to the unfortunate effects of centuries of racial discrimination.”

The Foster case offers an opportunity to do just that, and her performance during oral arguments suggests that she will have a strong influence on the outcome of the case. Her conservative colleagues, though, were clearly looking for a way to avoid that fight. They spent considerable time asking both sides questions about whether this case really ought to be heard in the Georgia Supreme Court, rather than the US Supreme Court, and whether the court should be reviewing the discrimination claims at all. Even if the court follows Sotomayor’s lead and finds that the prosecutors in Foster’s case discriminated against African Americans in the jury selection, the justices didn’t seem ready to do anything radical to fix the problems with Batson that are at the root of the issue. But they will be hard pressed to ignore Sotomayor’s moral authority as they make their decision.