It’s hardly surprising that a tobacco company would donate more money to Republican politicians than to Democrats, who are generally more amenable than GOPers to taxes and regulation. North Carolina’s Lorillard Tobacco, for instance, gave nearly four times as much cash to Republican candidates during the 2014 congressional election cycle. But the company made a striking exception for one particular subset of Democrats: African Americans.

Our analysis of records from the Center for Responsive Politics revealed that half of all black members of Congress received financial support from Lorillard, as opposed to just one in 38 nonblack Democrats. To put it another way, black lawmakers—all but one of whom are Democrats—were 19 times as likely as nonblack Democrats to get a donation.

It’s not hard to see why Lorillard might employ this strategy. Federal officials are now considering whether to add menthol, the minty, throat-numbing additive—to the list of flavorings Congress banned from cigarettes in 2009 for public health reasons. Lorillard’s Newport is the nation’s top-selling menthol brand, accounting for billions in annual sales. And who most favors menthols? Black smokers, by a wide margin.

For decades, in fact, the tobacco industry has maintained what amounts to an informal mutual-aid pact with certain black organizations. Over the years, cigarette makers have donated generously to members of the Congressional Black Caucus, and to its affiliate, the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation—not to mention the National Urban League, the NAACP, the United Negro College Fund, and many smaller African American groups. In return, some of these groups have helped the industry fight anti-smoking measures. Others, public health advocates say, have turned a blind eye to the harms tobacco imposes on the black community.

Menthols account for about 30 percent of cigarette sales in the United States, but according to a study cited by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) based on data from 2008 through 2010, menthols were the choice of 88 percent of black smokers—and 57 percent of smokers under 18.

The Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, the landmark 2009 law that authorized the FDA to regulate tobacco products, included a ban on candy, fruit, and spice flavorings because of their appeal to young smokers. But during the political negotiations that preceded the deal, menthol was given a pass. In July 2013, after years of complaints from the public health community, the agency put out a call for comments on whether menthol should be added to the list.

Several other countries have banned menthol in recent years, or imposed deadlines for eliminating it, but not been a peep has been heard from the FDA since it asked the public to weigh in more than two years ago. This past June, in a display of confidence, Reynolds American Inc.—the conglomerate that owns RJ Reynolds Tobacco Co.—completed a merger with Lorillard, paying more than $27 billion for a company that depended on menthols for roughly 85 percent of sales.

The FDA’s menthol limbo is part of a pattern, public health advocates say: The agency has been all but paralyzed by caution and—when it has tried to act—by legal challenges from the industry. In January 2010, the FDA lost a lawsuit from manufacturers opposed to its plan to regulate e-cigarettes as drug-delivery devices, but it has yet to complete the rulemaking process that would extend its oversight of ordinary tobacco products to cigars and e-cigarettes, which are increasingly popular among teenagers. In November 2011, the industry again blocked the FDA in court after the agency tried to require graphic warning labels on cigarette packs—similar to those used in at least 75 countries.

The menthol delay is “inexcusable,” says Joelle Lester, a staff attorney with the Public Health Law Center in St. Paul, Minnesota. “Prohibiting menthol in tobacco products should be a very high priority.” (Agency officials declined to be interviewed. A spokesman noted in an email that the FDA “is continuing to consider regulatory options related to menthol.”)

Getting rid of menthol would be politically difficult under any circumstances, but observers say it will be impossible without strong support from African American leaders. And despite support for a ban from some black public-health advocates, the community’s leadership organizations and politicians have been largely silent. Some of the smaller groups that have accepted tobacco money over the years—including the National Black Chamber of Commerce, the Congress of Racial Equality, the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives (NOBLE), and the National Black Police Association (NBPA)—are actively opposed to a ban, claiming that it would trigger an illicit trade in menthol cigarettes. This, they argue, would result in lost tax revenues, higher law enforcement costs, and widespread arrests in the black community.

The NBPA launched a write-in campaign that resulted in more than 36,000 comments opposing a ban, according to an FDA document (PDF). And while that group did not respond to interview requests, John Dixon, a past president of NOBLE and the police chief in Petersburg, Virginia, told me he thought a menthol ban “would probably have an adverse effect on the minority community,” adding that “prohibitions cause a whole other host of problems,” including a “burden on law enforcement.” NOBLE currently lists RAI Services Co.—part of Reynolds American—as one of its financial backers. But this “would not have any influence, one way or another,” on the group’s positions, Dixon insists.

The relationship between Big Tobacco and black groups “is complicated,” notes Delmonte Jefferson, executive director of the National African American Tobacco Prevention Network, a CDC-funded nonprofit. In recent years, minority groups have attracted a wider range of corporate sponsors, making tobacco money less important. But “there was a long time that it was only the tobacco industry that would support” some of them, Jefferson said. “To do an abrupt turn against the same companies—that’s kind of hard for them to do.”

While smoking rates for black and white adults are comparable, blacks have disproportionately higher death rates from tobacco-related ailments, including various cancers and cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. About 47,000 African Americans die annually from smoking-related illnesses, the CDC reports, making tobacco the black community’s greatest preventable cause of death.

Menthols do not appear to be any more toxic per se than regular cigarettes. “A menthol cigarette is just another cigarette and should be regulated no differently,” David Howard, a spokesman for Reynolds American, writes in an email. But health authorities view menthols as a starter product. saying that menthol’s anesthetizing effects help beginners tolerate the harshness of tobacco smoke, making them more likely to become addicted to nicotine.

“Menthol has no redeeming value other than to make the poison go down more easily,” notes a report in the American Journal of Public Health. Some research also suggests that menthol smokers are more nicotine-dependent and have more trouble quitting. It is “likely that menthol cigarettes pose a public health risk above that seen with non-menthol cigarettes,” states a 2013 FDA report. The industry disputes this. “The best available scientific evidence,” the Reynolds spokesman claims, “demonstrates that menthol cigarettes do not cause people to start smoking earlier, smoke more cigarettes…or make smokers more addicted than non-menthol cigarette smokers.”

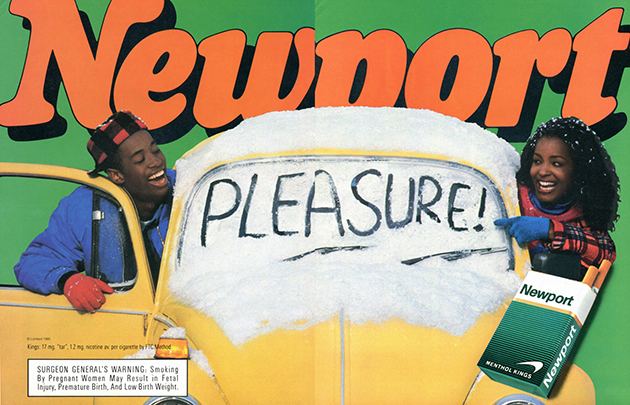

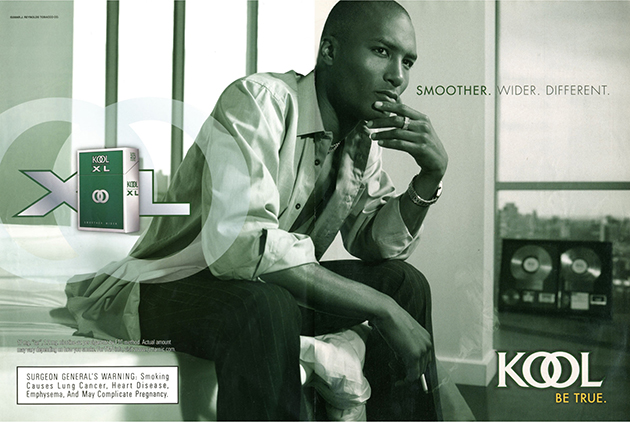

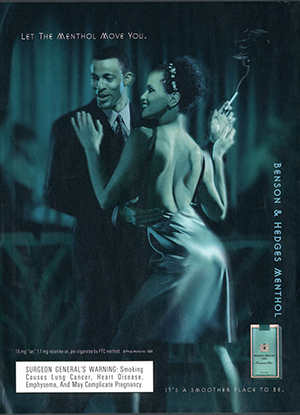

In any case, Big Tobacco has worked hard to befriend the black community. Early on, cigarette makers touted menthols as good for smokers with a cough or cold, and “African Americans became attached to the notion” that menthols were safer, according to public health activist and researcher Phillip S. Gardiner. The companies reinforced the popularity of Kool and other brands by sponsoring cultural events and pouring marketing dollars into black media and neighborhoods—all part of what Gardiner calls “the African Americanization of menthol cigarette use.”

The industry’s hiring practices were also quite progressive for their time. During the 1950s, the White Sentinel, a white supremacist publication, urged a boycott of Philip Morris for having “the worst race-mixing record of any large company in the nation.” Philip Morris “was first in the tobacco industry to hire Negroes instead of Whites for executive and sales positions,” the publication lamented, and “the first cigarette company to advertise in the Negro press.”

Indeed, Philip Morris—America’s top cigarette maker and part of Altria Group—led the way in making tobacco companies charitable pillars of black cultural, educational, and political organizations. In 1987, for instance, the company donated $2.4 million to more than 180 black, Latino, and women’s organizations and their local chapters.

That same year, the National Black Monitor, a now-defunct magazine, published an article ghost-written by an official from RJ Reynolds—a tobacco company that funded journalism scholarships for African American students and in 1985 was named advertiser of the year by a black newspaper publishers group. The article compared the treatment of tobacco companies to that of oppressed blacks. While racial minorities no longer face “the systematized injustice they once did,” the writer argued, “relentless discrimination still rages unabashedly on a cross-country scope against another group of targets—the tobacco industry and 50 million private citizens who smoke.”

At the NAACP’s annual convention in 2009, two delegates from the group’s Berkeley, California, branch tried to convince the organization to take a stand against Big Tobacco. The two, Valerie Yerger, then an assistant professor of health policy at UC-San Francisco, and Carol McGruder, co-chair of the African American Tobacco Control Leadership Council, tried to introduce a resolution that called on NAACP leadership to make tobacco control “a national priority” and push for a menthol ban.

The measure hadn’t been vetted by the NAACP’s resolutions committee, as was customary, and the women’s request to introduce it on an emergency basis was not well received. The late Julian Bond, then the group’s chairman, “was not going to have any conversation with us about this,” Yerger recalls. “He was in our face yelling at us, okay? I was determined not to cry, but this was, like, a hero that I grew up with,” she adds. “As a young black kid, you grow up knowing who the hell Julian Bond is.” McGruder doesn’t recall Bond yelling, but “he wasn’t happy about it and he wasn’t going to entertain it,” she says.

The flow of tobacco money to minority groups seems to have ebbed in recent years. But the industry “still has a pretty heavy influence financially,” says Jefferson of the National African American Tobacco Prevention Network. Last year, for instance, Altria gave $1 million to Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

During the 2013-14 election cycle, tobacco companies donated $115,650 to black lawmakers and their affiliated PACs, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. Lorillard was the most generous, distributing $56,500 to 23 black members (there are 46 total) and their PACs. The Black Caucus chair, North Carolina Rep. GK Butterfield, got $5,000 from Lorillard. Rep. Sanford Bishop of Georgia got $10,000. South Carolina Rep. James Clyburn received only $2,000, but his BRIDGE PAC took in $5,000 from Lorillard and $10,000 from Altria.

Shuanise Washington is president and CEO of the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation, which sponsors leadership training, awards scholarships, and hosts an annual legislative conference attended by thousands. Washington, who declined to comment for this story, was also a past vice president for Altria, which gave the CBCF between $100,000 and $249,000 in both 2013 and 2014, according to the foundation’s website. In addition, Reynolds American is listed as having contributed between $5,000 and $15,000, and Altria was a corporate partner at the legislative conference in September. “How can you talk about health equity,” asks anti-tobacco activist Jefferson, “when you are sponsored by a killer of public health?” (An Altria spokesman said the company’s gifts to the foundation mainly support fellowship and internship programs, reflecting Altria’s “long history of focusing on diversity and inclusion.”)

Lorillard also gave a small donation to Rep. Robin Kelly of Illinois, who heads a panel called the Congressional Black Caucus Health Braintrust. At the caucus foundation’s legislative conference, the panel issued a 144-page report on the health problems afflicting minority citizens. It included entire sections on childhood obesity, nutrition, HIV/AIDs, lupus, sleep disorders, oral health, and gun violence. Tobacco was barely mentioned.

The 2009 legislation that gave the FDA power to regulate tobacco products grew out of a deal between anti-smoking groups, members of Congress, and Philip Morris. But the menthol exception did not sit well with some black public health advocates. “How do you justify removing all of the flavorings which were minuscule in use but leave the No. 1 flavor product? It makes no sense at all,” said William S. Robinson, the former head of the National African American Tobacco Prevention Network, which withdrew its support for the bill in protest.

Seven former secretaries of Health and Human Services weighed in with an open letter to Congress. “Menthol should be banned so that it no longer serves as a product the tobacco companies can use to lure African American children,” it read. “We do everything we can to protect our children in America, especially our white children. It’s time to do the same for all children.”

Lorillard, which donated $1 million to the International Civil Rights Center and Museum in its Greensboro hometown soon after, fought back via advertisements in black newspapers: “Some self-appointed activists have proposed a legislative ban on menthol cigarettes in a misguided effort to force people to quit smoking by limiting their choices,” one ad warned. “The history of African Americans in this country has been one of fighting against paternalistic limitations and for freedoms.”

Ultimately, Congress kicked the menthol can down the road. An amendment to the Tobacco Control Act called for the formation of a scientific advisory panel to study and report back to the FDA on the public health impact of menthol, “including use among children, African Americans, Hispanics, and other racial/ethnic minorities.”

The panel issued its report in 2011, concluding that “removal of menthol cigarettes from the marketplace would benefit public health in the United States.” The FDA, however, waited two more years before requesting public comments. Then, in July 2014, it suffered a legal setback. A federal judge ruled that the agency could not base any decisions on the advisory panel’s findings. The ruling emerged from a lawsuit by Reynolds and Lorillard claiming that the FDA had violated ethics laws by appointing experts who had conflicts of interest due to their previous anti-tobacco stands. The decision is under appeal. The FDA could have acted anyway, however, because its own staff had prepared a separate report that reached essentially the same conclusions as the panelists had. But for reasons agency officials won’t discuss, nothing has happened since.

Some activists have simply given up on the feds and moved on to local campaigns. In December 2013, for instance, the Chicago City Council passed an ordinance barring the sale of flavored tobacco products, including menthol cigarettes, cigars, and e-cigarettes, within 500 feet of schools. In Berkeley, Calfornia, a ban on the sale of menthol and other flavored tobacco products (including e-cigarettes) within 600 feet of schools will take effect in 2017. Similar legislation has been proposed in Baltimore. “I’m not expecting anything” from the FDA, says Carol McGruder, one of the anti-smoking activists rebuffed by the NAACP. “I don’t think that they have the guts.”

This story was reported by FairWarning.org, a nonprofit investigative news organization focused on public health, safety, and environmental issues.