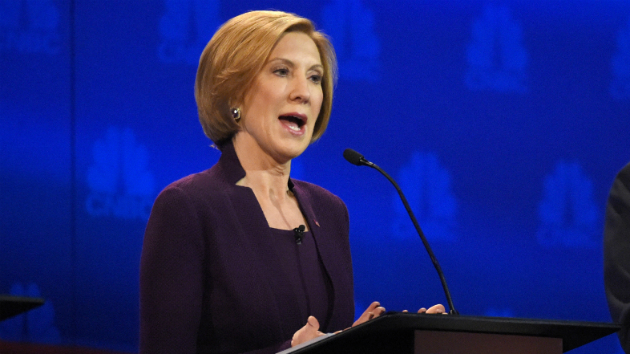

John Minchillo/AP

For more than a month, households in California have been receiving robocalls and mailings about abortion. “In California, a 13-year-old girl can have a surgical abortion without either of her parents ever knowing about it,” says the voice on the line, before asking recipients to sign a petition supporting a 2016 California ballot initiative that would require parental notification before a girl can terminate a pregnancy. The vaguely familiar voice making this pitch? Republican presidential hopeful Carly Fiorina.

Fiorina’s robocalls began in late September, barely two weeks after her fiery rebuke of Planned Parenthood at the second GOP debate catapulted her to the top tier of candidates in polling. These calls—which promise to reach millions of households in California—were paid for by Californians for Parental Rights, a fundraising committee whose founder has spent millions unsuccessfully pushing parental notification ballot measures in almost every California general election for the past decade. Getting a proposed constitutional amendment on the ballot requires a number of signatures equal to 8 percent of the number of voters in the state’s last gubernatorial election. This year, CPR will need to gather 585,407 signatures to qualify the parental notification measure for the ballot.

For this latest attempt, Fiorina is a valuable advocate. The one-time Silicon Valley CEO has emerged as the right’s new anti-abortion champion after ramping up her condemnations of Planned Parenthood on the national stage. At September’s GOP debate, she forcefully described grisly abortion footage she claimed to have seen in Planned Parenthood sting videos released this summer. A few weeks later, she accused the women’s health provider of spreading “propaganda” about her when the group insisted the video she described did not exist. Later in October, Fiorina retold the old story of her pro-life roots—accompanying a friend to an abortion procedure—but emphasized a new detail: “We went to a Planned Parenthood clinic.”

Now Fiorina is throwing her support behind a measure that has been the goal of California’s pro-life community for a decade, one that appears to be as much about draining the funds of the pro-choice groups as it is about protecting young women. When contacted for comment, Fiorina’s campaign didn’t address the candidate’s motivations for supporting this measure, saying only that “Carly is proudly pro life and was not compensated in any way.”

So far, the calls appear to have attracted more ire than support. Visitors to the Californians for Parental Rights’ Facebook page have voiced their frustration: “STOP HARASSING ME,” wrote one user. From another: “I’m sure I’m not alone in saying that unsolicited robocalls is [sic] not a smart way to get people to support your cause.” Similar reactions have proliferated on Twitter: “Just got an irritating robocall from @CarlyFiorina,” wrote one user. “Women are watching, and we vote! #prochoice.”

Jim Holman, the founder of Californians for Parental Rights, pushed to get parental notification on the state ballot in 2005, 2006, 2008, and 2011, making this his fifth attempt at passing the constitutional amendment. This kind of repetition for a defeated measure is virtually unprecedented in California, says Brian Adams, a political science professor at San Diego State University who studies the ballot measure system.

“There have certainly been initiatives that have been on the ballot multiple times,” says Adams. “But I’m not sure there’s any other one that’s been tried five times.”

Holman has bankrolled a large portion of these repeated efforts himself, spending more than $5 million in loans and direct contributions on parental notification measures since 2005—far more than any other donor. A conservative Catholic, he owns the San Diego Reader, one of the largest alternative weeklies in the country and publishes California Catholic Daily, a religious news site that sometimes runs anti-abortion and anti-gay content. The Vietnam vet and father of seven says in media interviews that he has been vehemently anti-abortion since 1989, when his newspaper ran ads featuring photos of aborted fetuses that were found in a storage container. That same year, Holman was arrested outside an abortion clinic in La Mesa, California during a demonstration by Operation Rescue, one of the more extreme anti-abortion groups, and spent two weeks in jail after being convicted of trespassing.

His legislative activism soon followed. In 1997, the California Supreme Court overturned a parental consent law on the grounds that girls under 18 had a right to privacy when deciding to have an abortion. That year, Holman donated thousands of dollars to mount a campaign against the justice who wrote the majority opinion, Ronald George, who was up for a retention vote as chief justice. When that failed, Holman turned to ballot measures.

The first effort, Proposition 73, made it onto the ballot for a 2005 special election. Planned Parenthood spent $2.3 million to defeat the initiative by about 5 points. Mere days after this loss, Holman launched a new petition to qualify parental notification for the 2006 election, where Planned Parenthood would spend $3.4 million to defeat it. In 2008, Planned Parenthood spent $6.5 million to defeat the latest version of the measure. In 2010 and 2011, Californians for Parental Rights filed two slightly different initiatives, five times each—10 attempts in total. None made it onto the ballot. In total, says Kathy Kneer, the president and CEO of Planned Parenthood Affiliates of California, Planned Parenthood and smaller donors have spent more than $17 million to quash this ballot measure over the years. “That is a huge sum for us,” says Kneer.

The majority of Holman and CPR’s funds and efforts have been spent on getting the measures to qualify for the ballot initially, rather than aggressive media campaigning once they are in play. That’s why some opponents believe Holman and his fellow abortion opponents are motivated not just by the content of the measure, but by its financial consequences for Planned Parenthood. (Holman could not be reached for comment.)

“If you are a multi-millionaire who’s spending $1.5 million in three consecutive general elections to qualify the initiative for the ballot, but then you don’t spend any of your millions on television commercials to attempt to actually pass that initiative, it definitely raises a red flag,” Vince Hall, vice president of Planned Parenthood of the Pacific Southwest, told San Diego CityBeat in 2011.

San Diego State’s Adams agrees that this theory is a real possibility: Presidential election voter turnout in California tends to skew liberal, he says, which means that even if the parental notification measure makes it onto the November 2016 ballot, it is not likely to win. “It makes sense that they’re doing it to drain funds from their opponents,” he says.

If the measure gets on the ballot, it would once again require Planned Parenthood to expend money and energy, says Kneer, and would boost Fiorina’s anti-abortion bona fides. What’s more—Fiorina’s support of the measure is a win-win for her and CPR. She can publicize her anti-abortion stance to Californians while evading campaign ad regulations, but she also brings clout to CPR’s oft-failed ballot measure. “I think they were pleased as punch that they got her to do a robocall,” says Kneer. “They may think they finally have a way to talk about this and leverage the presidential election. With Fiorina, I think they feel they have a little steam on their side.”