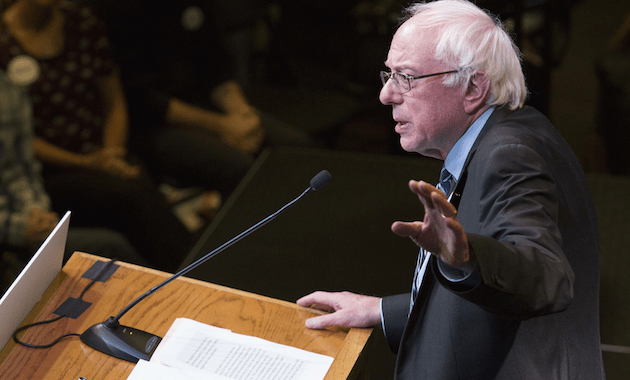

AP Photo/Toby Talbot

Editor’s note: Sen. Bernie Sanders jumped into the crowded 2020 race. This story was published during his first presidential bid. Click here for more Sanders stories from Mother Jones’ archives.

Bernie Sanders’ presidential bid is frequently likened to the 1920 campaign of Eugene Debs, the union leader and Socialist Party candidate who won nearly 1 million votes while serving time in prison for urging resistance to the draft. Sanders, who has called Debs “the greatest leader in the history of the American working class,” keeps a plaque celebrating the five-time presidential candidate in his Senate office, and he once recorded a 30-minute documentary about Debs’ political career, which he fought hard to air on Vermont public television. But Sanders’ rhetoric, ideology, and campaign coalition suggest a far more recent political model for his outsider campaign: Jesse Jackson’s 1988 run for the Democratic presidential nomination.

Jackson’s presidential bid was a transformative political development for the Vermont senator, then in his fourth term as mayor of Burlington. Never before had Sanders actively participated in a Democratic Party nominating contest. And until this year, he hadn’t done so since. But Sanders threw himself into the task of getting Jackson elected with the zeal of a convert, and in the process demonstrated a political dexterity that would later pave the way for his own unorthodox presidential campaign.

Even if it meant getting slapped in the face.

Initially, Sanders and his progressive allies in Burlington wrestled with the idea of whether to back Jackson’s candidacy. On the one hand, they considered Jackson’s organization, the Rainbow Coalition, a model for what they were trying to accomplish in Vermont—a lefty group that changed the political system from outside the party structure. Jackson, for his part, was an unabashed liberal who had no problem taking positions his more seasoned opponents wouldn’t touch. His platform even resembled the one Sanders would roll out during his own presidential run more than a quarter-century later—especially on such issues as income

On the other hand, Jackson was a Democrat. Sanders, a lifelong critic of the two-party system, had started off as a member of the third-party Liberty Union before becoming an independent. In 1986, he summed up his disdain for the Democratic Party: “The main difference between the Democrats and the Republicans in this city is that the Democrats are in insurance…and the Republicans are in banking.” He had endorsed Vice President Walter Mondale for president in 1984 in the least enthusiastic way possible, telling reporters that

Ultimately, Sanders decided that Jackson’s candidacy was just too revolutionary to ignore. He invited the reverend to Burlington, where they toured a child care center together, and Sanders endorsed him in front of a raucous crowd in Montpelier. As the campaign progressed and Jackson picked up steam, Sanders became more active. One month before Vermonters were set to cast their primary votes, he held a press conference to announce that he and his fellow Burlington progressives would be doing the previously unthinkable: attending the Democratic Party caucus.

“It is awkward—I freely admit it,” Sanders told the assembled reporters. “It is awkward for me to walk into a Democratic caucus. Believe me, it is awkward.”

But, he explained, he and his allies were driven by an even stronger impulse. “We see a historical moment here where we [have] a candidate who is the strongest candidate that working people and poor people have ever had, okay?” To ignore that would have been “tragic,” because in his view Jackson was the most consequential candidate in 50 years, if not ever—including Debs.

“Politics is a funny thing, you know?” Sanders said. “You could be rigid, you could say, ‘Hey, I’m not a Democrat, I’m not participating’—you could do that. I think that that would be a mistake, and I think when you’re in politics—when you’re dealing with life and death issues…you’ve got to be fluid. You’ve got to be flexible.”

Sanders did show up at the Burlington caucus that April, awkward as it was, and he delivered a spirited endorsement speech casting Jackson’s candidacy in decidedly Sanders-like terms.

“Tonight we are here to endorse the candidate who is saying loud and clear that enough is enough, that it’s time that this nation was returned to the real people of America, the vast majority of us, and that power no longer should rest solely with a handful of banks and corporations who presently dominate the economic and political life of this nation,” he declared. “It is not acceptable to him, to me, or to most Americans, that 10 percent of the population of this nation is able to own 83 percent of the wealth, and the other 90 percent of us share 17 percent of the wealth.”

Sanders received an icy reception at the caucus from some Democrats, who stood up and turned their back to the stage during his address. “And when I returned to my seat, a woman in the audience slapped me across the face,” Sanders recalled in his 1998 book, Outsider in the House. “It was an exciting evening.”

Jackson went on to win the Vermont caucus, one of his handful of victories outside the South. If there was a lesson in the Jackson campaign for Sanders, it was “realizing he didn’t always really need to be in opposition to the Democrats,” says Greg Guma, a Burlington progressive activist who joined Sanders in supporting Jackson. In essence, Sanders had formed his first political alliance—one he would continue in 1990 when he won his first congressional election with Democratic endorsements. After that, he began huddling with Democrats on Capitol Hill, and he formed the House Progressive Caucus, which included mostly Democrats. “Bernie is viewed always as an idealist,” Guma notes. “But at the same time you have to recognize that this is a fairly pragmatic politician that will drive his agenda forward, and he makes alliances based on this practical calculation.”

Throughout the 1988 campaign, Sanders maintained that Jackson would have been better off running as a third-party candidate. And he told Mother Jones in 1989 that the time was right for a new lefty party to challenge Democrats, as he had done in Burlington. But Sanders had no regrets about his endorsement. When Sanders arrived in Washington as a first-term congressman-elect, Jackson—along with Ralph Nader—hosted a “welcome to DC” event for him at Eastern Market. A grungy looking band played “This Land Is Your Land,” as balloons fell from the rafters.

But the 1988 campaign marked a critical step in Sander’s political evolution from activist and rabble-rouser to politician, and provided him a blueprint he would follow going forward. In a break with his previous electoral endeavors, Sanders had shown that revolutionary change was worth a compromise. Last month, when he told ABC News “I am a Democrat now,” it marked the culmination of a process that had begun 27 years earlier.