<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/gallery-780793p1.html?cr=00&pl=edit-00">Mahathir Mohd Yasin</a>/Shutterstock

This past fall, in the wake of a New York Times investigation, Coca-Cola released a list of all the organizations to which it had made donations for research and advocacy over the past five years. On the list were dozens of universities, medical groups, and fitness programs, some of which downplayed the relationship between soda and obesity.

Coca-Cola isn’t alone. The soda giant, together with PepsiCo, Hershey, Nestle, and others, runs and bankrolls the Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation, an organization that, in turn, wholly funds a health curriculum that’s been taught to millions of elementary schoolers across the country. Through a series of classes, games, and other exercises, kids learn they can eat anything so long as they exercise enough.

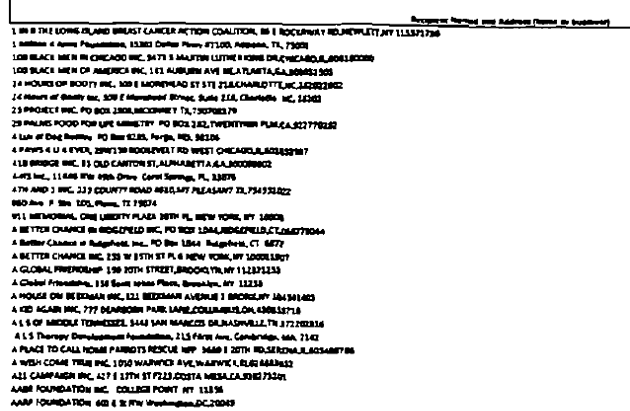

I looked into the Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation in this recent piece—which was how, a few weeks ago, I ended up squinting at the tax filings of the PepsiCo Foundation. PepsiCo is the corporate parent of Pepsi, Gatorade, Doritos, Tropicana, and other name brands, and each year, the foundation gives roughly $30 million to a variety of charities. When I downloaded the forms from the past few years on GuideStar, a go-to database for tax filings submitted to the IRS, I encountered a problem: The list of grantees, which is more than 40 pages long, was in a type that was so small it was virtually illegible. Here’s a screenshot of a zoomed-in part of the list, and here’s a link to the whole 2014 document.

When I emailed PepsiCo asking for a more legible version, a company representative replied, “We only have similar PDFs. Apologies for that.” I noted that the information is legally required to be publicly available. She wrote, “The information is publically [sic] available as you found. The docs I have are the same. Is there specific information you are looking for?”

As it turns out, the IRS specifies that when putting together 990s, organizations should “make sure the forms and schedules are clear enough to photocopy legibly.” When I noted this in an email, the representative insisted that “the Foundation could only find versions that were the same as the copies publically available through the IRS.”

GuideStar representative Jackie Enterline told Mother Jones that such small type in a tax filing is “not something we have seen before.”

Neither has Marc Owens, a tax lawyer who ran the tax-exempt organizations division of the IRS for 10 years. PepsiCo matches employees’ donations to charities, and it appears that the bulk of the list is small, matching gifts. Owens suspects that in an effort to make the 990 easily downloadable, the foundation made the list in a small size—but overdid it. “I guess what they decided to do is, rather than put them in a more legible size, they have 44 pages of this microdot stuff.”

He also pointed out a separate problem: The foundation’s 990s fail to include a required schedule explaining where the foundation’s assets—$53 million in 2014—are invested. For foundations with large endowments, this schedule, which documents virtually all the financial transactions over the course of the year, typically makes up the bulk of the 990.

I sent two more emails to the PepsiCo rep asking for the missing schedules and legible versions of the 990s, and I didn’t hear back. It was only after sending a third email that made clear that my piece would focus exclusively on the PepsiCo Foundation that, less than a day later, the rep sent me three years’ worth of clear 990s and the missing schedules, explaining that she hadn’t sent them before because she “didn’t have the context by which you were asking for the information.” The missing schedules, she said, were an “inadvertent omission,” and the money in question is invested in government Treasury bills. The font was small because the foundation wanted “to make the data required fit.” The rep acknowledged that when the documents are scanned, as they are when submitted to the IRS, the “quality is slightly diminished.” But, she wrote, the missing schedules and illegibility “in no way impact the Foundation’s positive work.”

IRS representatives declined to comment on the missing schedule and illegibility of the lists in the three years of tax filings.

The legible version of the 990s that the rep sent me do reveal some interesting, though not particularly surprising, contributions: Like Coca-Cola, PepsiCo has made millions of dollars in donations to support educational programs for kids promoting exercise and healthy diets, through organizations including United Way, GenYouth, and CitySquare. It also donated roughly $300,000 to the American Heart Association and $16,000 to the American Diabetes Association in matching gifts. (Here are the 2012, 2013, and 2014 legible versions.)

The reality, though, is that while the PepsiCo Foundation is required to list its donations, that same requirement doesn’t apply to PepsiCo’s corporate entity. Indeed, the millions of dollars that Coca-Cola donated to research that shifts the focus away from diet and toward exercise did not come from the foundation, but from the company itself.

When I asked the PepsiCo rep if the company had plans of being more transparent about its corporate spending like Coca-Cola had, she said, in short, that it didn’t. “Through our sustainability reports and our website, our efforts are well documented,” she said. Neither contains a full list of grantees or partnerships. When it comes to where PepsiCo’s money is spent, she maintained that the company is “transparent in our efforts.”