Hummelstown, Pennsylvania, Officer Lisa Mearkle leaves her arraignment on third-degree murder and manslaughter charges. She was later acquitted.Associated Press

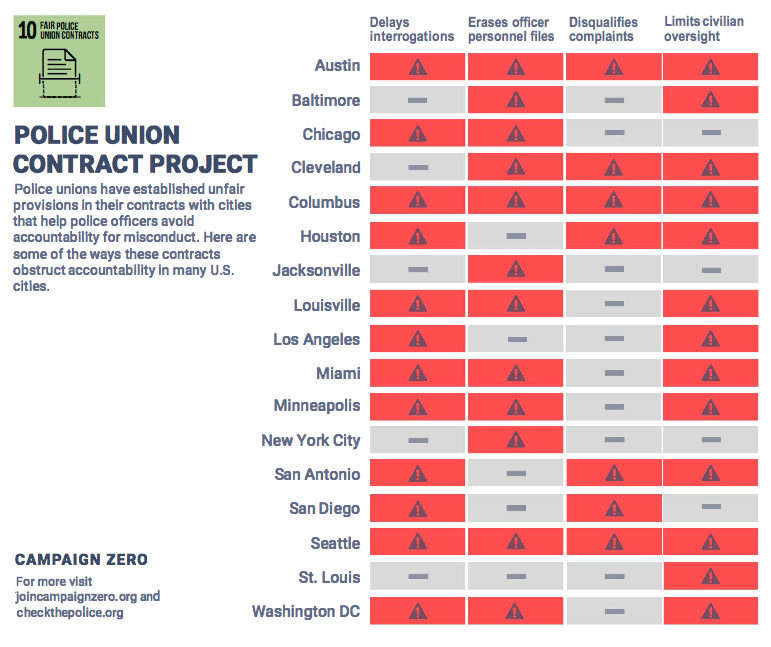

The police reform advocates who have long argued that cops shouldn’t be allowed to investigate themselves for wrongdoing now have some new data to back them up. Earlier this month, four activists affiliated with the Black Lives Matter movement launched Check the Police, a database of police union contracts from departments in 50 cities. After scrutinizing the documents, the project’s creators identified four key provisions by which the contracts shield officers from accountability, or receive rights and courtesies not available to most civilian suspects. These common provisions stipulate:

1. That an accused officer cannot be interrogated within 24 hours of an incident.

2. That complaints be expunged from an officer’s personnel file and destroyed after five years.

3. That complaints against an officer submitted more than 180 days after the contested incident be disqualified, along with complaints that require more than a year to investigate.

4. That civilian oversight boards are severely limited in their ability to penalize officers.

Police union contracts in Austin, Texas; Columbus, Ohio; and Seattle include all four of these provisions. Many of the municipal contracts also mandate that officers involved in shootings receive paid leave.

I took a closer look at the contract for officers of the Chicago Police Department—which has been under fire for its handling of the Laquan McDonald shooting, among other things—to see how it gives officers “super due process.” In particular, given that Chi-town police have been accused of conducting abusive interrogations, I wanted to see what the contract had to say about the questioning of officers. I also asked David Owens, who has dealt with police misconduct cases as a civil rights attorney at the University of Chicago Law School’s Exoneration Project, to provide commentary on the nine provisions paraphrased below.

Provision 1: An officer should be interrogated while on duty, preferably during daylight hours.

Owens: “Police officers don’t have to care whether you’re not off work or just got off work or just got there. They arrest suspects whenever it’s convenient for them. I’ve seen interrogations start early in the morning or late at night and go all night when somebody should be asleep. So that is a protection not afforded [civilian] criminal suspects who are being interrogated by the police.”

Provision 2: Interrogations may take place only in specific locations: the officer’s usual workplace, the Independent Police Review Authority, the Internal Affairs Division, or another “appropriate” site.

Owens: “Regular suspects have no ability to determine where they will be interrogated. You often see suspects moved from room to room to room at a particular police station. Most of these rooms don’t have clocks, so it’s hard to determine how much time has transpired, which itself is disorienting. Obviously it would be different if the interrogation happened at a suspect’s house or at their place of work or someplace that’s comfortable. But usually a custodial interrogation occurs at the police station—so that’s already sort of a coercive environment. By contrast, the police contract allows officers to be questioned in a place that they’re most comfortable.”

Provision 3: Prior to an interrogation, the officer must be given the names of the person leading the investigation, the primary and secondary interrogators, and anyone else who will be present.

Owens: This seems corrupt. Think about one of the classic things you get when individuals are interrogated: good cop, bad cop. Part of that relies on the fact that you don’t know who this cop is—you don’t know if he’s really a good guy or a bad guy. And that’s a strategy that’s used to, again, disorient you. The police union contract seems to structure the exact opposite. You’ll know who it is, what their rank is, where they’re from. You may know who they’re politically aligned with—if you have friends in common. It gets to a real troubling aspect if you know who these people are, because it makes it seem like this is not an impartial search for the truth—it’s kind of rigged.

Provision 4: Two interrogators may not question an officer simultaneously. The secondary interrogator may speak when invited to by the primary, and should only be asking follow-up questions. The primary interrogator may speak again when the secondary is finished. No more than two investigators may be in the room at the same time.

Owens: “When individuals are being interrogated by police officers, there’s no rule that there be a primary or secondary interrogator. There’s no courtesy—one person talk at a time. There are no rules on what topics anybody can ask about. But you can understand why the police would want that. Because it can be confusing when you have people screaming random questions at you. I’ve seen cases where who interrogates you is shift-dependent. So you may have two or three detectives starting on one shift—they keep you in a room. Those guys sign off, and then two different guys come in. So there can be four, five, six, seven people involved.”

Provision 5: An officer must be given breaks to use the bathroom, eat, make phone calls, and rest during an interrogation. The length of the interrogation must be “reasonable.”

Owens: “There’s no time limit on [civilian] interrogations. Usually, there’s a constitutional thing where if you’re being held and they don’t have evidence, they have to let you go after 48 hours—which sometimes gets pushed to 72. But that’s a really long time. And there’s no requirement about food at your will. There’s no requirement about sleep or phone calls or rest or anything like that. They’re in complete control, and you have very few—if any—rights. In a number of cases, I’ve seen food used as an incentive to elicit an incriminating statement. ‘Look, man—you’ve been here 15 hours and we haven’t given you any food. You want some food? Just tell us what we want to know.'”

Provision 6: Interrogators may not threaten an officer with transfer, dismissal, or other disciplinary action—or offer a reward for providing information.

Owens: “That’s consistent with rules that you would see for average suspects. And this gets to the issues of coercion and voluntary statements. Promises of leniency are supposed to be forbidden. However, this raises a second issue—how do these rules play out? The question becomes, how explicit does an officer have to be for there to be an actual promise of leniency that is forbidden? And the lines get murky. ‘Tell us this information and you can go home.’ ‘Tell us this information and we’ll give you some food.’ ‘Oh—are you worried about getting back to somebody who could be in danger? Give us this information.’ So you see things just short of that all the time that sound like offers and promises that would motivate somebody to act.”

Provision 7: A copy of all statements, written or recorded, made by an officer must be given to the officer within 72 hours of when the statements were made. If he/she is interrogated again during that period, the officer must be given a copy of his previous statements before he is questioned again.

Owens: “You can understand why the police would want that: They can surmount their defense. They can keep their story together. Interrogators try to catch people in lies. If you have a copy of every story that you’ve given, it’s going to be easier to tell that story again and again. That is not at all what you see with any [civilian] criminal defendant. Information asymmetry is one of the things that’s supposed to make the interrogation effective.”

Provision 8: Officers cannot be disciplined for refusing to take a lie detector test, and the results are not admissible in court unless mandated by law or court order. If an officer is required to take the test, the complainant must also take the test. If the complainant refuses, the officer does not have to take the test.

Owens: “That’s a mixed one. In most courts and many proceedings, lie detector tests are not admissible anyway. They’re considered totally unreliable. Joe Blow on the street probably doesn’t know that, but an officer does. And so there’s information asymmetry. The [detectives] say, ‘If you’re telling us that this happened, will you give us a lie detector test?’ And the guy says, ‘Yes.’ And then the officers tell him, ‘Oh, you failed the test.’ And, in fact, the polygraph test becomes a method of eliciting a statement because it provides more pressure. You think you have failed something about the truth. But the officer’s contract sets up the exact opposite. One: You’re going to know about this in advance. Two: You have certain rights about it. And it’s a two-way street. There’s no requirement that regular suspects be allowed to put whoever has implicated them through a polygraph test.”

Provision 9: No photograph of an officer can be made public unless the law requires it.

Owens: “As far as I know, you don’t have any right against the dissemination of any picture taken of you while you’re being interrogated or while you’re in police custody. Booking information is available. You see pictures of arrestees on the news all the time.”

Owens adds that some of the union protections—such as ensuring people are well rested and have the opportunity to take breaks during an interrogation—make perfect sense. “Those are things that would greatly reduce the coercive nature of the environment,” he says. “The problem isn’t that those things shouldn’t apply to people—it’s that they shouldn’t only apply to police officers.” Other provisions, such as delaying the questioning of officers, can hinder the investigation and give the officer more time to craft a plausible lie. “It undermines the things that you would want to help you get the truth,” he says, and “facilitates opportunities to intentionally mislead, or even fabricate versions of the events.”