On a chilly evening last March in Flint, Michigan, LeeAnne Walters was getting ready for bed when she heard her daughter shriek from the bathroom of the family’s two-story clapboard house. She ran upstairs to find 18-year-old Kaylie standing in the shower, staring at a clump of long brown hair that had fallen from her head.

Walters, a 37-year-old mother of four, was alarmed but not surprised—the entire family was losing hair. There had been other strange maladies over the previous few months: The twins, three-year-old Gavin and Garrett, kept breaking out in rashes. Gavin had stopped growing. On several occasions, 14-year-old JD had suffered abdominal pains so severe that Walters took him to the hospital. At one point, all of LeeAnne’s own eyelashes fell out.

The family was suffering from the effects of lead in Flint’s water supply—contamination that will have long-term, irreversible neurological consequences on the city’s children. The exposure has quietly devastated Flint since April 2014, when, in an effort to cut costs, a state-appointed emergency manager switched the city’s water source from Detroit’s water system over to the Flint River.

Elected officials toasted the change with glasses of water, but some longtime residents were skeptical, particularly since Flint-based General Motors had once used the river as a dumping ground. “I thought it was one of those Onion articles,” said Rhonda Kelso, a 52-year-old Flint native. “We already knew the Flint River was toxic waste.”

The lead exposure persisted for 17 months, despite repeated complaints from residents of this majority-black city. It is in no small part thanks to Walters, a no-nonsense stay-at-home mom with a husband in the Navy, that the Flint situation is now a full-blown national scandal complete with a class-action lawsuit, a federal investigation, National Guard troops, and many people—including Bernie Sanders—calling for the resignation of Gov. Rick Snyder. “Without [Walters] we would be nowhere,” Mona Hanna-Attisha, the head of pediatrics at Flint’s Hurley Medical Center, told me. “She’s the crux of all of this.”

It was the summer of 2014 when Walters first realized something was very wrong: Each time she bathed the three-year-olds, they would break out in tiny red bumps. Sometimes, when Gavin had soaked in the tub for a while, scaly red skin would form across his chest at the water line. That November, after brown water started flowing from her taps, Walters decided it was time to stock up on bottled water.

The family developed a routine: For toothbrushing, a gallon of water was left by the bathroom sink. Crates of water for drinking and cooking crowded the kitchen. The adults and teenagers showered whenever possible at friends’ houses outside Flint; when they had to do it at home, they flushed out the taps first and limited showers to five minutes. Gavin and Garrett got weekly baths in bottled water and sponge baths with baby wipes on the other days. Slowly, the acute symptoms began to wane.

In January 2015, Flint officials sent out a notice declaring that the city’s water contained high levels of trihalomethanes, the byproduct of a disinfectant used to treat the water. Over time, these chemicals can cause liver, kidney, and nervous system problems. The advisory warned that sick and elderly people might be at an increased risk, but it said the water was otherwise safe to drink. “That was when I went to my first city council meeting,” Walters told me.

She wasn’t the only one. Flint residents showed up in droves, many complaining of stinky, tainted water coming out of their taps. They cited symptoms ranging from hair loss and rashes to memory and vision loss.

The problem was exacerbated by a lack of alternatives. Flint is one of America’s poorest cities, with 41 percent of its residents living in poverty. Many couldn’t afford bottled water or make the trek to obtain it—the city of 100,000 only has one major grocery store, on the far side of town. Kelso, a stroke survivor who lives with her 12-year-old daughter, relied on relatives to take her on water runs outside the city. “Sometimes there’s no water,” she said. “People who can buy water, they buy it up.”

Throughout most of 2015, the city and state maintained there was nothing to worry about. “I want to assure everyone that the city is sensitive to the public’s concerns,” Dayne Walling, then Flint’s mayor, declared at a press conference that January. “The city water is safe to drink. My family and I drink it and use it every day.” Walters and others, dubbing themselves “water warriors,” began staging regular protests outside City Hall.

In February, at Walters’ urging, the city sent an employee to test the water coming from her taps. A few days later, she received a voice mail from the water department, warning her to keep her kids away from the water. “You know when somebody calls and you can just hear the panic in their voice? It was that,” Walters recalled. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, there’s no safe level of lead in drinking water. The maximum concentration allowed by law is 15 parts per billion. The Walters’ tap water measured nearly 400 ppb.

Walters began compulsively researching lead exposure. She learned, to her horror, that the element has a particularly dramatic effect on young children, with long-term symptoms that can include a lower IQ, shortened attention span, and increases in violence and antisocial behavior—not to mention effects on reproductive and other organs. Studies also have tied higher lead levels to significantly increased rates of crime and teen pregnancy. The neurological and behavioral effects, notes the World Health Organization, “are believed to be irreversible.”

Walters rushed to get her children tested, and the results confirmed her worst fears: All four kids had been exposed to lead, and Gavin, who already had immune system problems, had bona fide lead poisoning, which put him at far greater risk. “I was hysterical,” said Walters. “At first, it was self-blame. And then there’s that anger: How are they letting them do this?”

The city’s initial response was to hook up a garden hose to her neighbor’s house to provide water for her family—officials claimed that the problem probably had to do with the Walters’ own plumbing. Just days after Walters got the results of her children’s blood tests, Gov. Snyder’s office assured residents that “Flint’s water system is producing water that meets all state and federal standards.” (Representatives from the city and the state’s Department of Environmental Quality declined to comment for this story.)

Walters, who is trained as a medical assistant, began staying up late at night to go through reams of Flint water quality reports. She learned that Flint River water is more corrosive than Detroit tap water, and she wondered why Flint hadn’t applied standard chemicals—known as corrosion controls—to prevent the leaching of metal from its aging pipes into the water supply. This treatment is critical in a city such as Flint, where half of households are connected to a lead water line. She also didn’t understand why the city employee who tested her water ran the tap for several minutes before taking a sample. If something were building up in her pipes, wouldn’t flushing it out understate the results?

Frustrated with the city’s lackadaisical response, Walters called Miguel Del Toral, a manager at the EPA’s Midwest water division, last March. She explained that Flint didn’t appear to be using corrosion controls and that it was flushing pipes before conducting lead tests. She also emailed him water quality reports for the previous year. Del Toral was floored. “From a technical standpoint, there’s just no justification for the way Flint is conducting its tests,” he later told the American Civil Liberties Union. “Any credible scientist will tell you [the city’s] method is not the way to catch worst-case conditions.”

By contacting Del Toral, Walters unwittingly unleashed a chain of investigations. He introduced her to Marc Edwards, an expert in lead corrosion at Virginia Tech who instructed her to collect new samples from her house without pre-flushing the pipes. In those samples, Edwards found lead concentrations of 13,200 ppb—more than twice the level the EPA classifies as hazardous waste. “At that point, you do not just have smoke, you have a three-alarm fire and should respond immediately,” he told the Detroit News.

Edwards put together a team to conduct field tests in Flint and to seek data from the city and the state. Del Toral, meanwhile, relayed his concerns to the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality, setting off a slow, bureaucratic back-and-forth between the state and the EPA. News that that the Virginia Tech team and the EPA were looking into the matter alarmed Mona Hanna-Attisha, the pediatrician at Hurley Medical Center. She began researching the blood lead levels of Flint’s youngest children before and after the change of water supply, comparing them with children living elsewhere in Genesee County.

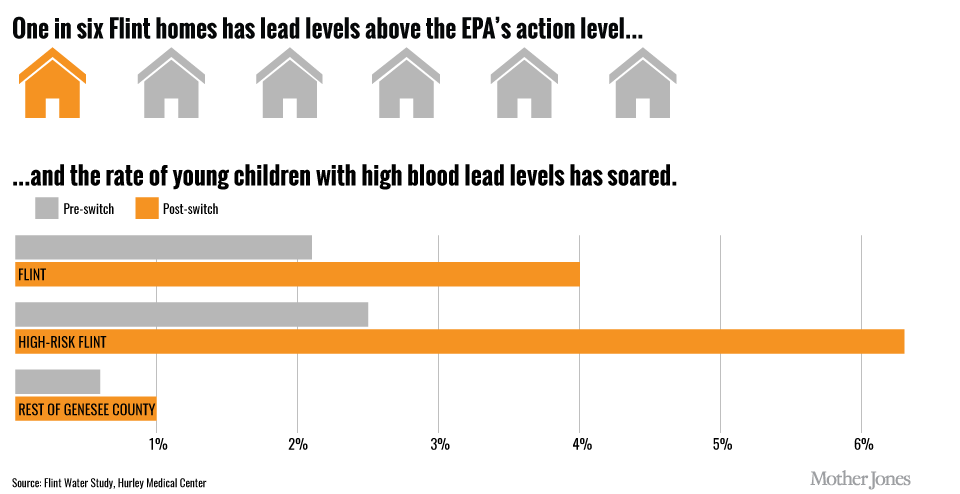

The results from both investigations came back last September. Edwards’ tests suggested that one in six Flint homes had lead water levels exceeding the EPA’s safety threshold. Hanna-Attisha found that the rate of children younger than five with elevated lead concentrations in their blood had doubled—and in some areas, tripled—following the switch to Flint River water. The effect, she told CNN, would be analogous to “drinking through lead-painted straws.”

The day after Hanna-Attisha’s findings came out, the city released a lead advisory. State officials remained skeptical, insisting that the results were incorrect and that Flint’s water met federal standards. But by mid-October, after weeks of deliberations and lots of bad press, Gov. Snyder ordered that Flint’s water supply be switched back to the Detroit system. “It recently has become clear that our drinking-water program staff made a mistake while working with the city of Flint,” said Dan Wyant, the state’s Environmental Quality Director, who resigned not long after. “Simply stated, staff employed a federal protocol they believed was appropriate, and it was not.”

Earlier this month, Snyder deployed National Guard troops to work alongside Red Cross volunteers, delivering bottled water, water filters, and lead-testing kits to Flint residents—who still can’t drink from the tap thanks to the corroded lead pipes. On Saturday, President Barack Obama declared a state of emergency in Flint, entitling the city to federal disaster relief funds. Several residents, including Rhonda Kelso, have joined together in a class-action suit targeting city and state officials, including ex-Mayor Walling and Gov. Snyder. The US Attorney’s Office for Michigan’s Eastern District has launched its own investigation into the crisis.

The Walters no longer live in Flint—they moved to Virginia in October, partly in response to the contamination. But the water issue continues to consume LeeAnne, who regularly Skypes into meetings and fields calls with politicians and activists. She recently traveled to Washington, DC, to meet with EPA officials. Other Flint moms seek her out for advice; one telephoned after tests found that her 15-year-old daughter had the liver function of a 75-year-old. Walters won’t let her family drink Virginia tap water until she’s had it tested—or eat at a restaurant without reviewing its health reports in advance.

The hardest thing, she says, is not knowing how the lead exposure will affect her kids in the long term. Gavin was the “party animal” of the twins, but lately he’s lost his appetite and sleeps more. At five, he weighs a mere 35 pounds to Garrett’s 53, and he mispronounces words that he could once handle. Garrett was recently diagnosed with ADHD. Both boys continue to ask, when handed a cup of water, whether it is “good water or bad water.”

When I asked Walters what she makes of all the national attention, she paused. “Everybody’s been asking, ‘How do you feel now that people are finally listening? Do you feel satisfied?'”

Then she was crying. “Every time I get a call from another mother whose child is sick,” she managed, “it doesn’t feel like a victory.”

Correction: An earlier version misstated the number of grocery stores in Flint.