<a href="http://www.nps.gov/hstr/learn/news/index.htm">Truman Library</a>

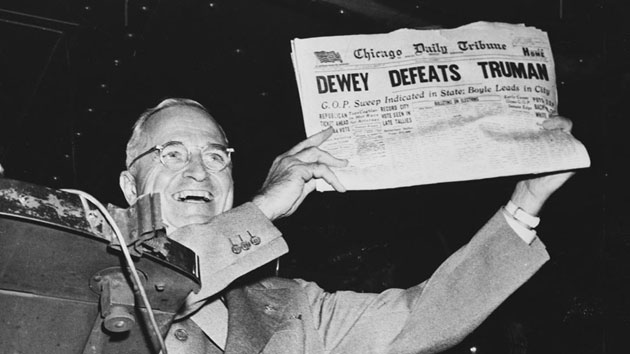

The first candidate to use one of the most abused clichés in electoral politics at least had the facts on his side. Just before 5 p.m. on October 11, 1948, President Harry Truman pulled into the train station in Willard, Ohio, and addressed the crowd from the rear platform. In a brief speech that lasted no longer than 12 minutes, he accused his Republican challenger, New York Gov. Thomas Dewey, of obsessing over public-opinion surveys, and then made a historic prediction. “I think he is going to get a shock on the second of November,” Truman predicted. “He is going to get the results of one big poll that counts—that is the voice of the American people speaking at the ballot box.”

And good for him. Four years after Gallup’s preference for Republican candidates prompted congressional hearings, the preeminent polling firm predicted Dewey would win by five points. Truman won by 2 million votes. You’ve all seen the photo.

As candidates dealt with the increasing omnipresence of polls, Truman’s mantra became a handy crutch. At first, the historical allusion was explicit. “In one respect I’m like Harry Truman about polls,” Vice President Richard Nixon told the New York Times in 1959. “We share that in common, plus the fact that we both play the piano. I believe the only poll that counts is that on election day.” As he prepared to face Sen. John F. Kennedy the next year, he told Democrats, “I can agree with the distinguished member of your party, Mr. Truman, when he said that the only poll that counts is the one on election day.”

Nixon’s habitual usage of the term helped usher it into the mainstream. In 1972, his daughter Tricia declared that “the only poll that really counts is the vote on election day.” Four years later, Tricky Dick sent a private note of encouragement to his successor, President Gerald Ford: “Keep that confident, fighting spirit—and the only poll that matters will come out alright on November 2.” Within two years, yet another president, Jimmy Carter, was quoting from the Book of Harry: “Look, the only poll that matters in politics is the poll that the people conduct on election day.”

By 1980, when Carter was still holding out hope for the one true poll, the Times felt comfortable calling the use of the cliché a classic gesture of “politicians running behind.” It has even traveled across the pond (as a corollary to the very British phrase, “Every jockey knows the fence that counts is the last one”), and found an ironic second life among college football fans.

The problem now is that it’s no longer true, for wildly divergent reasons. The polls have been all over the place in 2016, and they’re only getting worse because, as Jill Lepore explained in the New Yorker, the pool of people who participate in them is becoming smaller and less representative. But at the same time, the polls matter more than ever. For the first time in a party-nominating contest, they were used to split the Republican candidate field into two tiers of debates—more than a year before election day.

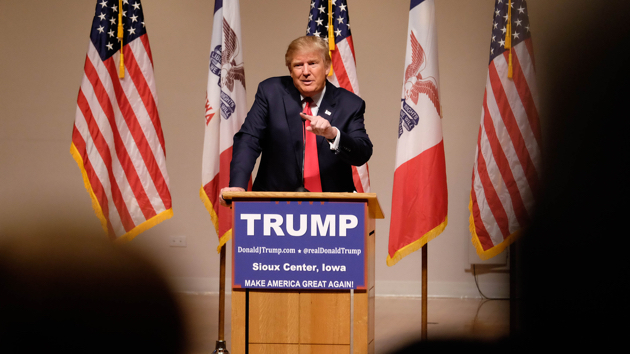

If the cliché is truly dead (it may be indestructible), then Donald Trump killed it. In a rebuke to the Nixons and Trumans—and basically everyone else—who came before him, he has decided that polls are, in fact, fantastic. He can rattle off the latest results off the top of his head; at the most recent debate, in South Carolina, he even corrected a moderator who misstated the size of his lead. And it’s working. The effect has been to turn the polling industry into a political perpetual-motion machine; poll numbers beget media coverage about poll numbers, which beget even higher poll numbers.

After all this, maybe there’s only one way this story can end:

Great @NewYorker cover. “Trump Defeats Kanye” pic.twitter.com/Xe0cbHHN4N

— Eric Grant (@ericgrant) September 12, 2015