Photo by Jack Miller/Image courtesy of Diane Ravitch

Last time I called Diane Ravitch, our country’s leading education historian and one of the most vocal voices in education reform, she was on another call with the producers of The Daily Show. It was 2011, and The Daily Show was about to air a segment about the low salaries that teachers earn and Wisconsin’s Republican Gov. Scott Walker’s intentions to cut teachers pay and reduce workers’ collective bargaining powers. The producers were calling to invite Ravitch to come on the show to talk to Jon Stewart about teachers and education reform.

At the time, reducing the power of teachers’ unions, promoting charter schools, and using standardized test scores to weed out “bad teachers” and close “failing schools” had become the most popular silver bullets of the education reform movement. Michelle Rhee, the former chief of DC schools, had become the most prominent public face of these kinds of education reforms—ones that Ravitch was critiquing on The Daily Show. Rhee had come out in support of Walker’s policies.

In 2010, Newsweek published a cover story called “The Key to Saving American Education: We must fire bad teachers.” That same year, on The Oprah Winfrey Show, Rhee announced that she was forming a national organization called Students First to promote her ideology among state policymakers. In 2013, Students First came out with “report cards” that graded each state’s performance against the reform movement’s education agenda. The report cards, like the policies Rhee and her allies pushed, received frequent—and fairly positive—media coverage.

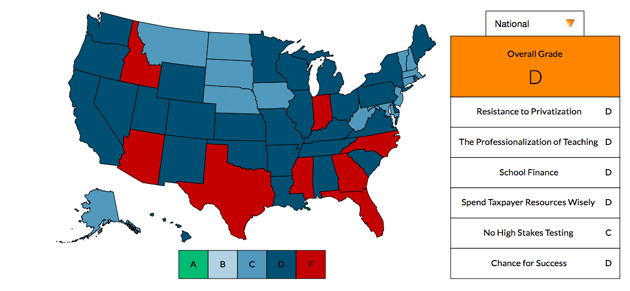

When commentators and reporters needed a countervoice, Ravitch became the go-to progressive critic. She was not the only prominent academic who questioned the attacks on teachers, but she was the most vocal, thanks in part to her media savvy and punchy writing—and her 125,000 Twitter followers. In 2013, Ravitch and her allies launched the Network for Public Education, a nonprofit advocacy group that aims to counter what she calls the “right-wing propaganda.” Her organization pushed forward its own brand of education reform policies: more equitable school funding, early childhood education, integrated classrooms, reduced use of testing, and stronger professional development for teachers. This Tuesday, the Network for Public Education published its own version of state report cards, rating every state using 29 factors, such as policies on testing, school finance, teacher pay and rates of attrition, mentoring programs for teachers, and controls on charter school expansion, among others. No states received an overall grade of “A,” but Iowa, Nebraska, and Vermont got the highest grades. New Jersey was the only state to get an “A” for equitable funding. Alabama, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, and Vermont all scored high for rejecting the use of tests to punish teachers or students.

Things are not going so well for the proponents of test-based and market-driven education reforms, Ravitch wrote on her blog a few months before her group released its report cards. She then went on to cite research—much of it included in the report cards—showing the failed promises of Rhee-style reforms: Charter schools on average don’t produce higher test scores than public schools; online charter schools perform much worse than public schools; teacher evaluations that include test scores haven’t helped to “weed out the bad teachers” and identify the best; achievement gaps haven’t changed. “Michelle Rhee has stepped away from the national stage, into apparent obscurity,” Ravitch wrote, “even though her organization continues to fund right-wing anti-public school state-level candidates.”

My second call to Ravitch was this past Tuesday, to ask her about the organization’s report cards, and the surprises her team found. Ravitch was joined by Carol Burris, the executive director of Network for Public Education.

Mother Jones: Why are these new state report cards important?

Diane Ravitch: There were all of these state reports coming out from right-wing groups like Students First and the American Legislative Exchange Council arguing that the definition of success is getting rid of public education and taking away any right that teachers might have. These create a climate when there is report card after report card agreeing that the future should be privately managed [charter] schools. There is nobody on the other side other than the unions, which are immediately discredited. There need to be two sides to the debate. Right now [the education conversation] is presented as what Students First is promoting is all that works.

We felt it was important to set up this other criteria and show how effective school systems operate: They are adequately funded, have preschools; they make sure that their teachers are professionals, and they don’t give away their authority. This is how the best nations in the world operate. They don’t operate through vouchers and charters.

MJ: Why is New Jersey the only state that got an ‘A’ in “School Finance”?

DR: New Jersey had court rulings that required the state to adjust its school funding. They have done a lot of redistribution to make sure that poor districts get more resources. What they still haven’t done anything about is segregation. Today they have a group of districts—called the Abbott districts [low-income districts that receive higher levels of funding per student than the average spending in the state]—that get a lot of money but are intensely segregated. These schools remain in high poverty and segregated areas, like Newark.

MJ: How is New Jersey doing with improving kids’ test scores and closing the gap between black, Latino, and white students?

DR: If you look at National Assessment of Educational Progress [NAEP] scores in New Jersey, it’s one of the highest-scoring states in the country, even though it has very poor, low-performing districts. When it comes to achievement gaps, there is nothing to brag about, but it is doing much better than Washington, DC. In 2008, we had a Time magazine story with Michelle Rhee on the cover telling us that DC was going to lead the way in how education reform should be done, but DC continues to have an achievement gap that’s twice that of other cities and twice that of New Jersey.

MJ: Your report says the gap in spending per student in poor schools compared to rich schools has grown 44 percent in the last decade. Why?

DR: One important reason is that the federal policy has tilted completely toward testing and accountability and away from equity. The Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 was all about equity and equitable resources for low-income students, and then in the 1990s that began to change. In DC, policymakers think that if we can only have high enough standards, tough enough tests, and hold people accountable, we can close the achievement gap. And it hasn’t happened. Yet the new law, the Every Student Succeeds Act, is based on the same test-based and market-driven framework and ideology, except it lets the states do it.

MJ: Research consistently shows that when teachers are allowed to learn on their jobs and have a voice in decision-making processes, kids’ achievement improves. Typically, the presence of such practices is measured as the hours teachers are paid to collaborate and plan. That wasn’t in your report. Why?

Carol Burris: There are so many factors we wished we could have included, but couldn’t. Francesca Lopez, the researcher at the University of Arizona who worked with us, was able to get limited data from the National Center of Educational Statistics on this issue. But once we put the report cards out, we hope that people will suggest what other factors we should be including. In general, it was a challenge for us to find recent data and cross-national sources for everything.

MJ: Your report cards also don’t include any student test scores or graduation or college acceptance rates. Why is that?

CB: The point of the report card is not to judge individual schools or even to judge kids. We wanted to look at factors that states can control through policies. If you change specific research-based practices that we identified, then the outcomes that you can expect would be higher test scores. But to use something like NAEP standardized scores without proper controls for poverty, it didn’t make sense to us. We really wanted to look at the “inputs” of educational systems, such as funding or class size, that research shows increase achievement.

MJ: What impact do you hope to have?

CB: We hope the readers will think deeply about the path that we are on and engage in grassroots campaigns at the district or state house level. We need to make sure that policymakers who are truly committed to public schools move beyond popular silver bullets that have failed in the last decade and pay attention to policies that are actually effective.