Michael Mechanic

Last night, the FBI, saying that it may be able to crack an iPhone without Apple’s help, convinced a federal judge to delay the trial over its encryption dispute with the tech company. In February, you may recall, US magistrate judge Sheri Pym ruled that Apple had to help the FBI access data from a phone used by one of the San Bernadino shooters. Apple refused, arguing that it would have to invent software that amounts to a master key for iPhones—software that doesn’t exist for the explicit reason that it would put the privacy of millions of iPhone users at risk. The FBI now has two weeks to determine whether its new method is viable. If it is, the whole trial could be moot.

That would be a mixed blessing for racial justice activists, some of them affiliated with Black Lives Matter, who recently wrote to Judge Pym and laid out some reasons she should rule against the FBI. The letter—one of dozens sent by Apple supporters—cited the FBI’s history of spying on civil rights organizers and shared some of the signatories’ personal experiences with government overreach.

“One need only look to the days of J. Edgar Hoover and wiretapping of Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. to recognize the FBI has not always respected the right to privacy for groups it did not agree with,” they wrote. (Targeted surveillance of civil rights leaders was also a focus of a recent PBS documentary on the Black Panther Party.) Nor is this sort of thing ancient history, they argued: “Many of us, as civil rights advocates, have become targets of government surveillance for no reason beyond our advocacy or provision of social services for the underrepresented.”

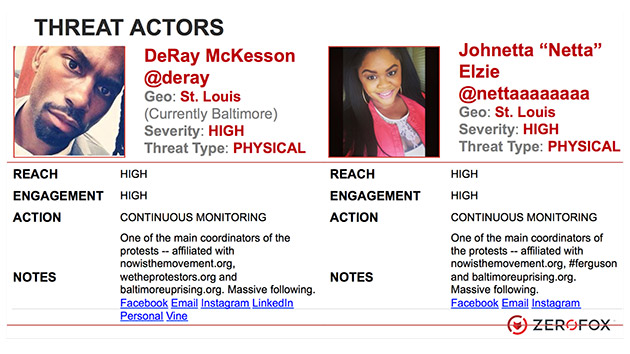

Black Lives Matter organizers have good reason to be concerned. Last summer, I reported that a Baltimore cyber-security firm had identified prominent Ferguson organizer (and Baltimore mayoral candidate) Deray McKesson as a “threat actor” who needed “continuous monitoring” to ensure public safety. The firm—Zero Fox—briefed members of an FBI intelligence partnership program about the data it had collected on Freddie Gray protest organizers. It later passed the information along to Baltimore city officials.

Department of Homeland Security emails, meanwhile, have indicated that Homeland tracked the movements of protesters and attendees of a black cultural event in Washington, DC, last spring. Emails from New York City’s Metropolitan Transit Authority and the Metro-North Railroad showed that undercover police officers monitored the activities of known organizers at Grand Central Station police brutality protests. The monitoring was part of a joint surveillance effort by MTA counter-terrorism agents and NYPD intelligence officers. (There are also well-documented instances of authorities spying on Occupy Wall Street activists.)

In December 2014, Chicago activists, citing a leaked police radio transmission—alleged that city police used a surveillance device called a Stingray to intercept their texts and phone calls during protests over the death of Eric Garner. The device, designed by military and space technology giant Harris Corporation, forces all cell phones within a given radius to connect to it, reroutes communications through the Stingray, and allows officers to read texts and listen to phone calls—as well as track a phone’s location. (According to the ACLU, at least 63 law enforcement agencies in 21 states use Stingrays in police work—frequently without a warrant—and that’s probably an underestimate, since departments must sign agreements saying they will not disclose their use of the device.)

In addition to the official reports, several prominent Black Lives organizers in Baltimore, New York City, and Ferguson, Missouri, shared anecdotes of being followed and/or harassed by law enforcement even when they weren’t protesting. One activist told me how a National Guard humvee had tailed her home one day in 2014 during the Ferguson unrest, matching her diversions turn for turn. Another organizer was greeted by dozens of officers during a benign trip to a Ferguson-area Wal-Mart, despite having never made public where she was going.

In light of the history and their own personal experiences, many activists have been taking extra precautions. “We know that lawful democratic activism is being monitored illegally without a warrant,” says Malkia Cyril, director of the Center for Media Justice in Oakland and a signatory on the Apple-FBI letter. “In response, we are using encrypted technologies so that we can exercise our democratic First and Fourth Amendment rights.” Asked whether she believes the FBI’s promises to use any software Apple creates to break into the San Bernadino phone only, Cyril responds: “Absolutely not.”

“I don’t think it’s any secret that activists are using encryption methods,” says Lawrence Grandpre, an organizer with Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle in Baltimore. Grandpre says he and others used an encrypted texting app to communicate during the Freddie Gray protests. He declined to name the app, but said it assigns a PIN to each phone that has been approved to access messages sent within a particular group of people. If an unapproved device tries to receive a message, the app notifies the sender and blocks the message from being sent. Grandpre says he received these notifications during the Freddie Gray protests: “Multiple times we couldn’t send text messages because the program said there’s a possibility of interception.”

Cyril says “all of the activists I know” use a texting and call-encryption app called Signal to communicate, and that the implication of a court verdict in favor of the FBI would be increased surveillance of the civil rights community. “It’s unprecedented for a tech company—for any company—to be compelled in this way,” Cyril says.

Apple has prepared for an epic fight. But if the FBI is able to crack an iPhone without a key, the BLM crowd will have one more thing to worry about. As Cyril put it in a tweet this past February, “In the context of white supremacy and police violence, Black people need encryption.”