Democratic presidential hopeful Sen. Bernie Sanders meets with supporters at a campaign stop at a Navajo casino in Arizona. Ricardo Arduengo/AP

On Tuesday night, the long lines of Arizona primary voters highlighted the potentially disastrous fallout from a 2013 Supreme Court ruling that gutted the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The specter of a new disenfranchisement controversy was all too familiar for a group of people who have been fighting for their right to vote in Arizona and much of the West for years: Native Americans. “What’s happening in Indian Country is reflective of what’s happening nationwide,” says Daniel McCool, political science professor at the University of Utah and co-author of the book Native Vote.

Earlier this month, Indian Country Today Media Network reported that Native American and Alaska Natives have flagged voting-related problems in 17 states, via litigation or tribal diplomacy with local officials. For example, in Alaska—which will hold its Democratic caucuses Saturday—Alaska Natives scored a victory in September 2014, when a federal judge concluded that state election officials violated the Voting Rights Act when they failed to translate voting materials for Alaska Natives in rural sections of the state. After nine months of talks, they reached a settlement to get election pamphlets translated into six dialects of Yup’ik and Gwich’in through 2020, granting them language assistance ahead of the caucuses this weekend.

Meanwhile, congressional efforts to protect voting rights for Native Americans and Alaska Natives have come to a halt. Last July, Sen. Jon Tester (D-Mont.) announced a bill that would prevent states from moving polling places to inconvenient locations, banishing in-person voting on reservations, and altering early voting locations. The bill, inspired by a voting access case in Montana that compelled three counties to open satellite offices on reservations, has stalled in the Senate Judiciary Committee.

Here are a few other cases to keep in mind:

Poor Bear v. Jackson County: In September 2014, members of the Oglala Sioux Tribe from the Pine Ridge Reservation filed a lawsuit against Jackson County, South Dakota, alleging that county officials refused to create a satellite office where Sioux residents could register and file in-person absentee ballots. For tribal citizens, the closest place to submit their absentee ballots is the county auditor’s office in Kadoka, a town that’s 95 percent white and roughly 27 miles away. (Native Americans must travel twice as far as white residents in the county to submit ballots in person, according to the lawsuit.) Voters can also submit absentee ballots by mail, but they have to submit an affidavit to prove their identity if they lack a tribal photo ID card, a potential hardship for Native American voters.

The county commission declined to approve the office because “it believed funding was not available,” despite a Help America Vote Act plan that allowed the county to use state funds to create the office. After residents filed for a preliminary injunction, the commission agreed to open a temporary satellite voting office in the run-up to Election Day 2014. Last November, in an agreement with South Dakota’s secretary of state, the Jackson County Commission approved a satellite site through 2023.

Brakebill v. Jaeger: In January, seven members of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians filed a lawsuit against North Dakota State Secretary Alvin Jaeger, alleging that the strict requirements under the state’s voter ID law imposed a discriminatory burden on Native Americans. When the state enacted House Bill 1332 in April 2013, it limited the forms of permissible identification at voting booths, required forms of identification to display the voter’s home address and date of birth, and eliminated a provision that allowed voters to use a voucher or affidavit if they failed to bring an ID. The lawsuit alleges that the bill “disenfranchised and imposed significant barriers for qualified Native American voters by establishing strict voter ID and residence requirements.”

According to the lawsuit, Native Americans in North Dakota have to travel an average of nearly 30 miles to obtain a driver’s license. The lawsuit also claims that many Native Americans lack tribal government IDs with residential addresses, which is an alternative form of ID under state law. In February, Jaeger tried to get the case tossed out, arguing that the voter ID law was constitutional. The judge has yet to decide.

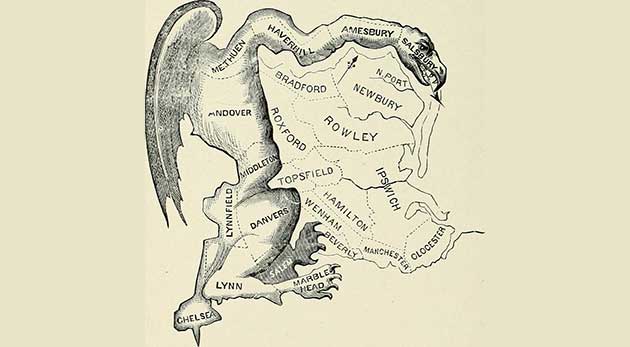

Navajo Nation Human Rights Commission v. San Juan County: Less than two years ago, prospective Navajo Nation voters in San Juan County, Utah—where Native Americans are nearly 47 percent of the population—had to travel an average of two hours to submit a ballot in the predominantly white city of Monticello, without access to reliable public transportation. That’s because in 2014, according to a lawsuit filed by the American Civil Liberties Union and others in late February, the county closed polling places and switched over to mail-in ballots, placing a “disproportionately severe burden” on Navajo residents. The county has yet to respond in court to the case.

It wasn’t the first time San Juan County has been sued for violating the Voting Rights Act. In fact, the Navajo Nation claimed in a previous lawsuit that the county commission “relied on race” when it decided not to change the boundary lines for a largely Native American district in 2011, three decades after they were initially drawn. In February, US District Judge Robert Shelby ordered the county to redraw its election district lines after he ruled that its current boundaries, which were set after a settlement with the Justice Department in the 1980s, were unconstitutional.