<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-51633604.html?src=download_history">Pushkin</a>/Shutterstock

David Erlich never thought of himself as a kingmaker. He chairs the Alameda County Republican Party, a lonely redoubt of conservatism situated on the east side of San Francisco Bay amid ultra-lefty Berkeley and Oakland. Served by Barbara Lee, arguably the nation’s most liberal member of Congress, the district’s 400,000 registered voters include fewer than 30,000 Republicans. “We have not been relevant,” Erlich concedes, putting it lightly.

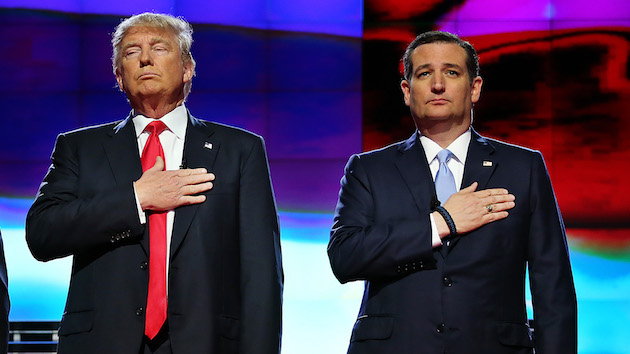

But that’s about to change. With Republicans fiercely divided between Donald Trump and Ted Cruz so late into primary season, the race for the GOP’s presidential nomination will—for the first time in at least a half century—likely hinge on the June 7 vote in deep-blue California. “It’s exciting,” says Erlich, an electrician and enthusiastic Trump supporter. “We can probably make it cool to be Republican again.”

California’s GOP primary, like its Republicans, is deeply idiosyncratic: Open only to registered party members, the balloting does not take into account the GOP’s uneven support across the state. Each district confers exactly three delegates in a winner-take-all election, regardless of how many Republicans actually live there. So the district that represents 166,000 Republicans in conservative Orange County, for example, is worth as many delegates as the one representing San Francisco or Marin or Berkeley—which have fewer than 150,000 Republicans combined. This means the Republicans whose votes matter most are the ones living in the most liberal districts—like Erlich’s.

“The trick in this primary is not to reach the wide audience,” notes GOP political consultant Bill Whalen, former director of public affairs for Republican Gov. Pete Wilson. “It is to reach smaller, specific targets, especially in those congressional districts with fewer Republicans, where a smaller number of Republicans will flip the district in your favor.”

This has had the strange effect of empowering local GOP officials—people who’ve often labored for years in obscurity, running quixotic candidates against Nancy Pelosi or denouncing climate-change laws in Santa Cruz. Their efforts may have universally failed, but they now possess valuable connections with potential volunteers and local voters. “If you are someone who has spent years toiling in the Republican vineyard, your experience is now at a premium for the three candidates,” Whalen says. “This is a new world, literally, for California Republicans.”

At the storefront office of the Alameda County Republican Party, located along a San Leandro freeway next to an Aikido studio, I find Erlich in high spirits. Marco Rubio has just dropped out of the races after losing his home state of Florida to Trump. Erlich gleefully rips a Rubio campaign sign off the wall, where it had hung next to a poster of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., and throws it in the trash. “I guess this one we can take down,” he says. “Thank God.”

Living in a county that gave birth to the free speech movement and the Black Panthers hasn’t necessarily made its Republicans more politically moderate. Conspicuously lacking from among the dozens of photos of GOP heroes on the walls of Erlich’s office is former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, the last California Republican to win statewide office. “He gave birth to AB 32!” the state’s climate change law, Erlich snorts. “Why are you going to run as a Republican if you vote for policies that are totally against it? If you give up your principles, that is what I call corruption of the heart.”

Erlich’s deep conservatism hasn’t won him many friends in these parts. When he ran for State Assembly in 2014 against Democrat Rob Bonta, he raised $5,000 to Bonta’s $480,000. He campaigned in Oakland’s predominately Latino Fruitvale district, where he told people that welfare and subsidized housing were just designed for “keeping them on the plantation.” That one went over well compared with the time he described Oakland city council meetings as “like a zoo,” prompting accusations of racism. His detractors have occasionally done more than denounce him. “We had a broken window once,” he told me, “but that is what insurance is for.”

Still, Erlich’s views seem pretty typical of fellow Republicans in Alameda County. In the 2014 gubernatorial primary, a majority of local party members joined him in backing Tim Donnelly, an anti-immigration tea party candidate who remained on probation for the duration of the campaign after pleading guilty in 2012 to misdemeanor gun charges stemming from his attempt to pass through airport security in Ontario with a loaded weapon. Statewide, Donnelly narrowly lost to moderate Republican Neel Kashkari, a former Treasury Department official who’d voted for President Barack Obama in 2008; Kashkari advanced to the general election, where he lost to Democratic incumbent Jerry Brown.

The failure of Donnelly, who was a member of the anti-immigration Minuteman Project, suggests that Trump could face headwinds in California. But it also shows why counties such as Alameda will be crucial for him. According to an analysis by the University of Virginia’s Center for Politics, Trump will likely have to win the state’s popular vote along with 32 of its 53 congressional districts to amass enough delegates to lock up the nomination. So while Trump leads Cruz by seven points in the most recent state poll, victory will also require building a ground game in potentially sympathetic districts. “They are going to have to go out and find would-be Trump voters and convince them that they’ve got to register for the cause,” Whalen says. “And that is not the kind of micro-organization that he has been known for.”

Erlich, for one, still hasn’t heard from the Trump campaign. In fact, none of the state and local party officials I interviewed even knew where to send would-be Trump volunteers.

Cruz, meanwhile, has spent months accumulating campaigners and connections in the Golden State. Ron Nehring, his national spokesman and California campaign director, previously ran for state lieutenant governor and served as the chairman of the California GOP. “California, here we come,” he wrote recently on Flashreport, the state’s leading Republican blog. “Every single supporter of Marco Rubio, John Kaisch, or any other past candidate for president are welcome on the Cruz campaign.”

Yet Erlich believes it’s precisely this sort of rhetoric that will spell doom for Cruz. By flinging open his campaign to moderates and their corporate money, Cruz will alienate voters who want a true conservative who is willing to buck the establishment. “We have a litmus test when Republicans come in,” Erlich declares as he walks up to a two-foot-tall elephant statue. Pulling off its raised trunk to reveal a horn beneath, he asks, “Are you a Republican, or are you a RINO?”

Of course, many California conservatives wouldn’t admit to being either. “Millennials building their careers in San Francisco just don’t want any reference to the fact that they are Republican,” says Christine Hughes, chair of the San Francisco Republican Party, who supports Kasich.

So does she agree with Erlich that the upcoming primary might make California Republicanism cool again? “Maybe, maybe not,” Hughes says. “The good news for us is, I am going to be able to register more Republicans.”