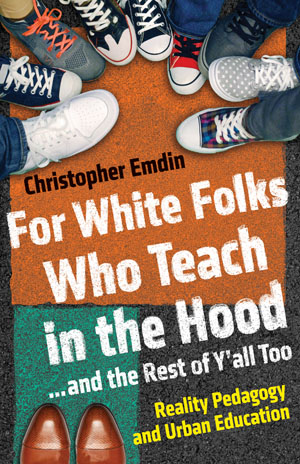

Photo by Ryan Lash

When Chris Emdin, now an associate professor of math, science, and technology at Columbia University, was a senior in a Brooklyn high school, most of his teachers were quick to punish him for things like doing a little celebratory dance in his chair after he nailed a teacher’s question or standing up and stretching without permission in the middle of a long assignment. Emdin’s teachers often called him a “disobedient” and “troubled” student. Emdin badly wanted to go to college, he writes in his new book, For White Folks Who Teach in the Hood…and The Rest of Y’all Too, so he learned to suppress his “unabashed urbanness,” or what he describes as his tendency to be loud, conspicuous, and prone to question authority. “I became conditioned to be a ‘proper student’ and began to lose value for pieces of myself that previously defined me.”

Years later, when Emdin started teaching in a predominantly black high school, an older teacher told him, “You look too much like them, and they won’t take you seriously. Hold your ground, and don’t smile till November.'” Emdin followed the advice. But then, during his first year of teaching, he realized he had become the same authoritarian he resented when he was in high school. Like his fellow teachers, Emdin viewed students who spoke too loudly, laughed without permission, or exuded too much confidence as “problem students.” Kids who were demure, quiet, and followed the rules were viewed as “teachable.”

Researchers have found that such mental sorting is commonplace in American classrooms and has huge impact on a student’s ability to succeed. When teachers think a student is “teachable,” he or she supports that student in hundreds of invisible ways: by giving them more time to answer questions, or through visual cues such as nodding and smiling. What’s more, new research found that when a white teacher and a black teacher evaluate the same black student, white teachers are almost 40 percent less likely to think the black student will graduate high school. That same bias often translates into a white teacher being less rigorous with the student and more prone to discipline him or her.

Emdin and a few other scholars are now trying to focus policymakers’ attention on classroom interventions that reduce such racial biases—a focus that has been lacking in the mainstream public debate about school reforms. Emdin’s new book—based on his research, observations, and work with other educators in traditional, charter, and private schools over the last decade—is full of insights and practical tools that can often be foreign to white teachers who work with black and Latino students. He argues teachers need to be exposed to a broader range of cultural norms, rules for engagement, and ways to express knowledge.

For example, Emdin once invited a Teach for America school leader—who struggled to engage his students and blamed their inability to pay attention—to a black church in Harlem. Emdin wanted to show the young teacher how black preachers keep people of all ages enthralled in their sermons, which are often three hours long. The preacher was clearly in charge, Emdin pointed out, but he also allowed his congregation to participate and guide the service. The preacher was engaged in a conversation with his audience, paying attention to how people responded and often improvising when something wasn’t working.

Emdin took other teachers to barber shops and hip-hop concerts to help them get to know the communities where their students live. If urban educators can learn to appreciate these diverse forms of intellectual expression as valuable tools, Emdin argues, their teaching will improve—no sweeping federal policy changes, new tests, or extra funding required.

We caught up with Emdin during his book tour to talk about the changes he’d most like see in urban schools.

Mother Jones: In your book, you often compare strict discipline tactics practiced in classrooms to police brutality. Can you explain the connection?

Chris Emdin: When I see young people who are not allowed to express their culture or use their voice, or have to control their physical body in a certain way to make their teacher feel more comfortable, I see those acts as violence against students. Those are not physical acts of violence, but violence on their spirits, on their souls, on their personhood, and it robs them of joy.

Emotional violence is equivalent to the physical violence they suffer at the hands of a police officer. In schools, students’ enthusiasm, spirit, passion can be incarcerated. I’ve taught in prisons. I’ve spoken to inmates. I’ve seen the physical structure of these places and it reminds me so much of urban schools.

MJ: You’ve worked with teachers from a number of charter schools like Success Academy, KIPP, and Uncommon Schools that deliver high test scores and use strict discipline tactics, such as sending kids out of class—and eventually home—for a long list of disciplinary infractions like untucked shirts or calling out the right answers without permission. What is your opinion of that approach?

CE: I get in trouble all the time for my critique of charter schools. I’m not anti-charter. I’m anti-oppressive teaching practices. I’m for young people. When I watch that infamous video from Success Academy where a teacher tears up the homework of one student [in Brooklyn], I’m less worried about the teacher yelling; the most troubling aspect of that video to me is that fear in the eyes of all the other children when that child was being yelled at. It’s no different to me when a police officer dragged that young woman [in Spring Valley High, South Carolina] out of a chair. Both of those groups of kids—in high school and elementary school—had the same kind of emotional responses on their faces.

“No excuses” all the time means no space to be a child: making mistakes, laughing out of turn, joking. You are robbing children of the opportunity to be children. This robbery of black and brown joy in our society is deeply problematic. When Cam Newton [quarterback for the Carolina Panthers] is called a “thug” after he dances to celebrate a touchdown, that’s a societal robbery of an expression of black joy. When a young person can’t celebrate something in the classroom in their own way after they got the answer right, we are seeing the same practice.

MJ: Secretary of Education John King Jr. is a big supporter of “no excuses” teaching approaches and a co-founder of Roxbury Prep, a charter school that has some of the highest test scores in the state, but that also suspended more students than any other charter in Massachusetts in 2014. Journalist Elizabeth Green summarized his position on the use of strict discipline—and the arguments of other supporters—stating, “[D]efenders argue that, subtracting freedom in the short term is actually the more radical path to defeating poverty and racism in the long term.”

CE: I think such arguments are ridiculous, if you consider yourself an educator. It’s so damaging. When you cite high test scores, what about broken spirits, souls, and kids who are pushed out of these schools because they have a different way of knowing or being? No one is talking about the low retention rate of these kids in college. No one is talking about kids who can’t go to these schools because they don’t test well. No one is talking about kids who are viewed as less intelligent because they don’t score well. People who changed the world—Albert Einstein, Charles Darwin—were often not successful in traditional schools. If we start focusing everything on a few metrics, we are squeezing the imagination out of young people.

Today knowledge is expressed through digital tools, your ability to write, your ability to be creative and artistic, and your ability to perform or be an effective orator or presenter, but our assessments of brilliance only come in a few stifling metrics. The whole system of assessments has to change.

MJ: How many of the teachers you coach are implementing the new practices you are you promoting?

CE: I don’t want to brag, but we’ve got teachers who are changing the world. Brian Moony is one of my students. He was able to do an amazing lesson plan on [Toni Morrison’s] The Bluest Eye and bring Kendrick Lamar to his school in New Jersey. He is a white dude who comes from a community that is very different, but he was able to change himself for his kids.

Is there resistance? Absolutely. “You are telling me to go into a barber shop in a community that I don’t know? What if something happens to me? What if I get robbed?” I usually say, “If you are afraid of getting robbed in the community where your students are from, you probably shouldn’t be teaching those kids.”

But it’s a small minority of teachers who resist. The majority of teachers want to be good. They come with a savior narrative but it comes from a place of wanting to do what’s right. When you show them evidence of good teaching, they want to do it.

MJ: You write that this book is for all teachers, not just white educators. Are you saying that black teachers can sometimes be prejudiced toward black students too?

CE: Absolutely. It may be harder for white folks who don’t have racial, ethnic, cultural similarities to learn how to build relationships with black students and incorporate diverse forms of intellectual expression into classrooms, but the strategies I describe in my book are also for folks of color who hold those biases—like the one I held when I started out teaching. By virtue of going through our teaching and learning system, you inherit these biases and you have to get rid of them.