“Everything,” Tom Wesley answers when I ask what’s ailing him. Diabetes. Multiple heart attacks. Chronic liver failure. “They’ve told me I’m dying.”

Wesley, a towering man in a salmon-colored corduroy shirt buttoned just at the top, is only 54. But for most of his adult life, he lived on the streets. He refused to stay in shelters because he didn’t like the structure; he says he also spent a significant time behind bars for heroin possession. “You could say I was using heroin,” Wesley says with a smirk. “But I don’t know who was using who—it sure used me up.”

He quit a few years ago—after losing two wives to overdoses. Around that time Wesley’s health problems started getting worse. Last year, a terrible pain in his abdomen brought him to San Francisco General Hospital, where he says he was admitted, via the emergency room, seven times in a matter of three months. At that point he was already used to the ER, having relied on it instead of primary care. “I wasn’t one for doctors,” he says.

Wesley’s experience isn’t unique. Sixty-six percent of the country’s chronically homeless people—those who have a disabling condition and who’ve been homeless for a year or more (or four times in three years)—are living on the streets. Chronically homeless adults have high rates of mental illness, substance use, and incarceration. They tend to be sicker than both housed people and other homeless people. And they’re less likely to use primary or specialty care to address their medical needs. Many make up the group of “super-utilizers“: patients who rack up huge medical costs from recurring yet preventable ER and hospital visits.

According to one estimate from the National Health Care for the Homeless Council, more than 80 percent of all homeless people have at least one chronic health condition. More than half have a mental illness. They are frequently the victims of violent crimes, and they’re more susceptible to traumatic injuries like assault and robbery. Their living conditions also make them more likely to have skin conditions and respiratory infections.

Perhaps it’s no wonder, then, that people experiencing homelessness have a life expectancy of between 42 and 52 years, compared with 78 for the general population. A recent study by Margot Kushel, a professor of medicine at the University of California-San Francisco, found that homeless people in their 50s develop geriatric conditions such as incontinence, failing eyesight, and cognitive impairment that are typical of people 20 years older. “When you see a homeless person in their 50s,” Kushel says, “you should imagine a 75-year-old.”

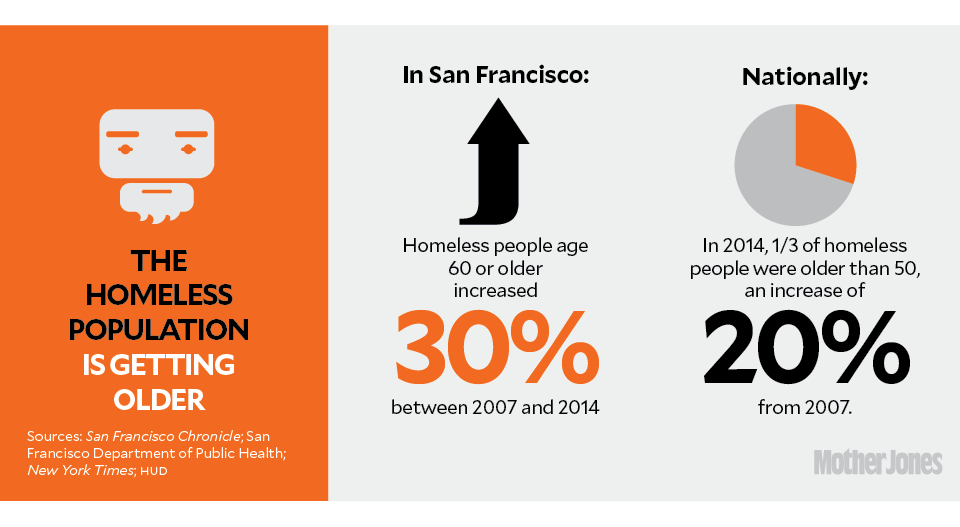

Kushel is also one of the founders of the San Francisco Medical Respite Program, a long-term medical shelter located on the edge of the city’s Tenderloin neighborhood that gives homeless people like Tom Wesley a place to recuperate after being in the hospital. With the homeless population in San Francisco and the rest of the country getting older—the number of homeless people age 60 or older in San Francisco increased 30 percent from 2007 to the 2014-15 fiscal year, and an estimated 31 percent of homeless people in the United States were older than 50 in 2014, a 20 percent increase from 2007—Respite and programs like it are seeing more people who are managing both chronic diseases and short-term illnesses. “We now have a group of homeless people that have more complex and co-occurring medical needs than ever before,” Kushel says.

For those homeless people who live on the streets or in a shelter—most of which are only open overnight—getting discharged from the hospital often means losing their meds, struggling to clean their wounds, or failing to make the specialist appointment across town. Others will get even sicker. Some will go back to the emergency room and start the process all over again.

“If you’re experiencing homelessness,” says Michelle Schneidermann, the medical director at Respite, “you’re thinking about where you’re going to get your next meal and how you’re going to keep yourself safe, not where you’re going to refrigerate your meds or make your next appointment.”

As a result, homeless people visit the hospital at rates up to 12 times higher than low-income people with housing. A 2007 study in Boston found that the majority of high emergency room users were homeless, according to the NHCHC. At one hospital, 16 homeless patients visited the ER a combined 400 times in one year. Hospital readmissions for homeless people are “strikingly high“; one study found that more than half of the homeless people it followed after discharge were readmitted to inpatient care within 30 days. Another recently published study found that homeless people had a 30-day readmission rate of 22 percent, compared with a rate of just 7 percent for housed people with the same health concern. And once in the hospital, homeless patients stay nearly twice as long as housed people.

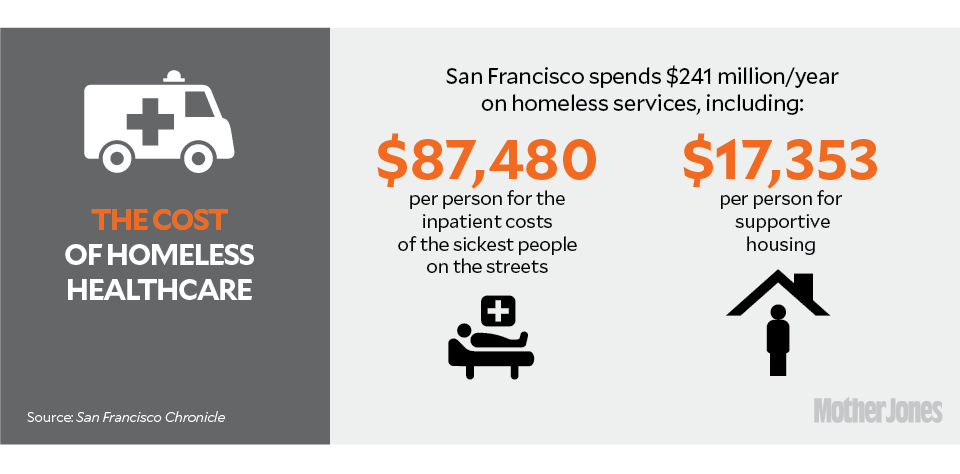

This reliance on emergency medical services is extremely costly to San Francisco, which spends more on health care than on any other type of homeless service. According to the San Francisco Chronicle, the city spends $241 million annually on homeless services, including an average of $87,480 in medical costs per year for each of the sickest people on the streets, compared with $17,353 a year for each person in supportive housing. Another estimate, from 2004, places the cost of hospital care for the city’s homeless people at more than $2,000 per person per day, by far the priciest service. “People who are homeless use the most expensive parts of the health care system,” says Schneidermann, who notes that SF General discharges an average of 130 homeless people each month.

This is despite the fact that, in a city like San Francisco, health insurance and access to outpatient primary care clinics are relatively accessible, thanks mostly to Medicaid expansion. “Access to insurance is not the biggest problem” Kushel says. “Their chaos of life prevents even those with insurance from getting care.” Indeed, evidence shows that even with access to primary care and specialty doctors, homeless people still use emergency services at rates higher than everyone else. In one study based out of Canada, where health coverage is universal, people experiencing homelessness still had longer inpatient stays and cost the hospital more than housed patients.

“Appointment-based care is difficult for all of us, let alone someone who is homeless,” Schneidermann says. “That’s where medical respite comes in.”

The first medical respite programs for the homeless were founded in Boston and Washington, DC, in 1985, but the model gained currency in 2006, when an elderly woman in a hospital gown and slippers was spotted wandering on Los Angeles’ Skid Row. The woman, a homeless 63-year-old with dementia, had been released from a nearby Kaiser hospital, which was later sued by the city and forced to establish new discharge rules. At least four other hospitals were caught “patient dumping,” including once incident when a paraplegic man was dropped on Skid Row and was later seen dragging himself, along with a torn colostomy bag, down the street.

There are now nearly 80 homeless medical respite programs, more than twice as many as in 2006. San Francisco’s Respite was founded in 2007 by the city’s Department of Public Health to address the acute medical needs (think broken bone or stab wound) of homeless patients who’ve ended up in General’s inpatient care via the emergency room. But beyond that, it might just offer an emergency room alternative to reach the city’s sickest, most vulnerable homeless population.

With only 45 beds and a waitlist at least equal that, Respite prioritizes people who are both the sickest and also the highest users of the ER. More than a quarter of Respite clients have seven or more chronic illnesses, and the average stay is five weeks, a figure that has risen as the client population has aged. (The longest stay was almost eight months.)

A 2006 study that compared homeless people who’d gotten into respite programs with those who hadn’t found that the respite group had fewer ER visits the following year. Among those admitted to the hospital following an emergency visit, the respite group stayed an average of three days, compared with eight days for the nonrespite group. A 2009 study found that discharging homeless people from the hospital to respite was associated with a 50 percent reduction in their likelihood of readmission in the next three months.

Still, despite evidence that medical respite programs reach the health system’s super-utilizers, only 10 respite centers nationwide are covered through Medicaid or Medicare. Instead, most programs rely on funding from hospitals, donations, or state and local governments.

And so Respite has its limitations. A quarter of its clients go straight from the program into permanent housing or long-term residential treatment. Another 50 percent are discharged back to a shelter with a case manager. The last quarter return to the streets.

The first time Tom Wesley was admitted to Respite, he was discharged to a single-room-occupancy hotel. He promptly ditched that setup, traveled to Cincinnati to see his children, and then returned to San Francisco’s streets. Shortly afterward, he was back in the hospital and then Respite, where he was diagnosed with chronic liver failure and moved into what he calls a glorified nursing home—a permanent supportive housing apartment just blocks away. Feeling like he’d tied up loose ends, he decided to stay.

When I meet Wesley in Respite’s foyer, in front of the room that houses the few dozen beds where the men stay, he’s been out for a few months already. He’s wearing a Golden State Warriors cap, and his eyes are blood red. We take the elevator up and walk to the facility’s small meeting space, past the dining room where patients receive three meals a day and the single-person rooms where women stay.

He grabs a seat with his back facing the bright light coming through a window. As he tells me about his connection to Respite, Wesley’s legs bounce up and down. “If there were more programs like this,” he says, “people wouldn’t be dying on the streets every day.”