James West

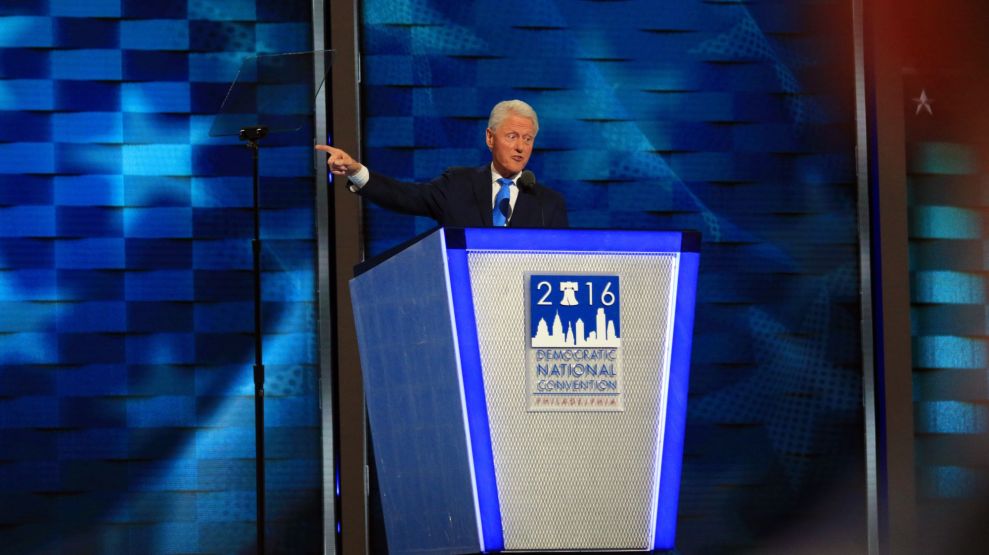

When Bill Clinton spoke to the Democratic convention on Tuesday night, he warmly recalled the time in 1985 when Hillary Clinton learned about a preschool program in Israel that taught low-income mothers how to become the first teachers for their children and then introduced it in Arkansas. When Joe Biden was at the podium, he declared, “Hillary understood that for years, millions of people went to bed staring at the ceiling thinking, ‘Oh my God, what if I get breast cancer or he has a heart attack? I will lose everything. What will we do then?'”

Tim Kaine on Wednesday night pointed out that Clinton had fought “to get health insurance for 8 million low-income children when she was first lady.” He added, “When you want to know something about the character of somebody in public life, look to see if they have a passion that began long before they were in office, and that they have consistently held it throughout their career.” And President Barack Obama, in a rip-roaring stem-winder, asserted, “Hillary’s still got the tenacity that she had as a young woman working at the Children’s Defense Fund, going door to door to ultimately make sure kids with disabilities could get a quality education.”

With Hillary Clinton’s disapproval ratings nearly as high as Donald Trump’s record-setting numbers, the message of the Democratic gathering in Philadelphia this week has been simple: She is better than you think, whether you’re a Republican predisposed to dislike a Democrat but now concerned about Donald Trump or a Bernie Sanders supporter who views Hillary Clinton as the flag carrier for a corrupt corporatist elite. Bill Clinton even acknowledged that his wife, thanks to her detractors, has become a “cartoon” for many. He added, “Cartoons are two-dimensional. They’re easy to absorb. Life in the world is complicated.”

And so is Hillary Clinton. She is a onetime former McGovern Democrat who voted to let George W. Bush launch the Iraq War. She did help create a health insurance program for millions of low-income children in the 1990s but also supported welfare reform that progressive social policy experts decried. She has denounced big-money politics and called for overturning Citizens United but pocketed personal and campaign funds from Goldman Sachs and other Wall Street interests. She has resolutely stood up to false charges from her say-anything foes regarding the tragic Benghazi attack, but she did screw up with the emails. She can be highly competent and also possess tremendous blind spots. She knows policy and campaigns awkwardly. The Clinton White House years were marked by her unsuccessful but well-intentioned effort to achieve national health insurance, her husband’s fight to beat back draconian GOP cuts in Medicare, Medicaid, environmental and education funding, and assorted controversies, some real (her cattle futures trading, last-minute pardons, the Lewinsky affair) and some trumped up (Travelgate, Filegate, Vince Foster’s death). She has long supported progressive causes (abortion rights, affordable child care, LGBT rights, family leave, immigration reform, women’s rights, gun safety, climate change) but was a partner in her husband’s ideological triangulation and, more recently, has been less than steady in opposing the proposed TPP trade deal. It’s no wonder that one leitmotif of the Dems’ week in Philadelphia was the difficulty many Sanders delegates have coming to terms with Clinton as the Democratic nominee.

As the the convention managers and leaders of the Clinton campaign pushed a message of party unity in celebration of the first woman to win a major party’s nomination—and Sen. Bernie Sanders joined in by declaring in his prime-time speech that it was essential to support Clinton and that she would make an “outstanding” president—a large chunk of Sanders delegates noted they were not ready for her. Though the Sanders campaign had achieved so much more than past within-the-party insurgencies (Jesse Jackson in 1984 and 1988, Jerry Brown in 1992) by winning significant victories during the party platform and rules deliberations, many Sanders delegates during the week focused on grievances and slights: the leaked Democratic National Committee emails that showed (no shocker) that some Democratic staffers were not Sanders fans; the Clinton campaign’s embrace of Debbie Wasserman Schultz after she resigned as party chairman; the convention managers preventing a prominent Sanders supporter from speaking from the stage. Rather than celebrate their triumphs, many Sanders delegates groused repeatedly that the Clinton campaign had not reached out to them. They openly rejected Sanders’ instruction to refrain from protests during the convention proceedings and to embrace Clinton in the crusade against Trump.

Throughout the week, numerous Sanders delegates said, “I’m not there yet.” They insisted it was still up to Clinton, whom some dismissed as a “neoliberal hawk” and phony progressive, to win them over and to convince them she would stick to her opposition to the TPP (the policy issue that most engaged Sanders delegates). They voiced disappointment that Clinton had not adopted the Sanders position on fracking, single-payer Medicare for all, and Middle East policy.

Norman Solomon, a Sanders delegate and coordinator of the Bernie Delegates Network (which is not affiliated with the Sanders campaign), complained that the convention was full of “cheerleading for war.” Chuck Pennacchio, a Sanders delegate from Pennsylvania, warned that Sanders delegates were not content to “hand the ball” to Clinton. He added, “Clinton and her surrogates need to get out in the field and say [to Sanders supporters], ‘I really want to hear you.’ And that has not happened.” He griped, “When I talk to the Hillary people, they say, ‘Get over yourself.'”

Older Sanders delegates routinely noted that the millennials who had boarded the Bernie Express as volunteers and delegates needed more time to process their defeat and that they had to be courted by Clinton. A senior Sanders strategist insisted that Clinton had to accept the responsibility of engaging with this group via texts, tweets, and videos. “There is a lot of mistrust among our young Bernie voters about how the process was conducted,” said Donna Smith, the executive director of Progressive Democrats of America and a Sanders advocate. “To think young people would make a pivot in four days is not very realistic…It is not a given that people will hold their nose and vote for her.” On the last night, many not-there-yet Sanders delegates attended the convention wearing yellow T-shirts emblazoned with the slogan “Enough is enough.”

It was unclear how many Sanders backers were in such a dark place. Ten percent? Half? More? It did seem that some of the independent senator’s supporters would never accept Clinton and that despite Sanders own statements many of his ardent followers had not absorbed the message that their insurgency had racked up impressive gains. After listening to several Sanders delegates say that Clinton was not addressing their concerns, Tony Russomanno, a Clinton delegate from California, wondered if the Sanders die-hards could ever be satisfied and deal with the reality that Clinton had won the nomination. Sanders “people are conflating being listened to to getting their own way,” he said with a sigh.

Whether or not energizing Sanders-ites is a top priority for the Clinton camp—and it’s open to debate whether it’s more important for her to excite the progressive base or to draw in moderates (or to do both) in order to bag the few swing states necessary for victory—she did reach out to independents and Republicans. Throughout the convention, speakers and videos made the case to moderate Rs and independents (see Michael Bloomberg’s speech) that in a world where Trump could end up in the White House and in command of nuclear weapons, Clinton is a just fine if not perfect alternative.

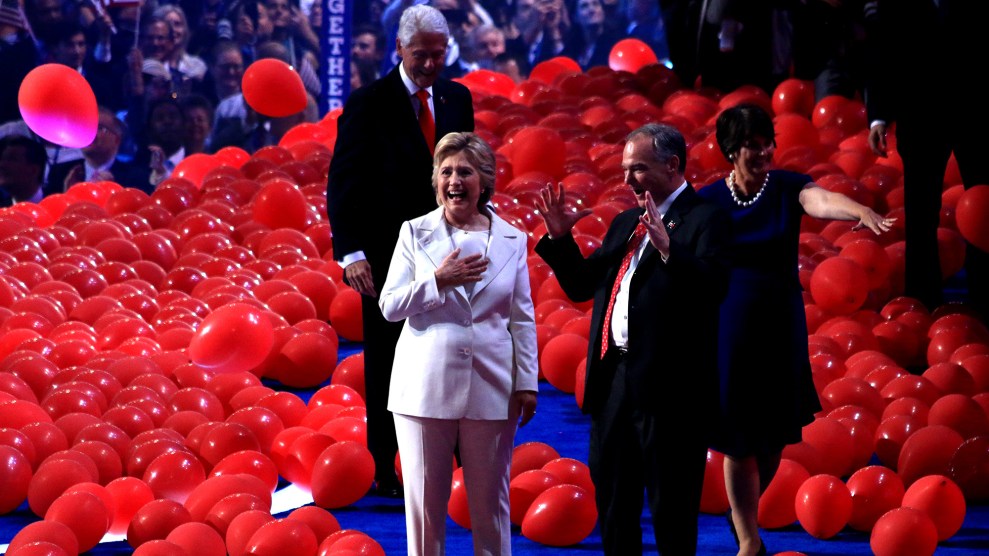

With her acceptance speech, Clinton sought to depict herself as an advocate of compromise, steady leadership, and across-the-aisle conversation. She came across as a workhorse. She noted, “I sweat the details of policies.” The level of lead in drinking water. The cost of prescription drugs. The number of mental health facilities in a state. She confessed she might not be the best politician: “The service part has always come easier to me than the public part…I get it: Some people don’t know what to make of me.” And she went the Full Bernie, declaring she was prepared to collaborate with the Sanders crowd to advance the “progressive” platform the two campaigns developed together. Addressing Sanders supporters, she declared, “I heard you. Your cause is our cause.” She touched all the Sanders issues: economic inequality, big-money corruption, Wall Street greed, climate change, unfair trade deals, expanding Social Security, tuition-free college, and more. It was an outright play for their support.

Clinton slyly slammed Trump, casting him as the candidate of fear, division, and insult. She poked at his habit of stiffing small-business contractors. “Donald Trump says he wants to make America great again,” she jabbed. “He could start by actually making things in America.” She zeroed in on his temperament: “Imagine him in the Oval Office, facing a real crisis…A man you can bait with a tweet is not a man you can trust with nuclear weapons.”

Her overall theme was “stronger together.” And she is trying to build a non-Trump coalition that stretches from Sanders progressives to Reaganesque Republicans who fear Trump. She juxtaposed her desire for communal politics with Trump’s politics of the ego. It was an effective speech, and Clinton succeeded in illustrating the stark choice this presidential election presents.

Within the convention hall, there were plenty of Democrats excited to be led by Clinton, inspired by her work and stances over the years, and thrilled by the historic nature of the moment. But for many Democrats, progressives, independents, and GOPers horrified at the prospect of a bullying, bigoted, and erratic celebrity tycoon becoming president—and perhaps not fully enthused by Clinton—Clinton has to sell herself as the best option available. Hours before her speech, Robby Mook, the Clinton campaign manager, acknowledged that some voters are “skeptical” of Clinton and noted that she must show them her “core values and core motivations and her lifetime of work.” In a way, her task in the next three months is to show those skeptical voters, in the words of Stuart Smalley, the Al Franken SNL character, “I’m good enough, I’m smart enough, and doggone it, people like me.” And if some voters feel they are settling by voting for her, so be it. Clinton has spent decades in public life, and there won’t be a new Hillary in the weeks ahead. She is unlikely to become an inspirational candidate. She is unlikely to lower dramatically her approval ratings. She won’t become a progressive hero. She won’t become trusted by Republicans who have long eyed the Clintons with suspicion. She is, though, the only chance to stop Trump’s takeover of America—and her job is to persuade voters that for now she is indeed the last best hope.