AP Photo/The Star Tribune, Glen Stubbe

In 2011, at the ripe old age of 28, GOP political consultant Nick Ayers was ready to hang up his spurs and retire to a genteel life outside politics, but God brought him back. God wanted Ayers to use his significant talents to help restore America’s prosperity and liberty. Ayers announced all of this in a blast email he sent that year to friends, informing them that he would forgo private-sector riches and use his talents to take Minnesota Gov. Tim Pawlenty to the White House.

It rubbed people the wrong way. And then it became a punch line when Pawlenty’s campaign, which Ayers managed, crashed and burned in a blur of wasted money, long before the 2012 Republican primary ever really got going.

Now Ayers is back on the national stage.

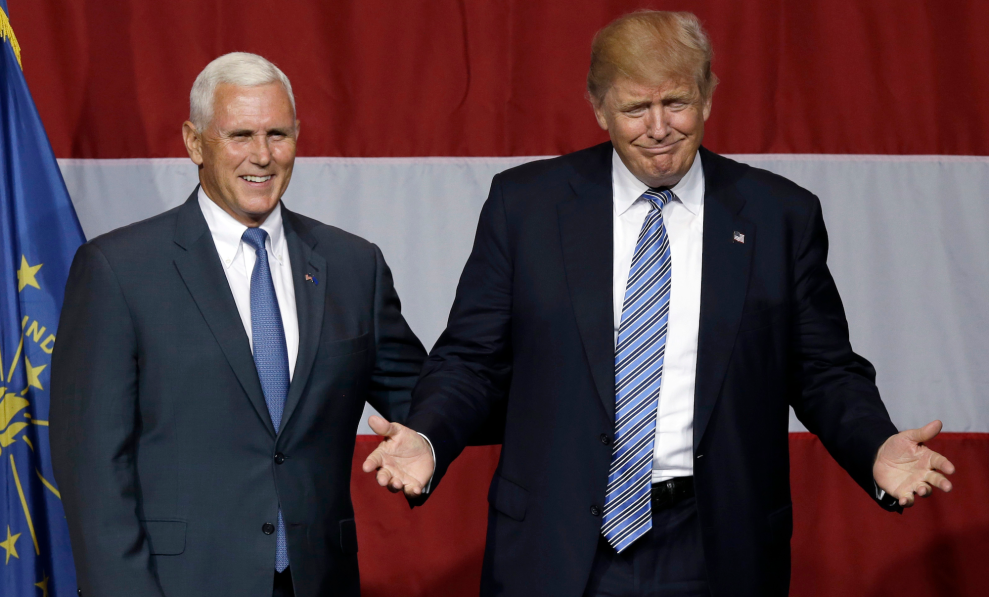

Ayers started working this year as a top political adviser to Indiana Gov. Mike Pence, whom Donald Trump announced last week as his vice presidential pick. With his boss’ elevation, Ayers is, according to media reports, suddenly a core member of the Trump presidential campaign. In many ways, Ayers is the perfect man to assume a significant role in Trump’s world. He is a genuinely successful political operative, apart from the Pawlenty train wreck. In 2010, he led the Republican Governors Association to a string of victories. And in 2014, he helped two wealthy Republican businessmen with no political experience win tough races to become governor of Illinois and a US senator from Georgia—and he appears to have been the link between their campaigns and conservative dark-money groups that savaged their opponents.

There’s also something Trumpian about the way Ayers comports himself. In the email announcing his decision to accept the responsibility of running Pawlenty’s campaign, Ayers words were every bit as self-aggrandizing as Trump’s typical rhetoric:

As He often does in walks of faith, He has called me to a higher purpose. I believe that our Nation is truly on the wrong path. We need a new direction that is positive and hopeful. Simply said, we need new leadership. I believe that Governor Pawlenty is best positioned to provide that leadership. Therefore, I am pleased today to join Governor and Mrs. Pawlenty in their pursuit of the presidency.

The email was just the start of Ayers’ image problems. Shortly after he took the job with the Pawlenty campaign, Minneapolis alt-weekly City Pages discovered a dashboard camera video of Ayers being arrested in 2006 for driving while intoxicated. At the time, Ayers was the campaign manager for the governor of Georgia, Sonny Perdue, a fact that Ayers immediately mentioned to the arresting officer. (The charge was eventually reduced to reckless driving.)

The video and a second one recording Ayers’ ride to the police station in handcuffs, during which he attempted to explain to the arresting officer his role in politics, were plastered around the internet with nothing short of glee, under such headlines as “Pawlenty’s egotistical campaign manager’s DWI arrest video hits YouTube.”

The fallout from the Pawlenty campaign failure, on the heels of such a grand proclamation of his role in it, did not do Ayers’ reputation any favors. Even before the floundering campaign’s finish, the sniping and snarling among GOP operatives had gotten so loud that the conservative Daily Caller proclaimed Ayers “the most hated campaign operative in America.” The Daily Caller piece, which concluded that Ayers’ great success at a young age led to hubris, featured several sources offering their unfriendly opinions of Ayers:

Still, 2010 made Ayers look like a rock star, and it was during this time in that Ayers’ contemporaries began to notice a change in him. “He’s a very ambitious kid. He’s a smart guy. He’s not evil. But his ego grew along the lines of the federal deficit,” said one strategist who worked with Ayers in the past. “It’s all about him,” said another operative. “He’s David Hasselhoff.”

When the campaign was faltering, rumors spread that Ayers was going to bail on Pawlenty and work for Texas Gov. Rick Perry. CityPages opined, “Everybody Hates Nick Ayers.”

In 2014, Ayers reinvented himself, this time with a much lower profile, finding new success on the shadowy edges of the dark-money world, where avoiding scrutiny is the point. After the Pawlenty debacle, Ayers went to work for Target Enterprises, an ad-buying firm based in Los Angeles. Ayers and his new employer picked up work consulting on the campaign of Bruce Rauner, an extremely wealthy Republican businessman from Chicago, who ran for governor as an outsider against a crowded field of Republicans and a troubled incumbent Democrat. Shortly before Ayers went to work for Rauner, his opponents came under fire from mysterious outside groups.

The groups, based in Ohio, emerged out of the blue to lob factually dubious attacks at Rauner’s opponents, and then disappeared. Far more experienced Republican candidates and would-be candidates fell by the wayside. The Ohio groups doing the attacks—with vague names such as Jobs & Progress Fund—hid the source of their money and the motivations for the attacks. (It later came out that one of the groups was partially funded by Ayers’ old employer, the Republican Governors Association.) But the limited paper trail they left showed that they had hired Ayers’ consulting firm. Rauner’s campaign denied any knowledge of the outside groups or who was funding them, despite their close ties to Ayers.

At the same time, another wealthy political novice was launching his own bid for the open US Senate seat in Ayers’ home state of Georgia. David Perdue, the former CEO of Dollar General, had no political experience, but he did have two well-connected cousins. One is Sonny Perdue; the other, a more distant cousin, is married to Ayers. David Perdue cruised to victory after fighting off a more experienced Republican primary opponent and then-Democrat Michelle Nunn, the daughter of former Sen. Sam Nunn of Georgia. Along the way, Perdue hired Ayers’ firm, and just like Rauner, he benefited from a well-timed, factually dubious barrage of attack ads aimed at his primary opponent and paid for by the same network of Ohio dark-money groups that backed Rauner.

It’s against federal election law for a candidate to coordinate with an outside dark-money group, but Ayers brushed aside questions on whether he had been involved with the organization of the dark-money attacks against Perdue’s opponents while his company worked for Perdue. Ayers told a reporter that there was “a firewall” within the company, which made sure there was nothing improper occurring between the candidate and the outside groups he worked for.

While Trump matches the profile of an Ayers candidate—a wealthy GOP businessman who’s running on his personal wealth as evidence of a business acumen that can shake up politics—Pence does not. Perdue and especially Rauner cultivated images of relative moderation, but Pence is known as a strong social conservative. While the Republican Governors Association has long been one of the most significant backers of Pence, Ayers only recently began working for him.

According to campaign finance records in Indiana, Ayers was paid $33,000 on April 14 and received a second check for the same amount on May 3—the day of the Indiana primary, and the day that Ted Cruz suspended his campaign and Trump became the presumptive nominee. He was paid another $27,000 in early June. The roughly $30,000 a month that Pence is paying Ayers is significantly more than he pays any other campaign staffers. Considering the timing, it’s possible that Pence may have brought Ayers on for the purpose of getting picked as the vice presidential candidate, back when he was still protesting he was not interested in the job.