Read Mother Jones reporter Shane Bauer’s firsthand account of his four months spent working as a guard at a corporate-run prison in Louisiana.

I met Damien Coestly on my first day on the job as a guard at Winn Correctional Center, a private Louisiana prison then run by the Corrections Corporation of America (CCA). I’d been sent to monitor the suicide watch cells in the segregation unit. I pulled my chair across from Coestly’s cell as he sat on the toilet, his body hidden under his tear-proof suicide smock. He told me to “get the fuck out of here” and threatened that if I didn’t he would “get up on top of this bed and jump straight onto my motherfucking neck.”

When I was at Winn, inmates on suicide watch were kept in solitary confinement. They weren’t allowed to keep much more than a small amount of toilet paper, their suicide smocks, and suicide blankets. They had to sleep on a steel bunk, often without a mattress. They also received worse food than the rest of the prison population: A typical meal consisted of one “mystery meat” sandwich, one peanut butter sandwich, six carrot sticks, six celery sticks, and six apple slices. There were no mental health professionals stationed in the unit—it was just me and another guard watching over four inmates in their cells.

“This dumb-ass motherfucking CCA. This tops the charts in nonrehabilitation,” Coestly told me, leaning against the bars of his cell. “This Winnfield, man. Till you shut this mothafucker down, it ain’t go’ change.” He tried to hand me a Styrofoam cup through the food slot, asking if I would sneak in some coffee for him. At dinnertime, he demanded a vegetarian bag from the Special Operations Response Team (SORT), the SWAT-like tactical squad that was patrolling the unit. He didn’t get one, so he picked the meat out of his sandwich and ate the bread and carrot sticks. Afterward, I watched him sleep, wrapped in his suicide smock like a cocoon.

After I quit my job at Winn in March 2015, a lawyer in Louisiana told me that a woman named Wendy Porter had read about me working at the prison and wanted to talk to me. Her son was Damien Coestly. Porter told me Damien had committed suicide six months after I’d seen him. He had just turned 33.

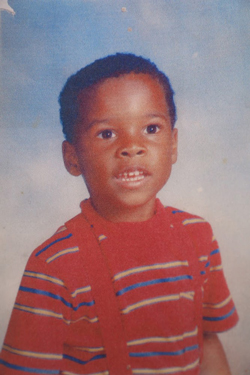

Johnny Coestly remembers the last time he saw his younger brother Damien. They were in a hotel room in a New Orleans suburb, laughing and joking as a hurricane raged outside. Damien, then 20 years old, was on the run. A few months earlier, three men had confronted him in a club. One was angry because Damien had been “messing” with his girlfriend. The man spit in his face. Damien shot all three, killing one.

Not long afterward, Damien was arrested and sentenced to 30 years. He ended up in Winn. As an ex-felon, Johnny says he was never allowed to visit. He and Damien frequently talked on the phone, but the calls ended when Johnny got locked up for selling drugs. Then, on June 12, 2015, one year into his sentence, Johnny was suddenly told to pack his stuff and was put on a bus to Winn. He thought he was going to see his little brother for the first time in 13 years.

Johnny hadn’t yet finished the intake process at Winn when a guard took him into a room where the warden and the prison’s mental health director were waiting. They had bad news: Damien had attempted to kill himself in the segregation unit that afternoon, and had been sent to the hospital, unconscious. “It’s like my world had stop,” Johnny wrote to me using the prison’s email system. Before the information could sink in, Johnny was put back on a bus and shipped to another prison across the state.

At first, Johnny refused to believe that Damien would try to take his own life. His brother had never said anything to him about depression or suicide. At Winn, however, Damien’s fragile mental state was no secret. Prison records obtained from the Louisiana Department of Corrections by Anna Lellelid, the lawyer who currently represents his family, show that he went on suicide watch at least 17 times in the three and a half years before he died. One inmate wrote to me that Damien had told him, “He was not going to do all his time. [W]hen the time came and he was at peace with God, he was going to kill himself.” This inmate also said Damien had expressed regret for killing the man who’d spit on him. “He said that he rather be in the same place that that guy was [than] do his time in prison.”

In records obtained by Lellelid, Winn’s part-time psychologist noted, “Inmate stated that he was feeling depressed and worried that he was going to kill himself, because he was hearing the voice of the person that he killed and that he was telling him to kill himself and join him.” On another occasion, a prison counselor wrote, “He says [he’s] done with CCA and his life.” CCA responded to one question about Damien Coestly’s death for this article; it has yet to respond to more than 20 additional questions sent more than a month ago.

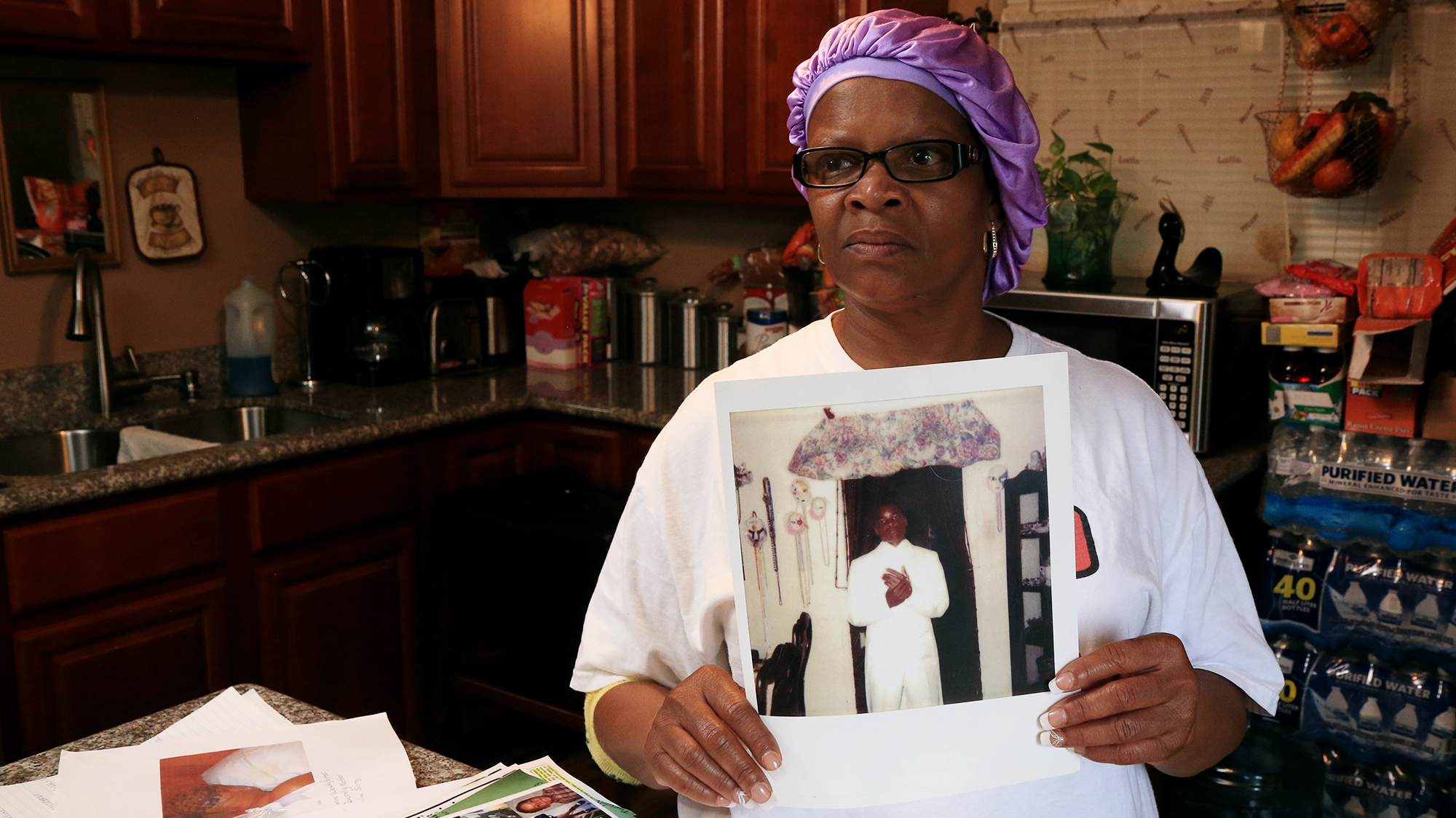

Earlier this year, I visited Wendy Porter at her home outside New Orleans. She was wearing a T-shirt that read, “God is Good!” and a floppy purple cap to cover the scars from her recent brain surgery. When I’d initially contacted her, one of her most pressing concerns was how to pay the bill the hospital had sent her for Damien’s medical records. It was clear that she’d had a hard life. Her two remaining sons were in prison. Their fathers and Damien’s were either behind bars or dead.

She was navigating her loss while reckoning with the fact that she’d missed a lot of her boys’ childhood because she’d been smoking crack. “When I would put the crack in a pipe, I would be looking in a mirror asking God to please help me,” she said as we talked in her living room. When Damien got locked up, she was serving a short prison term. Yet she was eager for me to know that she never stopped loving her kids. She quit using drugs and got back into their lives. Even when they were in prison, she would always send them what little she could scrape together.

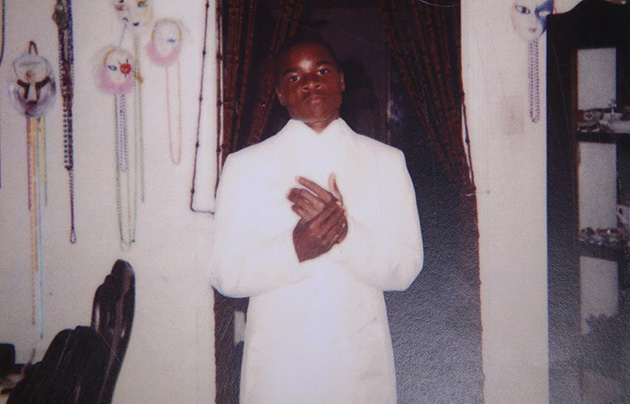

After Damien died, the prison turned his belongings over to Porter. Everything he owned fit into a single box. When she eventually opened it, she found sugar packets and years of letters she had written him. There was a photo of him sitting in a prison yard in front of a row of books—biographies of Malcolm X and Che Guevara and titles on astronomy, astrology, and health. There was a grievance form in which Coestly claimed he’d mailed the gold caps from his teeth to his mom, but they went missing. (CCA turned down his complaint.) There was another in which he complained that the rehabilitative efforts at Winn were inadequate and that he’d been on a wait list for 12-step and mental health programs for two years. (It is not clear if CCA received or reviewed this complaint.) “Just because I have 20 years left in prison doesn’t mean that I’m nonexistent and that I don’t matter,” he wrote.

Mixed in with Coestly’s paperwork was a printout from CCA’s website on which he highlighted the phrase, “We constantly monitor the offender population for signs of declining mental health and suicide risk, working actively to assist a troubled offender in his or her time of need.” Yet mental health staffing at Winn was thin while I was there. It consisted of one part-time psychiatrist, one part-time psychologist, and one full-time social worker for more than 1,500 inmates. (CCA confirmed this, adding that “the staffing pattern for mental health professionals at Winn was approved by the Louisiana Department of Corrections.” However, DOC documents show that it had asked CCA to hire more mental health employees at Winn.) The prison’s single social worker told me that most Louisiana prisons had at least three full-time social workers. Her caseload, she said, included 450 inmates with mental health issues.

In a 2014 grievance, Coestly claimed that while on suicide watch in Winn’s Cypress unit he was jolted awake by two guards who dragged him out of his bunk, cuffed him, made him stand naked in the hallway, and slammed him against the wall repeatedly. In another complaint, he wrote that he and other inmates were left on suicide watch with no guards to monitor them. He claimed that two inmates then came into the tier and threw milk cartons full of feces on the inmates in the suicide watch cells while the guards stood by, doing nothing to stop them. “Check the cameras ASAP because this incident is going to ruin Winnfield’s reputation with this criminal act,” he wrote. “I fear for my life back here in Cypress because there’s nothing but chaos back here.” (It is not clear if CCA received or reviewed these complaints.)

Among the records turned over to Porter was a sheaf of legal documents. Coestly had been studying law in prison. After bringing a case against Winn in state court over two pairs of shoes taken by guards, the Department of Corrections asked CCA to reimburse him $47.32. Was he preparing a more substantial case against the prison? According to Lellelid, Coestly had collected documents from lawsuits brought on behalf of inmates who had committed suicide in custody. He had filed at least one grievance claiming that guards were putting him on suicide watch, naked, without consulting the mental health staff. (DOC policy stated that mental health professionals should make suicide watch assignments whenever possible; in their absence, they were to be notified immediately to assess the inmate as soon as they could.) He had appealed to the Louisiana DOC to review his claim, a necessary step before an inmate can file a federal civil rights claim. The DOC denied his appeal.

Coestly didn’t just protest on paper. He frequently went on hunger strike. At times it was because the prison would not give him a vegetarian meal as he’d often requested. The prison didn’t offer vegetarian options, so he ate the regular meals without the meat. Other times, he stopped eating because he felt he was not receiving adequate mental health services. Once, the prison psychologist reported in Coestly’s medical records that Damien was on suicide watch and “upset because he felt that he was not getting the appropriate care from mental health.” He wrote that Coestly complained that claiming to be suicidal was the only way to get a meeting with the psychiatrist. “Inmate has a long history of playing games and trying to manipulate the system,” the psychologist wrote.

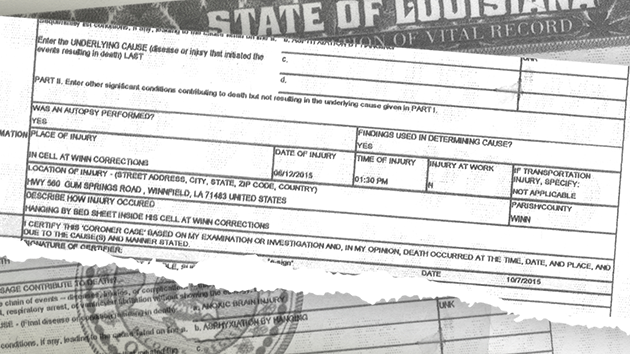

Winn’s assistant chief of security, whom I’ll call Miss Lawson, since she asked not to be named, was one of the CCA employees assigned to investigate Coestly’s death. She told me that he had been on suicide watch for “a couple weeks at least” when a SORT officer decided to take him off watch and put him in a regular segregation cell without, she noted, the approval of mental health staff. (State policy says “suicide watch may be discontinued or down-graded only by a mental health professional or physician.”) “Me and [the social worker] got on ’em bad about moving him,” Miss Lawson recalled.

Coestly was put in a cell with an elderly man who was severely mentally ill, Miss Lawson told me. Unlike inmates on suicide watch, prisoners in segregation, or seg, were not supposed to be under constant watch. Guards were supposed to check on them every 30 minutes. An inmate who had been a few doors down from Coestly in seg later told me that he saw Damien taken out of his cell to make a phone call. Afterward, the prisoner heard Coestly tell a SORT officer he was feeling suicidal. The officer said he would return to get Coestly, but never did. Coestly repeated several times that he was going to kill himself, the inmate recalled. Miss Lawson said that according to prison policy, that should have gotten him automatically placed on suicide watch.

On the afternoon of June 12, 2015, the man in the cell next to Coestly—I’ll call him Tony—pounded on the metal above his door. “Dude is hanging himself!” he shouted. SORT officers stormed down the tier with pepper spray in hand, shouting, “Who the fuck is beating?” (Tony likely had been in Cypress because of me. I’d caught him with synthetic marijuana and he wound up in seg.) Tony told me some details of that day through JPay, the prison’s monitored email system. He wrote that “CCA could of saved Damien’s life if only they would of listened to him when he told them he had some problems.” He asked me to pay him for the full story. When I declined, he refused to tell me more.

Miss Lawson told me Coestly had tied a sheet to the top of his cell’s bars, looped it around his neck, and jumped off the top bunk. When the SORT officers arrived, his cellmate, sedated by sleeping medication, was struggling to hold up Coestly so he could breathe. Coestly was still alive and taken to a hospital, where his mom saw him. “It was bad,” Porter recalled. “He had skin rolling off his ankles.” Coestly remained shackled even as he lay unresponsive, she said. “Why you got shackles on him? What you think—he going to break out and run?”

Coestly remained on life support for 19 days. Porter said her son had once been a “thick something” who liked to work out. But when he died, “He was so little.” An autopsy found that he weighed 71 pounds, nearly 50 pounds less than he had weighed six months earlier.

In their reports about the incident, Miss Lawson said, CCA’s SORT officers “covered up a lot of stuff they shouldn’t have.” She said video from the prison’s cameras showed that it had been an hour and a half since they had done a security check on Coestly’s tier. “If they had been going up and down the tiers like they were supposed to, then it wouldn’t have happened,” she believes. No Winn employees were ever disciplined as a result of the investigation, she said.

I asked CCA spokesman Steven Owen about Coestly’s death. “You have your facts wrong in this case,” he wrote back. “The warden at Winn requested compassionate release for Mr. Coestly from the Louisiana Department of Corrections, which was granted. The inmate was hospitalized when he passed away.” Beyond noting that Damien did not actually die at Winn, he provided no further details. Lellelid confirmed that the DOC had granted Damien a compassionate release, but only as he lay in the hospital and “because he was brain dead.”

Coestly’s mom and brother hope to pursue a lawsuit against CCA for negligence in Damien’s death. Yet it is unlikely that the question of who is responsible for Coestly’s death will ever be decided in court. Louisiana law only allows a year for family members to file a wrongful-death lawsuit. And despite her recent involvement in her sons’ lives, Porter gave up custody of Damien when he was about five years old. Legally, her aunt, who became Coestly’s guardian, could have brought a case against CCA over his death. But she has advanced Alzheimer’s and does not understand that Damien is dead.

“I would love to sue them for the anger they caused my son, the pain,” Porter told me. “He suffered. He weighed 71 pounds. That was like somebody starving.” Her voice cracked. “I keep food in my house. I give people food!” she shouted, weeping. She paused and took a deep breath. “It’s all about a dollar. That’s what you is, a dollar sign to them. You know what my son said? He said it over the phone. He said, ‘When I get through with them, they’re going to shut this place down. It ain’t fit for an animal.'”

Additional research by Madison Pauly