Rui Vieira/Zuma

The internet is the worst ballot box of all, according to three research and public-interest groups who are slamming states’ use of online voting and urging people to protect their privacy by physically mailing in their ballots instead.

“Internet voting creates a second-class system for some voters—one in which their votes may not be private and their ballots may be altered without their knowledge,” write the authors of The Secret Ballot at Risk: Recommendations for Protecting Democracy. Caitriona Fitzgerald of the Electronic Privacy Information Center, Pam Smith of the Verified Voting Foundation, and Susannah Goodman of the Voting Integrity Campaign of Common Cause, who were the authors of the report, point out that states either have constitutional provisions or state statues guaranteeing the right to secret ballots, but that “because of current technological limitations…it is impossible to maintain separation of voters’ identities from their votes when Internet voting is used.”

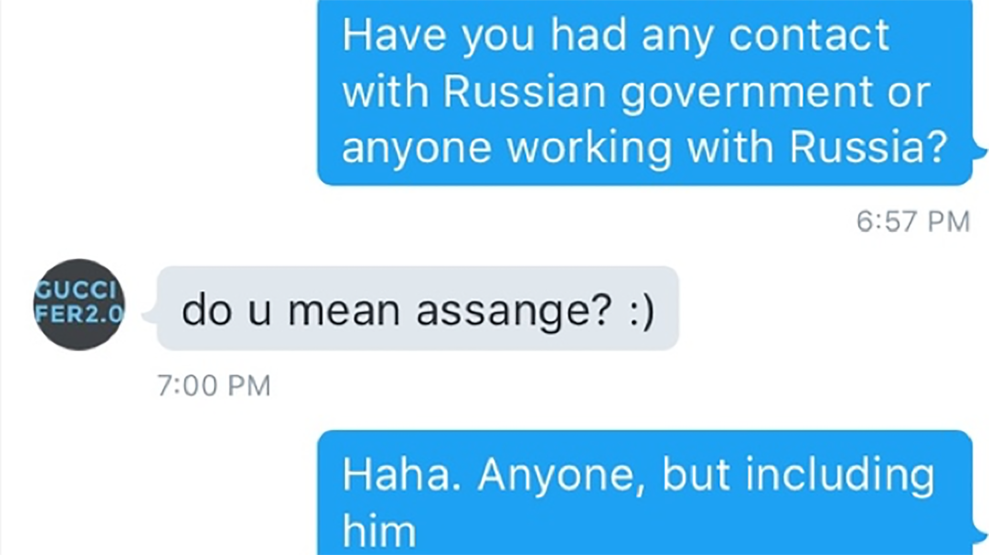

The report comes at a time when hacking—especially from foreign interests seeking to influence US elections—has become a major theme of the presidential race. This summer, data from the Democratic National Committee, other Democratic organizations, and perhaps more than 100 high-ranking Democrats were released by hackers the US government says were working with or on behalf of the Russian government. The authors of the report told reporters on a conference call Thursday that they’re glad these recent episodes have raised consciousness about information security, but that their report focuses on the less-discussed but critically important area of ballot secrecy.

“A lot of the vulnerabilities of online voting are discussed pretty frequently,” said Pam Smith of the Verified Voting Foundation. “The reason that we wanted to do this report is because the secrecy issue, the privacy issue, is something that doesn’t get as much attention.”

The researchers argue that maintaining ballot secrecy is key to preventing vote coercion, vote buying, and tampering. That’s why 44 states have a constitutional provision guaranteeing voting secrecy, while six states and Washington, DC, have statutes that provide for secret voting. In some states, like Delaware, for example, it is a crime for election officials to reveal a voter’s vote, according to the report.

In all, 32 states and the District of Columbia offer some form of voting over the internet (email, fax, or online portal), according to the researchers. Most of those states use the systems for their overseas military or absentee voters, but in Alaska, all absentee voters can submit their ballots online. In 28 of these states, voters using the online systems are required to waive their right to casting a secret ballot. But Idaho, Mississippi, North Dakota, and Washington do not give any warning about ballot secrecy. The researchers note that Montana has a statutory requirement that votes cast over the internet remain secret “despite the fact that this is technologically impossible.”

With current technology, ballots submitted online cannot be separated from the voters who cast them, which is why voters are required to sign away their right to privacy. Additionally, if the server hosting all the emailed ballots is compromised, the votes cast could easily become public, along with the voters’ identifying information associated with the ballot.

Online ballots can also easily be tampered with. Galois, a computer security research firm, simulated an attack in 2014 and demonstrated how the flaws associated with submitting ballots online could enable a single hacker to manipulate election outcomes. Their attack was developed over only a few days, according to the firm, and would be very difficult to prevent or detect.

Computerizing all votes is a nonstarter for many in the digital security world. In 2010, officials in Washington, DC, tested a system that would allow overseas absentee ballot voters to vote online, and they invited researchers or anybody else to try to compromise the system during a mock election. Within 48 hours, a team from the University of Michigan “gained near-complete control of the election server [and] successfully changed every vote and revealed almost every secret ballot,” the researchers noted in a 2012 paper describing the episode. The researchers added that DC election officials didn’t notice the breach for nearly two business days, “and might have remained unaware for far longer” had they not left a glaring clue: They modified the “Thank You” page that appeared at the end of the voting process so the University of Michigan fight song, “The Victors,” would automatically start playing.

The researchers don’t say election officials should avoid the internet altogether. Instead the internet can and should be used to facilitate voter registration, help voters find polling places, and help voters understand voting rules, regulations, and procedures. Voters can also obtain blank ballots over the internet that can be filled out manually and physically mailed back.

Those in the military or overseas should avoid online voting and opt for the old-fashioned approach: receive their ballots by mail early, print them out, physically mark them, and then mail them back to election officials.

“For some overseas and military voters Internet voting may seem more convenient, but until technology advances to a point where it can be done securely, the risks are overwhelming and it should not be an option,” the authors wrote. “Our elections are too important to gamble on.”

Read the full report below: