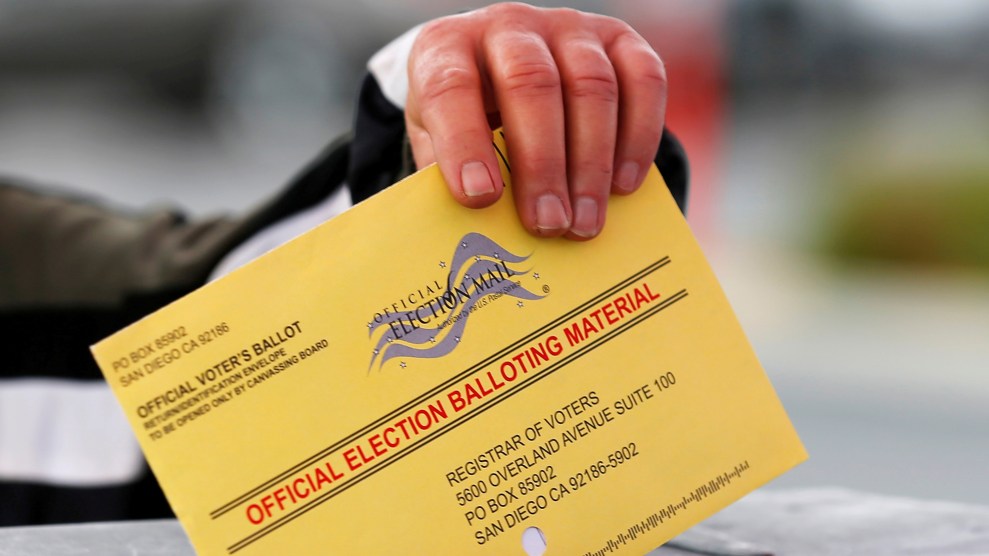

Mike Blake/Reuters via ZUMA Press

Alabama is the latest battleground in the fight to restore voting rights to millions of Americans who will not be able to cast ballots in November because of prior felony convictions.

A new lawsuit filed in an Alabama district court challenges a provision in the state’s constitution that permanently disenfranchises some felons—including those who have served their full sentences—and requires others to pay fees in order to restore their voting rights. The lawsuit, filed Monday on behalf of several Alabama residents with prior felony convictions, argues that these restrictions violate the Voting Rights Act and discriminate against African Americans, who are disproportionately disenfranchised by them.

“Citizens with past felony convictions work and pay taxes and should have a say in deciding their community’s and the nation’s laws that directly impact their lives,” said Gerry Hebert, executive director of the Campaign Legal Center, which is representing the plaintiffs in the case along with the Voting Rights Institute and the law firm Jenner & Block.

In Alabama, Republican Gov. Robert Bentley signed legislation in June that makes it easier for some felons to register to vote, but the process remains overly burdensome, the lawsuit argues. Felons who have completed probation and parole can register to vote as long as they affirm—under penalty of perjury—that they did not commit crimes of “moral turpitude,” a legal concept referring to conduct that opposes community standards of morals. But the lawsuit argues that this concept remains vague and undefined by the state, leaving many people unsure whether they can register. To find out, they can petition the state for an eligibility certificate for voter registration, but only if they’ve paid all the fines and restitution associated with their sentence. “This requirement is nothing more than a modern day poll tax that disproportionately excludes black voters from franchise,” the lawsuit says. The law disenfranchises about 15 percent of all black adults in Alabama (more than 130,000 people), according to the plaintiffs’ lawyers.

“Felony disenfranchisement laws have the undeniable effect of diminishing the political power of minority communities,” said Danielle Lang, an attorney for the Campaign Legal Center. She explained that these laws began with “the racially discriminatory policies of the Jim Crow era,” and “continue to primarily harm people of color and distort our democracy.”

Nationally, more than 5.8 million people with a felony on their record will not be able to vote in November, according to the Sentencing Project, a criminal justice research organization. About 2.2 million African Americans, or 7.7 percent of black adults in the country, have been disenfranchised because of a felony charge, the organization notes; that compares with 1.8 percent of the rest of the population.

“The biggest form of voter suppression is mass incarceration,” says Timothy Lanier, one of the plaintiffs in the Alabama case, noting that “the overwhelming majority” of those who are denied voting rights due to felony convictions are “black men, like me.”

Voting rights for felons have become an important issue during the campaign season, as states across the country debate their own laws. In July, the Virginia Supreme Court nullified an executive order by Gov. Terry McAuliffe that had restored voting rights to more than 200,000 felons. Meanwhile, California’s Legislature passed a law in August that would allow felons in county jails to vote in state elections. Alabama is one of 12 states that permanently disenfranchise some or all people who have been convicted of felonies, regardless of whether they’ve completed their sentences, according to the lawsuit.

“Something needs to be done,” adds 60-year-old Larry Joe Newby, another plaintiff in the Alabama case who was convicted in 2003 of receiving stolen property and completed his parole in 2016. “You do your time, you pay your debt to society, so you ought to be able to return back home…and be able to speak freely and vote freely.”