One spring morning this year, Darlene Lomax was driving to her father’s house in northwest Philadelphia. She took a right onto Germantown Avenue, one of the city’s oldest streets, and pulled up to Germantown High School, a stately brick-and-stone building. Empty whiskey bottles and candy cartons were piled around the benches in the school’s front yard. Posters of the mascot, a green and white bear, had browned and curled. In what was once the teachers’ parking lot, spindly weeds shot up through the concrete. Across the street, above the front door of the also-shuttered Robert Fulton Elementary School, a banner read, “Welcome, President Barack Obama, October 10, 2010.”

It had been almost three years since the Philadelphia school district closed Germantown High, and 35 years since Lomax was a student there. But the sight of the dead building, stretching over an entire city block, still pained her. She looked at her old classroom windows, tinted in greasy brown dust, and thought about Dr. Grabert, the philosophy teacher who pushed her to think critically and consider becoming the first in her family to go to college. She thought of Ms. Stoeckle, the English teacher, whose red-pen corrections and encouraging comments convinced her to enroll in a program for gifted students. Lomax remembers the predominantly black school—she had only one white and one Asian American classmate—as a rigorous place, with college preparatory honors courses and arts and sports programs. Ten years after taking Ms. Stoeckle’s class, Lomax had dropped by Germantown High to tell her that she was planning to become a teacher herself.

A historic Georgian Revival building, Germantown High opened its doors in 1915 as a vocational training ground for the industrial era, with the children of blue-collar European immigrants populating its classrooms. In the late 1950s, the district added a wing to provide capacity for the growing population of a rapidly integrating neighborhood.

By 1972, Lomax’s father, a factory worker, had saved up enough to move his family of eight from a two-bedroom apartment in one of the poorest parts of Philadelphia into a four-bedroom brick house near Germantown. Each month, Darlene and her older sister would walk 15 blocks to the mortgage company’s gray stucco building, climb up to the second floor, and press a big envelope with money orders into the receptionist’s hand. The new house had a dining room and a living room, sparkling glass doorknobs, French doors that opened into a large sunroom, an herb garden, and a backyard with soft grass and big trees. Darlene and her father planted tomatoes and made salads with the sweet, juicy fruit every Friday, all summer long.

To the Lomax children, the fenceless backyard was ripe for exploration, and it funneled them right to the yards of their neighbors. One yard belonged to two sisters who worked as special-education teachers—the first black people Darlene had met who had college degrees. As Lomax got to know these sisters, she began to think that perhaps her philosophy teacher was right: She, too, could go to college and someday buy a house of her own with glass doorknobs and a garden. She graduated from Rosemont College in 1985, and after a stint as a social worker, she enrolled at Temple University and got her teaching credential.

On February 19, 2013, Lomax was in the weekly faculty leadership meeting at Fairhill Elementary, a 126-year-old school in a historic Puerto Rican neighborhood of Philadelphia where she served as principal. A counselor was giving her report, but Lomax couldn’t hear what she said. She just stared at her computer screen, frozen, as she read a letter from the school superintendent. She read it again and again to make sure she understood what it said.

Then, slowly, she turned to Robert Harris, Fairhill’s special-education teacher for 20 years, and his wife, the counselor and gym teacher. “They are closing our school,” she said quietly. They all broke down weeping. Then they walked to the front of the building in silence and unlocked the doors to open the school for the day.

Five miles away, as Germantown High School prepared for its 100th anniversary, its principal was digesting the same letter. In all, 24 Philadelphia schools would be closed that year. These days, when Lomax visits her father in the house with the glass doorknobs, she drives by four shuttered school buildings, each with a “Property Available for Sale” sign.

Back when Lomax was a student in Philadelphia in the 1970s, local, state, and federal governments poured extra resources into these racially isolated schools—grand, elegant buildings that might look like palaces or city halls—to compensate for a long history of segregation. And they invested in the staff inside those schools, pushing to expand the teaching workforce and bring in more black and Latino teachers with roots in the community. Teaching was an essential path into the middle class, especially for African American women; it was also a nexus of organizing. During the civil rights movement, black educators were leaders in fighting for increased opportunity, including more equitable school funding and a greater voice for communities in running schools and districts.

But today, as buildings like Germantown High stand shuttered, these changes are slowly being rolled back. In Philadelphia and across the country, scores of schools have been closed, radically restructured, or replaced by charter schools. And in the process, the face of the teaching workforce has changed. In one of the most far-reaching consequences of the past decade’s wave of education reform, the nation has lost tens of thousands of experienced black teachers and principals.

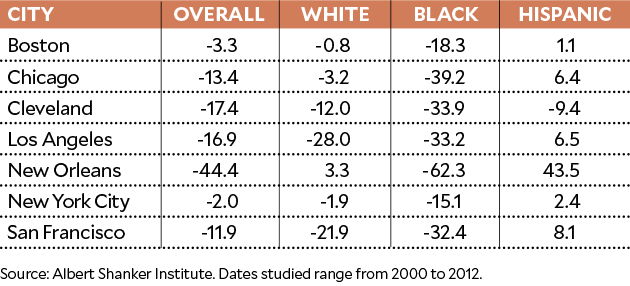

According to the Albert Shanker Institute, which is funded in part by the American Federation of Teachers, the number of black educators has declined sharply in some of the largest urban school districts in the nation. In Philadelphia, the number of black teachers declined by 18.5 percent between 2001 and 2012. In Chicago, the black teacher population dropped by nearly 40 percent. And in New Orleans, there was a 62 percent drop in the number of black teachers.

Percentage Change in Teacher Population by Race and Ethnicity, 2002-2012

Many of these departures came as part of mass layoffs and closings in schools with low test scores, a policy promoted with federal and state dollars since 2002. In Chicago, 49 out of about 500 schools were closed in 2013, and in Washington, DC, 38 out of 111 schools have been shuttered since 2008. And since 2002, 140 out of roughly 1,800 New York City schools have closed. In each of the nine cities the Albert Shanker Institute studied, a higher percentage of black teachers were laid off or quit than Latino or white educators. Nationwide, according to the federal Department of Education, African Americans made up 6.8 percent of the teaching workforce in the 2011-12 school year, down from 8.3 percent in 1990. (Nearly 83 percent of the teaching workforce in 2011 was white, down slightly from 1990.)

In all, that means 26,000 African American teachers have disappeared from the nation’s public schools—even as the overall teaching workforce has increased by 134,000. Countless black principals, coaches, cafeteria workers, nurses, and counselors have also been displaced—all in the name of raising achievement among black students. While white Americans are slowly waking up to the issue of police harassment and violence in black communities, many are unaware of the quiet but broad damage the loss of African American educators inflicts on the same communities.

“You have to expel him,” said the teacher who marched into Darlene Lomax’s office, a small, windowless room in the back of Fairhill Elementary, one morning in 2011. She set a red Swiss Army knife on the dark brown linoleum desk, next to the pictures of Lomax’s children. The teacher had taken the knife from a fifth grader who was showing it to a classmate. “I never want to see him in my class again,” the teacher, who is white, told Lomax.

Soon afterward, Lomax sat down with the 12-year-old. He told her that on his way to school, an older and more popular boy had shown him the knife and chosen him to carry it for a few days. Lomax had known the student, who was African American, for two years. She knew he struggled academically and socially, that he yearned for ways to raise his status among peers.

After talking to the parents, Lomax decided that the boy, who hadn’t had any previous discipline problems, wasn’t a threat. She suspended him and filed a report with the district. The teacher, as Lomax recalls it, argued that the district’s code of conduct required expulsion for any student who brought a weapon to school, but Lomax told her, “We have to judge each case on its merits. My judgment and common sense tells me these rules don’t apply in this case.” She added, “This child made a mistake, but he deserves a second chance.”

Within the next two years, the student turned out to be one of the higher-achieving kids in the school.

It’s well documented that black students are disciplined and punished in school at a disproportionate rate. In a 2015 study, Adam Wright, a researcher at the University of California-Santa Barbara, identified a key factor in that disparity: White teachers are much more likely than black teachers to find behavior problems with black students. (This difference did not show up when teachers evaluated white or Latino students.) Wright estimated that if schools doubled the number of black teachers, the black-white suspension disparity would be cut in half.

Other research points in the same direction. A 2008 study by the London School of Economics found that white teachers graded black and Latino students more harshly for the same performance, accounting for as much as 22 percent of the achievement gap between white students and students of color. Earlier this year, Johns Hopkins researchers found that black teachers are much more likely than white teachers to think a black student will graduate from high school or get a college degree—especially if the kid is a black boy. A 2016 Vanderbilt study showed that black students are about half as likely as white students to be put on “gifted” tracks, even when they have comparable test scores—but the disparity was erased when black students were evaluated by black teachers.

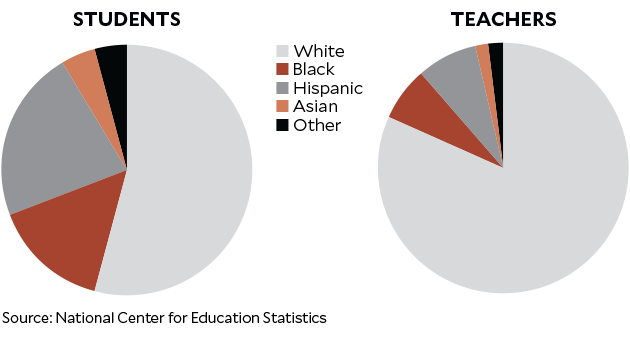

Yet, though 16 percent of America’s students are black, only 7 percent of teachers are. And even at the schools where black and Latino students are concentrated—71 percent of these students attend high-poverty, mostly urban schools—only 15 percent of teachers are black and 16 percent are Latino.

Like Darlene Lomax, Gloria Ladson-Billings grew up in Philadelphia. In the ’60s, she was a teacher there, and later a district coach working with new or struggling teachers. During that time, she remembers coming across many veteran educators who were successfully teaching kids of all backgrounds. By the early ’90s, Ladson-Billings had become an education researcher at Santa Clara University, at a time of growing concern in the field about how schools were failing children of color, especially African Americans. Ladson-Billings decided to document the teaching practices she’d seen—many of which were not in the standard education canon. She asked black parents in Philadelphia to identify teachers they considered most effective with their children and then spent two years observing those teachers in the classroom. She wrote about it in a book, The Dreamkeepers: Successful Teachers of African American Children.

Ladson-Billings noticed that instead of mentally sorting kids into “teachable” or “problem student” categories, as researchers have found many teachers do, these educators set a high bar for all students and then helped individual kids to meet it. And instead of a one-size-fits-all approach, they used different techniques with kids of varying skills and interests.

The successful teachers Ladson-Billings studied also created bonds that resemble family. That was what Lomax did when she first became an assistant principal: She invited parents, teachers, and students to come to school on a Friday evening with sleeping bags and blow-up mattresses. Teachers and parents set up a movie room in the library. Parents brought a potluck dinner, and kids, mothers, grandmothers, aunts, cousins, and teachers chatted into the wee hours. Lomax’s mother and two daughters spent the night too. “People just got to know each other better, and the overall climate of the school changed,” Lomax recalls.

Researchers like Ladson-Billings argue that teachers are more effective when they get to know their students’ backgrounds, including cultural rules for engagement and different ways of expressing knowledge. For example, instead of pushing children to stop using African American vernacular, they might encourage students to translate their favorite hip-hop lyrics into formal English—treating them as bilingual rather than as poor speakers.

Another habit of successful teachers, Ladson-Billings observed, was giving students agency and authority. When Lomax became a principal, she created “administration jobs” for students: They worked as counselors, nurses, teaching assistants, and security guards, and they used credits they earned to bid on computers, bicycles, and skateboards that Lomax would purchase with her own funds and donations. Students worked alongside the staff and advised Lomax and her colleagues on how to improve everything from lunch hour to after-school activities. The program helped build better relationships between students and staff, and it even reduced suspensions.

A focus on inclusion must go beyond classroom changes, Ladson-Billings argues, to school staffing (so students don’t see a workforce where, for example, teachers and administrators are mostly white and custodians and cafeteria workers are mostly black) and student opportunities—so that advanced classrooms aren’t dominated by white and Asian American students while remedial classes are filled with black and Latino kids. Ultimately, researchers have found, for schools to raise achievement, they have to push back against damaging racial prejudices in every aspect of what they do. Personal humiliation and discrimination are daily realities for most black students, they point out, but teachers can counteract this with inclusion, knowledge, and skills that help kids persevere.

Many of the historically segregated schools that successfully educated black students long before the civil rights era were focused on countering racial stereotypes and instilling pride, according to Theresa Perry, a professor of Africana studies and education at Simmons College. This crucial function was rolled back during desegregation, Perry writes, when researchers estimate that nearly 40,000 black teachers and principals (close to half the African American teaching force) lost their jobs. This happened even though they often had more credentials and teaching experience than white educators, according to new research from Jim Crow’s Pink Slip, a forthcoming book by Leslie Fenwick, dean emerita of Howard University’s School of Education. In the South, in particular, the consolidation of black and white schools typically meant that white school boards and superintendents had more control than black principals over individual schools’ staffing.

Lomax knows from experience how just one teacher can encourage a student to use her voice and overcome challenges. After Lomax graduated from Germantown High in 1981, she enrolled at Rosemont College, a small liberal-arts school outside Philadelphia. Of roughly 600 students, fewer than 10 were black. All the professors were white.

During her first week at Rosemont, Lomax recalls, she was standing in line in the cafeteria when she overheard a white girl say to her friend, “I didn’t know they allowed niggers in here.”

“Who are they talking about like that?” Lomax thought to herself as she looked around. “I never heard racial epithets living in Germantown, and it took me a minute to realize: They are talking about me.”

Weeks later, one of her English professors asked her, “Where did you learn to write so well?” The professor added that black students didn’t usually know how to write research papers.

The person who helped Lomax persevere was another English professor she turned to, crying, one day after an insulting comment in the classroom. “What would you like to see changed?” the teacher said. Lomax replied that she wanted to recruit more black students and professors, and perhaps launch a black student union. The teacher, who was white, helped Lomax write a proposal that Lomax delivered to the dean herself. The number of black students at Rosemont increased over time, and Lomax told me the experience left her committed to becoming a teacher and helping make schools more inclusive.

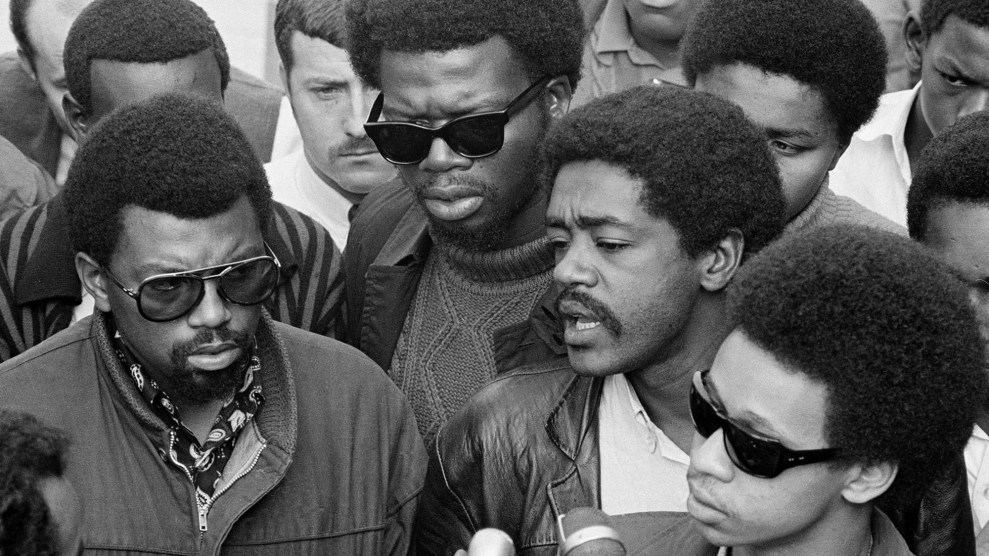

It was a little before 10 a.m. on November 17, 1967, when about 200 students walked out of Germantown High, wearing the school’s green and white colors along with gold Black Power buttons, and started marching down Germantown Avenue. A few miles up the street they met up with other marchers, and by noon the crowd had swelled to more than 3,500 students and teachers from a dozen high schools, all marching toward the Board of Education building.

By then, the student body of Germantown High—once home to mostly white immigrant students—had become more than two-thirds black. Migration from the South had increased Philadelphia’s black population from 5 percent in 1910 to 34 percent in 1970. Many black families had moved to Germantown and neighboring Mount Airy, the city’s only two integrated neighborhoods. Yet most teachers at Germantown were white, as were all the district administrators, and dropout rates were three times higher for black students than for whites.

Schools like Germantown High, historian Matthew J. Countryman writes in his book on the civil rights struggle in Philadelphia, Up South, offered a unique space for organizing because they blurred the class lines in the black community. “Corner kids,” nerds, cheerleaders, civil rights advocates, and black teachers came together to push for political power and economic opportunity.

When the student protesters reached the towering art deco Board of Education building, Superintendent Mark Shedd—a strong advocate of integration who had enrolled his own white children in majority-black schools in Germantown—invited a delegation of them into a room overlooking the crowd below. They presented their demands: black-studies classes, more black teachers and principals, a bigger voice for black parents in school governance, recognition of black student unions, and no more police officers in schools. After hours of negotiations, a student opened the window to yell to the marchers that the district had agreed to 24 of their 25 demands.

Following the march, the number of black teachers in Philadelphia’s public schools slowly increased. Gloria Ladson-Billings came home to Philadelphia the next year, after the district sent a recruiter to her college in an effort to attract more black teachers with community roots. She was first placed in a predominantly white school where, she recalls, some white parents told the principal they would not tolerate black teachers for their kids. The principal refused to transfer the kids—taking a stand that, Ladson-Billings recalls, was still controversial at the time.

Shedd created the first black-studies department in the district, called for black-history classes in all high schools (an order that wasn’t implemented until 2005), and hired black district administrators. It was a heady time, Ladson-Billings recalls, when teachers were treated as intellectuals rather than testing proctors following a script. “That environment doesn’t exist anymore,” she reflected.

Like many black educators, Ladson-Billings viewed teaching as a way to help her community. But the profession also served as a critical avenue into the middle class. In the ’50s, about half of all college-educated African Americans went into teaching—one of the few fields open to black professionals, especially women. And through the second half of the 20th century, public-sector jobs in education, social work, transportation, and the Postal Service formed the backbone of the black middle class. As Mary Pattillo, a professor of African American studies at Northwestern University, explains, affirmative action was applied most vigorously in the public sector, and to this day public jobs remain the single most important source of employment for black workers. (Not coincidentally, black workers have the highest percentage of union membership of any group.) The public sector employs a higher proportion of black workers in higher-paying jobs. And when public-sector jobs are shifted to the private sector, they typically result in longer, irregular hours and more unstable pay, reducing the assets of the black community, Pattillo explained.

Access to these middle-class jobs has a big ripple effect in black communities, Pattillo documents in her book Black Picket Fences, because African American professionals are more likely than other groups to also support family members and friends in poverty. One study in the ’90s found that black middle-class women reported a greater sense of responsibility for people outside their nuclear families than white middle-class women did. Black middle-class families are much more likely than white families to live near poor black families, and they are often key to supporting community institutions. And, research shows, black teachers contribute to communities in myriad crucial but less visible ways—as role models of college-educated professionals, resources for parents on how to navigate the school system and demand improvements from local politicians, and mentors for neighborhood kids long after the school day ends.

As Ladson-Billings left Philadelphia once more to pursue her Ph.D. at Stanford University in the early 1980s, the political winds were changing. Ronald Reagan had been elected president, and one of his first education policy initiatives was to commission a report on K-12 schools. Titled “A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Educational Reform,” it documented a growing unease with public schools among the business community and blamed lagging student performance for America’s troubles in the global market. The report called for more data-driven teacher evaluations and an emphasis on standardized testing—postulating (though with scant evidence) that test scores in reading and math would predict workplace performance.

The ideas set forth in “A Nation at Risk” would prove deeply influential, inspiring reform efforts all the way to the 2001 No Child Left Behind Act, President Barack Obama’s Race to the Top initiative, and the Common Core guidelines now being rolled out. The policies influenced by the report—including mass layoffs in schools that fail to raise their scores fast enough—have had a disproportionate impact on large urban districts like Philadelphia where most black teachers work. These reforms also laid the groundwork for the explosion in charter schools, which have attracted a less diverse teaching corps in some large urban districts (though nationwide, charters employ more African American teachers than traditional schools).

And while this wave of reformers has emphasized reducing the “achievement gap” between white students and those of color, it did not push as hard for integration and equitable funding. As a result, urban school administrators found themselves increasingly chasing scarce state and federal dollars tied to standardized test scores. In 2014, the Center for American Progress found that students in urban elementary schools spent 75 percent more time on average taking district-mandated tests than their suburban counterparts did—in large part because the stakes for their schools were so high. Multiple-choice questions became a major part of the daily curriculum.

With public sentiment increasingly critical of schools and teachers, many states rolled back education funding. In 1992, Pennsylvania began to decrease its share of district funding in Philadelphia, ultimately prompting David Hornbeck, then the city’s superintendent of schools, to file a lawsuit arguing that the state had discriminated against students of color. The state’s Republican-controlled Legislature responded in 2001 by authorizing a state takeover of the Philadelphia schools and barring the city’s teachers from striking. Hornbeck resigned—because, he told NPR in 2013, lawmakers falsely assumed that the budget crisis was a result of waste and inefficiency, not chronic underfunding and segregation.

The state created a five-member School Reform Commission—three members were appointed by the governor and two by the mayor—to fix the schools. In 2010, Republican Tom Corbett became governor, bringing with him a political network full of private-sector reform advocates. He cut the state education budget by another $860 million, and the following year Philadelphia lost $105 million more in state funding, plus $200 million in federal dollars.

To solve the budget crisis, the School Reform Commission hired the Boston Consulting Group, a private consultancy that advised the district to close 64 schools, continue expanding charters, and gut the central office. The group’s $2.6 million consulting fee was paid with private donations, including more than half from charter and voucher advocates.

By the 2013-14 school year, the Philadelphia district had 3,885 fewer staff members—teachers, nurses, counselors, secretaries, and aides—than it had at the end of 2011, a decrease of 16 percent. About 1,486 of these departed employees were teachers, and close to a quarter of them were black. Germantown High and Fairhill had to cut art, music, and physical education classes, and full-time nurses. Fairhill lost a nurse who had worked in the community for 20 years. “She was so important to our middle school students, going through a lot of physical and emotional changes, or some dealing with sexual abuse or parents’ drug addiction, all kinds of pain,” Lomax told me. “And she was just extraordinary in knowing when to intervene beyond her job duty.”

A few months before Germantown High’s closure, two seniors decided to make a video documenting the reactions of students and staff. They pointed their camera at Ismael Jimenez, who taught black history and lived in Germantown with his wife and children. In middle school, Jimenez had briefly attended a mostly white school in the suburbs, but after several racially charged incidents his parents moved him back to Philadelphia schools. He’d become a teacher, he said, to help black kids feel more at home in school. Jimenez was in the process of buying a house in Germantown and told me he had hoped to teach and live in the neighborhood for the rest of his life.

“How do you feel about the closing of Germantown?” a student asked.

“I think the closing of Germantown is a reflection of the overall destruction of public education that is occurring all over our nation in almost every inner city—from Detroit to Atlanta to Chicago to New Orleans,” Jimenez said before pausing to hold back tears.

The students turned off the camera and then turned it on again.

“The closing will affect the feeling of the community with such a large, empty building in the middle of the neighborhood,” Jimenez continued. “Parents might send their child to a charter school that may not produce better results, but on image, it looks better. And the parent says, ‘It doesn’t matter that kids around my way don’t have a local public school to go to as long as my child is okay.’ That individualism is destroying this community—and all communities—that once was the very foundation of what we needed to get by.”

“There are so many layers to this pattern of destruction,” Robin Roberts, the parent of three children in Philadelphia’s public schools and a physical therapist for the district, told me. “Germantown is such a tight-knit, established community. There is old blood. Collected history. Gorgeous brownstones. And you rip that school out, leaving a huge open lot. No security. It’s dead energy, and it invites people and events that you have no control over. Property values of folks living there go down. When a community has a vibrant, living, interactive school, property values increase. Houses look better. All of these closures—it’s erasure of history of these established communities.”

For reform proponents like Philadelphia Superintendent William Hite, restructuring was the only possible way to close a $304 million budget hole decades in the making. And he wasn’t alone: Superintendents across the country have faced similar budget holes, exacerbated by the recession of 2008 and 2009. Between 2010 and 2015, federal aid to high-poverty schools shrank by 11 percent. And in 2014, 31 states were still giving out less education funding per student than they had the year before the recession.

The Philadelphia School District spends less per student—$12,570 in all—than most of its big-city peers in the country, including Detroit, Baltimore, and Milwaukee. And until this year, Pennsylvania was one of three states that didn’t have a “weighted” formula to send extra funding for students who live in poverty, struggle in school, or are learning English. Meanwhile, child poverty rates in Philadelphia are some of the highest in the nation.

Hite is part of a cadre of superintendents in large urban districts—including Antwan Wilson in Oakland, California, and former Los Angeles schools chief John Deasy—who have been trained in an academy financed by the philanthropist Eli Broad, whose foundation in 2009 issued a handbook on how to “rightsize” school districts. Like other Broad-trained superintendents, Hite has closed traditional schools and expanded charters. “We are making these changes because we believe they will result in a system that better serves all students, families and stakeholders,” Hite wrote in his email to Lomax and other principals announcing the school closures.

“Closing schools is always hard, but we are making those decisions because there are no children in those schools,” Hite told me. “You can’t operate buildings that are designed for students when there are no students there. Given our fiscal challenges, we had to do everything within our control to ensure that we were impacting classrooms the least. You can’t operate an infrastructure designed for 200,000 students when you only have 137,000 students.” (In Philadelphia, the number of kids in traditional schools has shrunk by 50,000 since 2003, while enrollment in charters has gone up by 40,000.)

A former teacher and principal, Hite, who is black, grew up in Richmond, Virginia, and went to a school much like Germantown High. Such schools did enough to prepare students to make a living back in the ’70s, when manufacturing jobs were plentiful, Hite told Philadelphia magazine earlier this year. “Reading, writing and arithmetic—you may not have needed more than that to sweep floors in a tobacco warehouse. And it would pay you $18 an hour…Now those jobs aren’t available.”

In Hite’s view, the new economy requires schools that are much more rigorous, but the government doesn’t want to fund them. The answer, he and other reformers have argued, is a “portfolio model”: a menu of publicly and privately run schools, including charters that can attract private funding and are unconstrained by district and teachers’ union rules.

This is not an uncommon view: Even Derrick Bell, the legendary former NAACP lawyer who handled hundreds of desegregation cases in the ’60s, described charters as a promising alternative in his 2004 book, Silent Covenants: Brown v. Board of Education and the Unfulfilled Hopes for Racial Reform. Bell came across many nominally integrated districts where black and Latino students attended the same schools as whites but were placed into separate and less challenging classes. He viewed charter schools as one remedy for that, in addition to a continued push for integration and more equitable funding. Many black educators such as Geoffrey Canada, the founder of the Harlem Children’s Zone, opened charter schools as a way to break free from the constraints of the traditional school system.

But the way this push played out in Philadelphia and many other large urban districts wasn’t quite as these advocates had envisioned. First, when the state of Pennsylvania took over Philadelphia’s schools in 2002, it embarked on what was then the nation’s biggest experiment in private management of public schools: It contracted out 46 schools with low test scores to seven private for-profit and nonprofit organizations. Four years later, when this venture had failed to produce better results, the state ended the experiment and doubled down on the expansion of charter schools instead. Last year, 35 percent of kids in the city went to charter schools.

The growth of charters, though, put even more stress on the strained district budget. In Philadelphia, 30 percent of all charter students now come from outside the district, and while per-student public money follows them, the city has extra costs (such as transportation) that aren’t offset. Meanwhile, costs in traditional schools—building expenses, salaries for teachers and principals—don’t go away when a student leaves for a charter school. In all, the Boston Consulting Group estimated that each new student in a charter school creates as much as $7,000 in additional costs for the district.

But the challenges are more than financial. A growing number of educators argue that charters can’t replace what traditional schools provided, including a teaching corps with the experience and community connections to help students from every background. For one thing, charters tend to attract the students most equipped to succeed: One study found that students with severe needs—those who have been in foster care or involved with the juvenile justice system, or whose families are on welfare—are concentrated in traditional public schools in Philadelphia. Traditional schools also educate 10 percent more students living in poverty, 4 percent more English learners, and 2 percent more students with special needs. Some charter schools have even been found to practice “skimming”—illegally screening out potentially challenging students, including those with special needs, according to a 2013 Reuters investigation.

Hite argues that the concentration of students with special needs and those living in deep poverty requires schools to reorient what they do, adding that the savings from closing buildings helps the district do that. “Next year, for the first time all of our schools will have at least one counselor, no matter the size,” he told me. “They will have a school nurse. And we will be making a $440 million investment into neighborhood community schools with an attempt to address [poverty] factors.”

But many black parents and teachers in Philadelphia and elsewhere remain concerned that these changes don’t reverse the broader trend of underfunding at a time of growing need. And the increasing role of state government, and of the companies and foundations that have promoted private management and charter schools, represents to them an erosion of the civil rights movement’s gains in political power for black communities.

“The current language of educational reform emphasizes racial ‘achievement gaps’ and ‘underperforming schools’ but also tends to approach education as if history had never happened,” author Jelani Cobb wrote in The New Yorker when the historic Jamaica High School in Queens, where he had been a student, was closed in 2014. Looking back at an era when busing students across neighborhood boundaries was the primary tool for integration, he noted, “Both busing and school closure recognize the educational obstacles that concentrated poverty creates. But busing recognized a combination of unjust history and policy as complicit in educational failure. In the ideology of school closure, though, the lines of responsibility—of blame, really—run inward. It’s not society that has failed, in this perspective. It’s the schools.”

Or, as Ladson-Billings writes in her book about successful teachers, “The way a problem is defined frames the universe of possible public actions.” When the problem of racial disparities in education is defined primarily in quantitative data like test scores, other factors—cultural pride, confidence, the presence of intellectual authority figures like teachers and principals in the community, the ecosystem of economically integrated neighborhoods, and access to political power—are often overlooked.

“Church used to be the center of the black community,” Roberts, the physical therapist in Philadelphia, told me, “but now as less people go to churches, school is the only remaining hub where the people in poor communities self-organize.

“We don’t want a Walmart to be the only place where we can come together. We want a public space that is run by the community.”

In May 2015, nearly 800 students, parents, and teachers came to a reunion in front of the shuttered Fairhill school building. Lomax was there—by then she had a job as a principal in another Philadelphia school, which had no administrators except for her and a secretary, and no full-time counselors or nurses or art, music, or physical education programs. Lomax spent an hour each morning filling in as a nurse, dispensing medications to dozens of students. She also doubled as a counselor and took care of administrative tasks that had been handled by assistant principals in her previous jobs. Meanwhile, more of her students were living in deep poverty. And even though she often worked late into the night, Lomax felt increasingly hopeless about her chances of succeeding in the new school.

During her 25 years in the district, Lomax felt that she’d earned the trust of her colleagues and developed relationships to get things done. But in recent years it had felt to her as if, even as her experience and skill grew, her power to control what happened in her work diminished. If test scores didn’t go up fast enough, her school closed or she was transferred to another one. After Fairhill, Lomax said, she was placed in a different school each year, with fewer and fewer resources to do the job. Eventually, she decided to leave—seven years before her official retirement date, even though that meant that her income and pension were cut by more than 50 percent. At 53, Lomax is now living off her savings and not certain if she will ever return to teaching.

“When I read that letter about Fairhill closing, I felt like someone shot me,” Lomax told me. “It’s very hard to explain just how much emotional energy it takes to improve a school. After six years of hard work together, I really felt like we were finally on the cusp of something great: Students were engaged, parents were volunteering more, teachers’ hearts were into it, and then it was shut down. I never want to go through something like this again.”

After Germantown High closed, Ismael Jimenez was unemployed for three months and then took a job in a local Afrocentric charter school. “The curriculum was very scripted, and I had to be more of a disciplinarian,” Jimenez told me. “I like to structure my classrooms around a dialogue.” The pay was lower and the hours were longer. He quit after six weeks, when he got an offer from another school.

Jimenez now drives across town to predominantly Latino Kensington High, a commute that leads him past shuttered Germantown High. Student projects and posters from the old school cover the walls in his new classroom. At Kensington, many more students live in deep poverty and have special needs, he told me. When the kids with the strongest financial or family resources leave for private or charter schools, he said, it becomes harder to teach.

Between 2001 and 2012, the share of black teachers in the district steadily declined—from 34 percent to 26 percent—and fewer new black teachers were hired, according to the Shanker Institute report. The institute also found that teachers who left the district were more senior than those who stayed. And while experience doesn’t guarantee success, research indicates that veteran teachers are more effective than rookies and key for coaching the next generation of educators.

Superintendent Hite told me his office has been focused on recruiting teachers of color since his arrival in 2012. Last year, 25 percent of teachers in Philadelphia public schools were black—well above the national average, Hite points out.

Data compiled by Richard Ingersoll, a professor of education and sociology at the University of Pennsylvania, indicates that across the country, the turnover rate for white teachers has been relatively stable at 15 percent since the 2008-09 academic year. But the departure rate for black teachers has been increasing, from 19 percent in 2008 to 22 percent in 2013—a higher turnover rate than in any other demographic.

The biggest factors teachers of color cite for leaving, Ingersoll says, are micromanagement and lack of autonomy in the classroom. Policymakers often emphasize recruitment as a way to solve teacher shortages, he told me, but retention is a much bigger issue. From 1987 to 2011, the share of teachers of color grew from 12 percent nationwide to 17 percent (though the share of black teachers has decreased in recent years). But during the same period, turnover increased among all teachers of color. This revolving door makes it hard for students to form bonds, and for administrators to solve teacher shortages. At the beginning of the 2003-04 school year, about 47,600 educators of color entered teaching; the following year, 20 percent more—about 56,000—had left teaching. “We are pouring water into a bucket with holes in the bottom,” Ingersoll says.

“There is this myth out there that black teachers leave because of our kids,” Peggy Savage, an award-winning science and math teacher with 35 years of experience in Philadelphia schools, told me. “No, it’s the adults and the lack of voice and respect that push black teachers out. Before the School Reform Commission took over, I remember having conversations with our superintendent. We felt heard. Now, all we do is testify, but no one listens.”

José Luis Vilson is a veteran math teacher in New York and the author of a book about his experience called This Is Not a Test: A New Narrative on Race, Class, and Education. “I would venture to say that the stereotype of the ‘failing’ teacher often conjures up black teachers who stick by the union rules,” Vilson says. “Whenever reformers go into communities of color, they often seek images of failure, and if a black teacher has been in this underserved ‘failing’ school for a few decades, they are viewed as a part of the problem.”

Chris Emdin, an associate professor of education at Columbia University and the author of For White Folks Who Teach in the Hood…and the Rest of Y’all Too, told me that many black educators leave because they are forced to become the kind of teachers they resented when they went to urban schools. “They want to teach in urban spaces because they want to undo that damage that they’ve experienced,” Emdin, a former teacher, told me. “They say, ‘I hated school. I want to teach math, English, science in an engaging way.’ And the minute you try to be more creative, the principal says, ‘Nope. You gotta do more test prep. You gotta follow the curriculum.’ At every turn they are being told that they can’t do what they know in their spirit and heart and soul is the right thing to do. It’s causing teachers to leave, students to fail, and it’s making these schools factories of dysfunction.”

After leaving the school system, Lomax had to give up her apartment, about 30 miles from her father’s house, with its own glass doorknobs and small garden, and move into a cheaper place in New Jersey. Her daughter had to switch from a state university to a community college because Lomax could no longer afford to pay her tuition. “Our savings and assets are dwindling,” she told me earlier this year. “It will seriously impact our opportunities to provide for the next generation.”

Her daughter, she said, had been interested in becoming a special-education teacher. “She is a natural,” Lomax said. “But she won’t do it anymore after she saw what happened to me. She works at a nursing home now.”