Asaf Hanuka

Late on a Sunday night in January, several police cruisers sped onto Rep. Katherine Clark’s street in Melrose, Massachusetts. Clark, a Democratic representative from the Boston suburb, was downstairs watching Veep with her husband. Two of her children were upstairs. When she heard the sirens, Clark darted outside to check on her neighbors. Instead, she saw police officers on her lawn, toting rifles.

Clark soon realized what was going on. A few months earlier she’d sponsored a bill to combat “swatting,” in which a harasser makes a fake emergency call to trigger an enormous police response at his target’s home—often a heavily armed SWAT team expecting a gunman or a hostage situation. Now she’d been swatted herself.

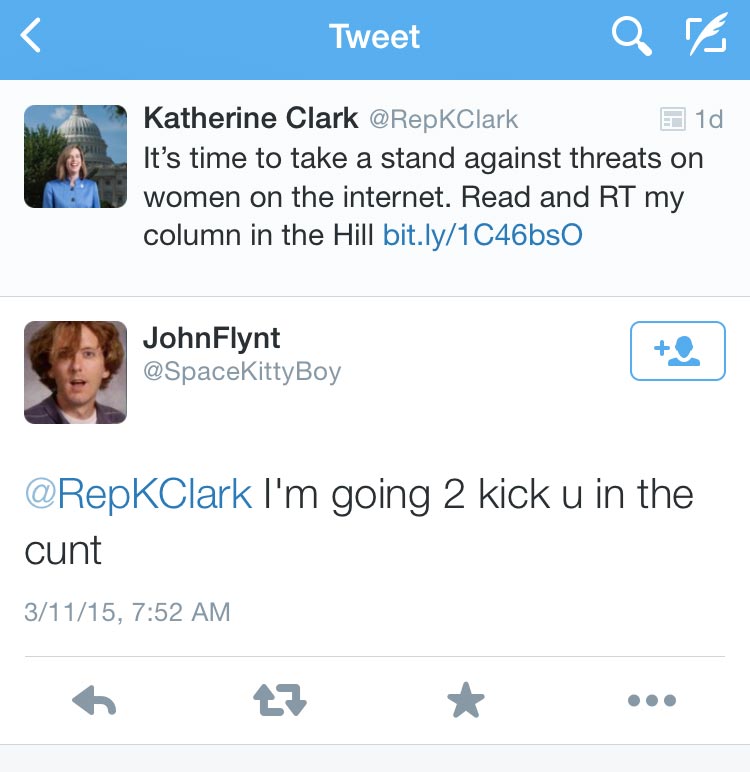

As Congress’ most vocal advocate for victims of digital harassment, Clark has sponsored five bills on the issue—she introduced the most recent one on Tuesday—lobbied tech companies, and pushed the FBI and the Justice Department to take this common form of abuse seriously. According to a 2014 Pew Center survey, about 20 percent of young women who use the internet have experienced severe online harassment. This is not garden-variety name-calling or flaming, but explicit criminal threats. “Many women we have met have had to deal with people saying they’re going to kill their children or harm their husband or rape their daughters,” Clark says. As for getting swatted with a phony active-shooter call, “the intent was probably to make me back off,” she says, “but it certainly made me more committed to continue to try to get legislation passed.”

Clark’s advocacy began in the fall of 2014, when the online harassment campaign known as Gamergate targeted female video game developers with a wave of doxxing—uncovering and posting their personal information. Brianna Wu, a prominent victim who lived in Clark’s district, received rape and death threats so “horrific and explicit” that she and her husband fled their home and eventually moved. She even hired an assistant to keep track of the thousands of threats pouring in. Wu told Clark that she’d sent these dossiers of threats to the FBI, and then…crickets. “The FBI was doing literally nothing,” Wu says. After eight months, the FBI finally responded to Wu, insisting that a formatting issue had prevented it from reading anything she’d sent. Wu re-sent the threats, but as of July she hadn’t heard anything more from the agency. In response to questions about Wu’s case, the FBI told Mother Jones that it could not comment on the specifics of an investigation, but that “the FBI takes all threats seriously and continually works with local, state, and federal partners in these investigations.”

Clark met with the FBI to discuss Wu’s case, offering to round up tools and training to help the agency tackle this sort of cybercrime. “They were pretty frank in saying that even if we had the resources, this is not where we would put them,” she recalls. “I was flabbergasted to have such a frank statement of basically saying, ‘We just don’t care about this.'”

Clark was all too familiar with this attitude. As a prosecutor in Colorado in the 1990s, she saw domestic-abuse cases that the police considered a private matter. She realized then that “we need to be working on changing the cultural perception of what is criminal behavior and what is not.” Similarly, she argues that law enforcement officials often think virtual threats “just don’t have a real-life impact.” Many don’t seem to appreciate “how devastating this can be to one’s sense of safety” and even financial stability. Clark has heard from women who’ve spent thousands of dollars on security after law enforcement didn’t adequately respond to online threats they’d received.

Following her unproductive FBI meeting, Clark ramped up her efforts to get Washington to crack down on online harassment. She brought victims of internet abuse—including game developer Zoe Quinn, Gamergate’s first target—to testify before Congress. In May 2015, Clark convinced the House to tie the Justice Department’s funding to a requirement that it go after internet stalkers more vigorously. (The Violence Against Women Act criminalized cyberstalking back in 2006, but federal prosecutors pursued about 10 out of an estimated 2.5 million instances of cyberstalking between 2010 and 2013.) Clark also introduced a bill to compel the Justice Department to enforce the VAWA provisions against internet abuse, a measure establishing a $20 million fund to better train cops and prosecutors, and another bill that would ensure broader prosecution of sextortion—using nude images to extort victims, mostly teenage girls, for money or sex. Then there was the anti-swatting bill that brought a SWAT team to her door, and this week, Clark wrote a letter to the attorney general asking the Justice Department for cybercrime numbers, and introduced a bill that would require the FBI to gather cybercrime statistics as part of its Uniform Crime Reports, a database that tracks and publishes US crime data each year.

Clark has also emphasized the connection between firearms and violence against women, and she suggested the idea for a congressional sit-in to promote stronger gun laws. In June, House Democrats, led by civil rights icon Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.), held the floor for almost 26 hours.

While Clark’s been busy, Congress has dragged its feet: All her bills were stuck in committee as of July. Then there’s the challenge of Silicon Valley. Tech companies talk about making apps that are a force for good, but male developers can be blind to how their products unintentionally abet harassment. “If you are designing a platform that is going to be used universally,” Clark says, “you have to make sure you have a diverse set of eyes that can think ahead and say, ‘This could be exploited in a dangerous way. And what are we going to build in to make sure there are ways to curb abuse of our products?'”

Wu says she hasn’t seen much progress in how the threats she still faces—or those lobbed at other women online—are handled. But in 2015, Law & Order: SVU aired an episode based on her harassment, titled “Intimidation Game,” in which a female game developer’s harassers are pursued and brought to justice. “What is very darkly funny,” Wu says, is that in the fictionalized scenario, “law enforcement heard the threats and chose to do something about it.”

This article was originally published in our September/October 2016 issue and has been updated.