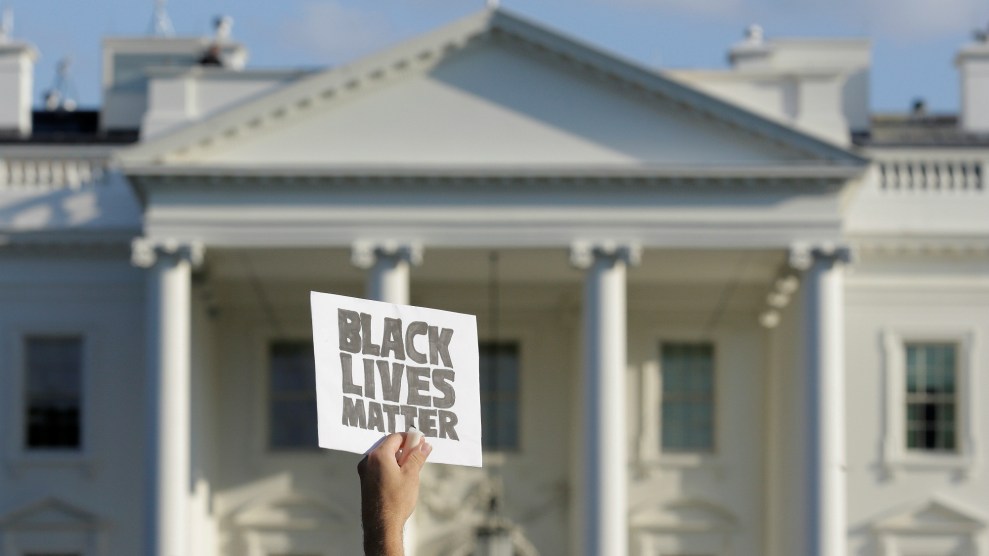

Albin Lohr-Jones/Pacific Press via ZUMA Wire

With the election one day away, it’s already clear that black voter turnout won’t reach the historic highs it set when Barack Obama was on the ballot. Early voting numbers show that fewer African Americans have cast ballots in key battleground states like North Carolina than in the past two presidential elections. Recent incidents of police violence against African Americans have done little to help, deepening the distrust of the state and disillusionment with political leaders among some supporters of the Black Lives Matter movement. And while Donald Trump has actively alienated black voters with his rhetoric, black activists have also criticized Hillary Clinton for backing the tough-on-crime policies in the 1990s that contributed to mass incarceration.

But several initiatives are trying to get African Americans to the polls by using the very language of this movement—despite its skepticism of politicians—arguing that even if some voters are unenthusiastic about the presidential race, the vote is a necessary part of building black political power and holding elected officials accountable at every level of government.

Taylor Campbell, campaign manager of #WeBuiltThis, a digital get-out-the-vote initiative focused on boosting black millennial turnout, says the campaign has tried to spread the message that voting is “an important part of our toolbox of organizing towards black liberation.” #WeBuiltThis, launched last month, has worked to reach young black voters through social media, visual messaging campaigns, and op-eds written by young black organizers on websites like the Huffington Post and The Root.

“A lot of times when folks want to engage black millennials, the way they engage is around the [presidential] election,” Campbell says. “We’re not talking about Hillary or Trump. We’re talking about the work that can be done, specifically at the state and local level, to effect change and to improve the material conditions of black life.”

Predicting the voting behavior of black millennials this year has been a challenge. Although Clinton is expected to win the overwhelming majority of the black vote, younger African Americans have been wary of her candidacy. That skepticism has fueled concerns that black turnout will be significantly lower than in 2008 or 2012—perhaps an unfair benchmark, given the enthusiasm Obama engendered. But at the same time, racial justice has moved into the spotlight as Black Lives Matter has created new outlets for black political engagement by sparking a national conversation about the role the government should play in matters of race and policing.

Those are the very issues that #WeBuiltThis and similar campaigns have highlighted, noting that voting is a way to hold politicians accountable on a wide array of issues important to black voters, from criminal justice reform to political negligence in the Flint water crisis. “There may not be excitement about politics and offices, but they understand that they have to be in the streets and the voting booth in numbers,” says Judith Browne Dianis, executive director of the Advancement Project, a civil rights organization that assisted with the development of the #WeBuiltThis campaign.

Black activists have become a particularly powerful force in local politics. Earlier this year, frustration over the delayed indictment of the police officer who shot Laquan McDonald in Chicago led to the activist-driven #ByeAnita campaign, helping to oust Cook County state’s attorney Anita Alvarez. In Cuyahoga County, Ohio, black organizers successfully denied re-election to the district attorney who failed to bring charges against the officer responsible for the death of 12-year-old Tamir Rice.

That’s the type of change Color of Change PAC Director Arisha Hatch wants to see on Election Day. In September, Color of Change PAC, the political arm of a prominent online racial justice group, began organizing Black Battleground Text-a-Thons in cities across the country, culminating in the launch of its #VotingWhileBlack voter mobilization effort last month. “We’re trying to prove that if engaged, black voters will turn out to vote regardless of if Barack Obama is on the ballot, or regardless of whether there is a presidential race,” Hatch says. Volunteers with the initiative have sent more than one million text messages to voters in battleground states. In the final weekend before Election Day, the campaign hopes to reach an additional one million people.

Whereas Color of Change PAC has emphasized the importance of local and state races, the nation’s first black president has focused largely on the presidential contest. During a Thursday speech in Florida, Obama aimed much of his message at young black voters, telling them that by going to the polls they “can bend the arc of history in a better direction.” Older black organizations like the Congressional Black Caucus have framed voting as a necessary responsibility for black youth, often referring to the battle for the vote during the Civil Rights Movement as proof of their obligation.

But that approach might be limited in its effectiveness. “The classic argument that ‘our ancestors fought and died for the right to vote’ isn’t enough and doesn’t wash with millennials,” says Dominique Apollon, research director of RaceForward, a group focused on finding innovative methods of advancing racial justice. He says that older civil rights groups would be wise to acknowledge the disillusionment young black voters feel. After the shootings of many unarmed black men and women, he says, some young people “feel that they are in a state of emergency.” Over the summer, RaceForward conducted focus groups with young black activists in an effort to understand their perspective on voting. They found that while black millennials lacked enthusiasm about the presidential election, they were interested in local races, and it was easier to engage them with local politics.

The activists of the movement surrounding Black Lives Matter have frequently accused politicians of contributing to the recent crises and of being incapable of producing real change. But in the final weeks before the election, several well-known black activists, including DeRay Mckesson and Brittany Packnett of Campaign Zero, issued endorsements of Clinton, arguing that she would be better than Trump in protecting black lives. The get-out-the-vote campaigns have not endorsed a presidential candidate, but they similarly make the case that voting can be a path to achieving the movement’s goals.

“Black voters see the struggle, and we understand what currently is at stake in our lives and our communities,” says Dianis. “We can use the ballot box as the next way to build power.”