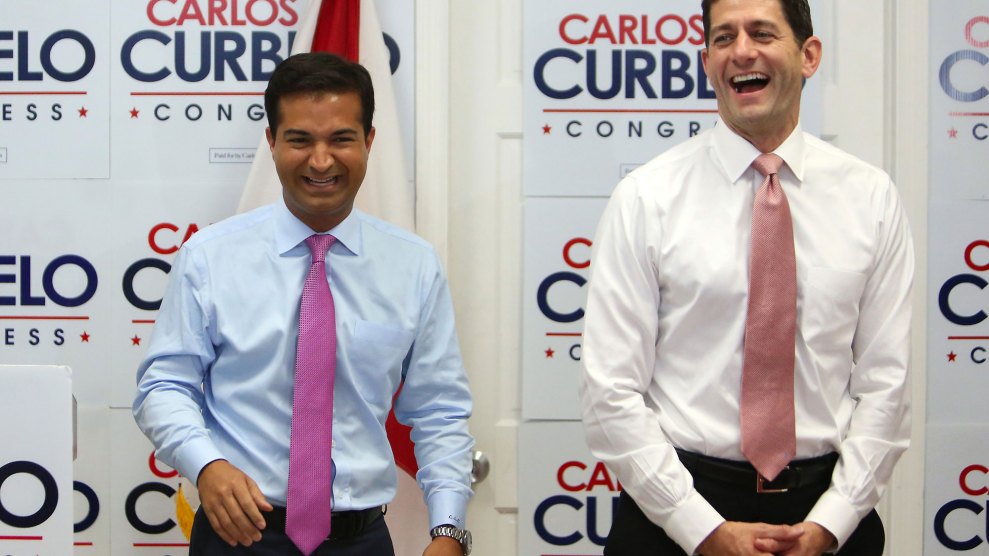

David Santiago/Miami Herald/Zuma

By 11 a.m. on the second-to-last Sunday before early voting began in Florida, Joe Garcia, a former Democratic congressman who is running to reclaim his old seat in the state’s 26th district, was going to church for the fourth time that day. “You can do one, maybe two sermons, but on the third one, you’re crying,” he said. He pulled his silver Nissan hatchback onto the grass across the street from the Greater Williams Freewill Baptist Church, a small white building amid fields of winter tomatoes in an African American neighborhood of Homestead, 40 minutes south of Miami.

Garcia is 53, with curly gray hair, glasses, and the wry smile of someone who is always on the verge of saying something he shouldn’t. His Republican opponent, Rep. Carlos Curbelo, points out that he often does. In 2013, during Garcia’s one term in Congress, he referred to obstructionist GOP colleagues as “Taliban“; in September, he told supporters that Hillary Clinton, whom he supports, “is under no illusions that you want to have sex with her.” He has run for the same seat four times and lost all but once to three different Republicans. But this fall, he believes Donald Trump will help propel him to victory.

Florida’s 26th district, which stretches from Key West to the edge of Little Havana, may be the swingiest seat in the nation’s swingiest state. The area, which was part of the 25th district before redistricting, has been represented by a different member of Congress every two years since 2008 and has flipped from red to blue to red in the last three elections. The seat is critical to Democrats’ long-shot effort to take control of the House, and to Republicans’ plans to keep it. Combined, the two candidates and their allies have spent $14 million trying to break the stalemate. What’s happening in South Florida is emblematic of the drama playing out in jigsawed districts across the country: an embattled Republican incumbent struggling to escape Trump’s shadow, and a Democratic opponent fighting to keep him there.

But the district is an outlier in a few important ways: The majority of its voters are Hispanic, nearly half its residents are foreign-born, and the consequences of global warming are already being felt. Neighborhoods flood at high tide, immigrants arrive every day, and the most divisive political fights in some communities are over the threat posed by Zika, so Florida is on the front lines of a fight that climate change may only exacerbate. In the 26th district, the future projected by atmospheric models and demographic trends is already here. The politics have evolved accordingly.

Curbelo is a GOP rising star who joined the party leadership’s whip team as a freshman. But as his party careens toward ethno-nationalism, he is waging his own campaign of mitigation and adaptation, condemning Trump’s candidacy and talking up his work as the co-founder of the bipartisan Climate Solutions Caucus in Congress. Whether or not he can survive will say a lot about what kind of future Republicans are building for themselves.

Democrats consider Curbelo’s moderation little more than a deathbed conversion, after a district he won by 3 points in the midterms was redrawn to become 3 points more Democratic. This was the message Garcia hammered home to the congregation in Homestead. He clapped along with the choir from the first pew and bounded up to a spot just below the pulpit when he was introduced. “First off, the chorus was on fire!” Garcia said. “They were on fire!”

“We’ve lived through eight years of attacks and abuse that we’ve seen on a national level,” he said. Republicans were to blame. “They have sowed this sick, sick seed. They’ve watered this wicked weed. And now comes time for their hateful harvest, and they’re running. They’re running because they’re now scared of what they did and they don’t want to be Republicans anymore, right? Because they’re scared of what they’ve wrought.” There was little doubt to whom he was referring.

Heading into the 2016 election, Miami-Dade County was the hottest place in Republican politics, home to Jeb Bush and Marco Rubio, two bilingual candidates promising a friendlier, more diverse conservatism. They were also responding to a mathematical reality: If the party didn’t become more presentable to Hispanic voters and instead continued on the course pushed by Mitt Romney (of “self-deport” fame), it would be shut out of the White House indefinitely.

They bet on the wrong hand. Trump shredded Bush and Rubio by directly confronting their appeal. He mocked Bush’s Mexican-born wife, questioned whether the son of Cuban immigrants was even eligible for the presidency, and attacked anyone who crossed him as a water-carrier for undocumented immigrants. The party shrank toward its base of white men, and South Florida became home to a large and vocal contingent of Never Trump exiles.

Calling it a “moral decision,” Curbelo promised in March, when the nomination was still up for grabs, that he would not back Trump. Rep. Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, whose majority-Hispanic district neighbors the 26th, followed suit. So did Miami Mayor Tomás Regalado, Miami-Dade Mayor Carlos Giménez, George W. Bush’s Commerce Secretary Carlos Gutierrez, megadonor Mike Fernandez, talking-head Ana Navarro, and ex-Florida GOP spokesman Wadi Gaitan. Miami-Dade was the only county Trump lost in the primary, and many of those Republican voters who pulled the lever for Rubio never warmed to the nominee; one survey of the county in October showed Trump running 18 points behind Rubio’s reelection campaign in Miami-Dade.

Refusing to support Trump is a useful survival mechanism, but by itself it might not be enough. While Republicans in South Florida have mostly hidden from the presidential race, their opponents won’t stop talking about it. The county has gained 130,000 new Hispanic voters since 2012, and of those new voters, Democrats outnumber Republicans by more than a 2-to-1 margin. The Clinton campaign is saturating the airwaves and canvassing for Democrats up and down the ballot. One irony of Trump is that the Republicans most likely to take the fall for his politics are the ones who least subscribe to them.

Curbelo is 36, with short black hair and an almost permanent smirk. Like Garcia, he is the son of Cuban immigrants; they attended the same all-boys Catholic school, Belen Jesuit, which was relocated to Miami from Havana after another alum, Fidel Castro, shut it down. Even Garcia admits to having watched his opponent’s ascent with a certain amount of awe. Curbelo spent most of his early years in politics running campaigns for local Republicans, getting elected to the school board, and supplying occasional quotes to national reporters about how the party can win with Hispanics.

He owes his current job to a series of very Florida scandals. The area’s previous Republican congressman, David Rivera, lost to Garcia in 2012 amid an investigation into whether he had tried to rig the Democratic primary by paying a fake “straw” candidate to run against Garcia. (Rivera has not been charged, but an ally was convicted for her role in the scandal.) But not long after he took office, Garcia’s campaign manager Jeffrey Garcia (no relation) was investigated for funding a fake tea party candidate to draw votes from Rivera. Jeffrey Garcia was later convicted for both the straw candidate and for absentee ballot fraud and spent time in prison. The scandals were just enough for Curbelo to squeak past Garcia in a good Republican year.

So when Trump rose to the top of the Republican primary polls last summer, Curbelo’s first response made a certain amount of sense. “I think there’s a small possibility that this gentleman is a phantom candidate,” he said in a Spanish-language radio interview in July 2015. “Mr. Trump has a close friendship with Bill and Hillary Clinton. They were at his last wedding. He has contributed to the Clintons’ foundation. He has contributed to Mrs. Clinton’s Senate campaigns. All of this is very suspicious.”

Curbelo, who first supported Bush and then switched to Rubio, has since sobered up to the reality of Trump. At his first debate with Garcia in early October, in the auditorium of their old high school with their former civics teacher looking on, Curbelo was asked out of the gate about his presidential election vote. His mind hadn’t changed. “I will not be voting for either of these two candidates because I believe we can do better,” he said.

Garcia pounced. “You know as members of Congress the only thing we do is vote—that’s the only thing we do,” he said. “The question is, what would Mr. Curbelo say to his daughters if the night of the election Donald Trump wins?”

Later, Curbelo was asked if he’d support Trump’s plan to construct a wall on the southern border. Again, Curbelo said no. When he was asked what his immigration plan would be, Curbelo offered up something that sounded a lot like Clinton’s: more money to secure the border, better visa tracking, and a path to citizenship for people who are here already. In explaining his support for that last plank, he told a story that might have gotten him booed out of the Republican National Convention, had he bothered to attend.

“I did something a few months ago, I stayed overnight at the home of someone who is undocumented,” he said. “Her name is Cristina, she has three children, one came with her to this country and two were born here. I slept over at her home and we woke up at four in the morning. I get choked up because this was one heck of an experience for me. We woke up at four in the morning and we went out and picked okra—quingombó, for those of you who speak Spanish. I was only able to do it for about three hours. She would do it for another six hours.”

Curbelo brought up Garcia’s past scandals at every opportunity, tarring, with some success, his opponent as a corrupt buffoon and a broken record. He bragged about working with Rep. Seth Moulton (D-Mass.) on gun control and Rep. Bobby Scott (D-Va.), a former NAACP official, on juvenile justice reform. If you were coming in blind, you might have thought Curbelo was a Democrat.

Garcia’s task has been to remind everyone he isn’t. In just a few days of following the race, I heard a variation of his favored retort a half-dozen times. “He’s in the Republican leadership and voted to make women wait 48 hours after they were raped [to get an abortion],” Garcia says. “He’s a guy who’s voted or tried to push back Obamacare on nine separate occasions with no replacement. He’s a guy who’s voted to block all the president’s EPA rules on clean water. But suddenly his road to epiphany, his road to Damascus, was the epiphany of the court drawing a more liberal district.”

A few days after their first debate, Curbelo and Garcia faced off again at a forum for local candidates in Key West. A hundred or so residents gathered in an auditorium above an art gallery a short walk from Ernest Hemingway’s old home. The outer Keys are Garcia’s turf; he opened a district office there when he was congressman, and the area skews heavily Democratic. But Curbelo needs Democratic votes to win, and he believes he can get them by doing something Republicans are loath to do: talk about the environment.

Just getting to the event offered a glimpse of what the future has in store. The King Tide, a semi-annual event that produces supertides similar to what regular tides will look like in a few decades, had turned roads and parking lots on both sides of the main highway into small lakes, as if a water main had burst. “I was out for a run with my dog yesterday, and I had to alternate my route because of the deep water in my street,” the Keys’ Republican state representative, Holly Raschein, told me as she gave away bottles of sunscreen before the forum. Raschein, like Curbelo, split with her party’s leaders to push for funding for adaptation.

More than an hour of the candidate forum was devoted to one issue: fighting mosquitoes and the diseases they carry, such as Zika. The most prominent campaign signs in Key West advertised seats on the mosquito control board, and two questions on the ballot in Monroe County will determine whether to allow a British company to release genetically modified mosquitoes. Opponents of the plan wore white badges that read, “I do not consent.”

Adaptation was the word of the night. Onstage, Curbelo and Garcia clashed on Trump and Cuba, but Curbelo also went out of his way to talk about his work on water and climate. He boasted of securing $2 billion for Everglades restoration, blocking future flood-insurance hikes, and sponsoring a bill with the bipartisan Climate Solutions Caucus, the working group he co-founded that now boasts 20 members. (The bill does not propose any measures to address climate change but, in Washington fashion, would create a commission to study and propose measures to address climate change.) “We’re at the tip of the spear,” he said.

Afterward, Curbelo laughed off Garcia’s talk of a politically motivated conversion. He’d been confronted with the science by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration experts and he’d accepted it. So why did most of his colleagues still have their heads in the sand? Curbelo blamed Democrats. “You’ve gotta look at the history of this issue,” he told me. “When Vice President Gore adopted this cause, that resulted in just some natural polarization on the issue, because I think a lot of Republicans wrongly assumed that this was a Democratic issue or a liberal issue. I think hopefully if Mr. Gore could do it all over again, he would find a Republican partner and advocate together, but anyway that didn’t happen.”

He told me he was optimistic that climate change legislation could happen in a Republican House. “I’ve been very happy with the response I’ve been getting from Republicans,” he said. “Remember—no one’s worked on this! Very few people have worked on this on the Republican side, so I thought it was gonna be a lot tougher, but there’s a lot of interest.”

Curbelo was even optimistic, sort of, that climate legislation might pass under a President Trump—someone who has previously said global warming is a Chinese hoax. “Who knows! I think he’s someone who’s clearly shown that he’s flexible on many issues,” he said, forcing a laugh. “Sometimes too flexible for my view, but who knows, maybe!”

But his sunny optimism about his party’s future speaks to the challenges facing Republicans like him. It isn’t true that Curbelo’s colleagues haven’t worked on climate issues—they have. But their work has been focused on blocking climate action and hounding scientists who are working on it. That level of obstruction has played well in deep-red patches of the country. But in educated, coastal swing districts, and in particular among millennial voters, it has contributed to a rising tide against Republicans. Garcia may be heavy-handed in his criticism, but his efforts to tie Curbelo to his party’s mainstream have a certain resonance; what’s the point of calling something an existential threat if you’re not even willing to pick a presidential candidate who will fight it?

Many House Republicans who have seen the light on climate change, including Illinois’ Bob Dold, Florida’s David Jolly, and New York’s Lee Zeldin, happen to be in similarly dire electoral straits. On Tuesday, thanks to losses and retirements, the number of Republican members of the Climate Solutions Caucus could easily be cut in half.

As Curbelo made small talk with a few constituents and fended off questions from the mosquito people, a middle-aged man walked up. He was a biology professor at Florida Keys Community College and a Bernie Sanders supporter, but he wanted to thank Curbelo for his work on climate—he was still on the fence about which candidate to back. Next up was Jonathan Van Leer, a professor of physical oceanography at the University of Miami. He lives just outside the district but said he’d vote for Curbelo if he could. After he’d had a few words with the congressman, he told me, “I’ve been teaching climate change for a long time, and it’s the first time I haven’t felt depressed.”

Curbelo had a three-hour drive back to Miami, but he could not leave just yet. A filmmaker had released a new documentary about the effects of climate change on South Florida, and Curbelo, stepping out of campaign mode for a minute, had agreed to say a few words about his climate caucus and the challenges that lay ahead. As he and a few staffers lingered in the emptying theater, someone had turned on the documentary, and on the screen behind them a wave came crashing down.