(Tom Gralish/Philadelphia Inquirer/Associated press

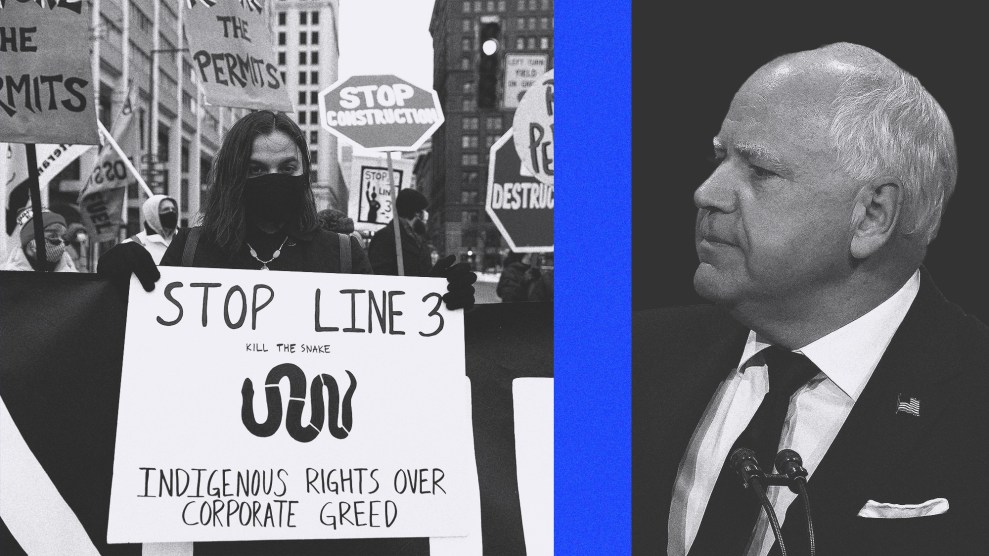

The tone of Rep. Tom MacArthur’s Wednesday town hall in South Jersey was established early on. The venue was packed, the crowd tense, and, after a series interruptions from the audience, the Republican congressman, whose amendment to the House health care bill is the cornerstone of the House Obamacare repeal bill, asked the room for respect. From somewhere in the crowd a man shouted, “Can I be disrespectful on behalf of all the people you’re gonna kill?”

Things proceeded apace from there. When MacArthur began taking questions at 6:30 p.m., hundreds of constituents were still outside, unable to fit inside the crammed rec center. When the town hall wrapped up, it was 11:30. The outrage never seemed to let up; in a district that went for Donald Trump last November by 7 points, MacArthur faced a firehose of questions (and heckling) from residents who feared for their lives and those of their loved ones, and who held the New Jersey Republican and his colleagues responsible.

Questioner, choking up, says his wife died of brain cancer two months ago. “I sell insurance…I know exactly what a risk pool is.”

— Tim Murphy (@timothypmurphy) May 11, 2017

He heard from a woman (and her sister) who had suffered from drug addiction and was worried about choosing between her health and her rent. He heard from a 17-year-old who wanted to know—”yes or no”—whether the Republican bill would allow an insurer to treat rape as a preexisting condition. (He said he would not describe rape as a preexisting condition and that “this bill does not allow discrimination in insurance based on that,” although it indirectly makes such a scenario possible.) A man whose wife died of brain cancer two months ago told MacArthur he knew “high-risk pools” included in the amendment were a sham solution because he himself worked in the insurance industry.

Next questioner tells MacArthur “this is your bill.” Before MacArthur can respond, everyone with a pre-existing condition stands up.

— Tim Murphy (@timothypmurphy) May 10, 2017

One of the night’s most intense moments came at about the three-hour mark, from a constituent of MacArthur’s named Geoff. Like others in the audience, he noted that MacArthur had initially opposed the Affordable Health Care Act in March, at the time indicating that it was too complicated and would take more time to do properly, but had subsequently offered the amendment that allows states to waive the prohibition against insurers charging more for people with preexisting conditions.

Geoff: Everyone that is gonna be losing from this you have not addressed. I don’t get any return phone calls. If I ever fax or email I get a form letter that informs me about what I contacted you about and why you can’t do anything about it because it’s still in committee. You look forward to taking my opinions into consideration. You have not taken my opinions into consideration. “Too complicated, it’s not gonna get done in months.” Three. Weeks.

MacArthur: What’s your question?

Geoff: Ooooh we haven’t even begun. I’m not done with you yet. I got the mic and I’m not going anywhere. Turn off the power. I’ve got a very loud voice. My wife was diagnosed with cancer when she was 40 years old. She beat it, but every day—every day—she lives with it. She thinks about it. Every pain, every new something going on somewhere, is it coming back? Is this cancer? Do I have it again? Is it gonna kill me this time? Is it gonna take me away from my children? Speaking of which: my children. Both have preexisting conditions from birth. One cardiac, one thyroid. You have been the single greatest threat to my family in the entire world. You are the reason I stay up at night. You are the reason that I cannot sleep. What happens if I lose my job?

You can watch that exchange here, via Politico‘s Dan Diamond:

Man angrily tells MacArthur: “You have been the single greatest threat to my family.” Says GOP bill was dead until MacArthur resurrected it. pic.twitter.com/U1O8vTwVBx

— Dan Diamond (@ddiamond) May 11, 2017

MacArthur’s response to such questions was to refer back to his own experiences with the health care system—his oldest daughter, Grace, died when she was 11, and he said it was a motivating factor in his desire to fix what was broken. For all the noise anger surrounding what he’d done, MacArthur suggested, MacArthur and his constituents were actually on the same side; he even bristled at the accusation that he was getting rid of Obamacare, even as Republicans have celebrated the bill as a “repeal” of the law. MacArthur told the town hall audience frequently that they were not representative of his Republican-leaning district as a whole, and that their preferred solution (a single-payer health care system) wouldn’t fly. As these things go, he was patient and soft-spoken; it was impossible to imagine President Donald Trump lasting 15 minutes in such an environment, let alone five hours, and most of his colleagues have taken an easier route out—just 14 of the bill’s supporters have scheduled town halls during the weeklong recess.

But the message of the evening was one that the bill’s opponents are determined to get out whether their congressman shows up or not, and it is not likely to dissipate after five hours. Outside the event and at congressional offices across the country, activists held “die-ins” to protest the estimated 24 million people who will become uninsured if it becomes law; in some districts they’ve recruited neighboring Democratic representatives to answer their questions instead. The stories MacArthur’s constituents (and others across the country) are telling at town halls are deeply personal, and bely the allegations of paid protests and outside agitators. The president’s approval ratings really are in the tank and the bill really does—as more than one attendee pointed out—enjoy the support of just 17 percent of Americans. Voters really are scared.

MacArthur may be able to relate to their pain, as one questioner conceded from the start. But none of them seemed to believe he was doing anything to stop it.