Left to right: Kimberly Ann Tucker, Linsey Jobe, Beverly Tuberville, Nicole Stratton. Gluekit

On a dreary, cold Saturday in April, Nicole Stratton was bopping around the plaza in front of the gold-domed New Hampshire Statehouse, making sure Concord’s March for Science rally was moving along. Short and lively, with shoulder-length red hair, Stratton reminded me of a spring robin. Wearing a fleece jacket, skinny jeans, and scuffed brown boots, she gave personal hellos to everyone there: upbeat, cheerful, welcoming.

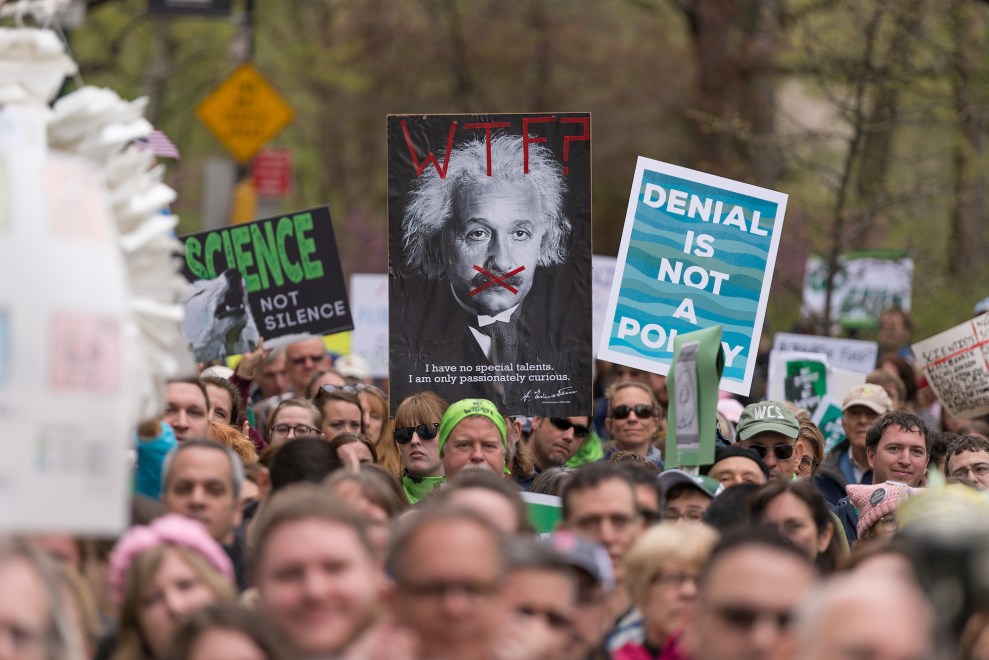

The rally, she beamed, was essentially running itself. Her volunteer marshals, in their screeching green safety vests, were assigned to their corners. Groups like the Five Rivers Conservation Trust, the New Hampshire Science Teachers Association, and the Citizens’ Climate Lobby had set up folding tables under 19th-century orator and statesman Daniel Webster’s bronze gaze. Local singers and guitarists took turns on the modest pine stage Stratton’s husband had built, using the sound system her father had rigged up. Other than the 2,000 or so marchers—overwhelmingly middle-aged, speckled with kids and dogs—downtown Concord, with its brick and granite buildings and white church spires, was mostly empty on this Saturday morning, the Legislature and its business elsewhere. That was fine with Stratton. Her goal for the day wasn’t lobbying, but getting everyone signed up and ready to do more when they got home.

Like so many other people in recent months, Stratton could never have imagined doing any of this before the election. Sure, in high school she had protested the Iraq War. But then she got married, had three kids, started working as a school special-ed assistant, and for a decade made family and career her priority. Besides, under President Barack Obama she felt safe. Then came November 9. Stratton woke up stunned that her country could have elected him. “I was just devastated,” she said. “I realized that I needed to be active, because it was my complacency that I think is to blame.” Nationally, her demographic—white women—had voted for Donald Trump, to her utter dejection. “I feel like I hadn’t spoken my mind enough. I feel like I hadn’t been represented when I should have. I should have stood up for my LGBTQ friends. I should have stood up more for the rights of immigrants and refugees when I had more of a chance.”

Two days after the election, “I brought my children and my father to this march in Manchester, and it was pretty intense, and I understood how many people were frustrated, and I just started to organize.” By the following weekend, she had planned her first rally in Concord. The weekend after that, she was at yet another demonstration, this time in Keene. By November 27, she had helped create a public Facebook page that gave followers daily action updates and kept them informed about what was happening around the state. On Inauguration Day, they became an Indivisible chapter.

Indivisible had come into being around Thanksgiving, when a couple of ex-congressional staffers, Leah Greenberg and Ezra Levin, who are married, helped write an outline of how they’d seen the tea party block Obama and posted it online. Clear, crisp, and practical, the “Indivisible Guide” laid out an easy-to-follow plan for pushing members of Congress to resist Trump’s agenda. They hoped the document would be read by a few friends and family. But soon it was being downloaded hundreds of times an hour, and the couple had to enlist scores of volunteers to help them respond to requests to be listed as Indivisible contacts. As of May 8, the guide had been downloaded or viewed more than 3 million times. Hundreds of thousands of people had signed up. Nearly 6,000 local chapters were registered—among them Stratton’s group in New Hampshire.

Becoming an Indivisible chapter was an obvious step for Stratton. The Indivisible movement drives home the message that for the duration of the Trump administration, the most important stance is resistance—and the most effective action is to let those who represent you in Congress know exactly how you feel about the Trump agenda. Call every single day, following a script coordinated with others in your group. Go to your representatives’ town halls and speak your mind. Visit your members’ local offices every week. Stiffen the Democrats’ spines, and weaken the Republicans’ resolve. Prevent Trump from destroying your country.

You’ve seen some of the viral videos that have resulted, like the town hall full of furious constituents chanting, “Do your job!” at Utah Rep. Jason Chaffetz, or the “Missing in Action” town halls in districts where GOP members of Congress refused to show up to discuss health care. And who was it who grabbed this guidebook with the desperation of the drowning? Mostly—though not only—women, many of them suburban whites catalyzed by the Women’s March. One nonscientific study of members of a group called Daily Action found that more than 60 percent of those calling Congress and swarming town halls were middle-aged women. That’s similar to the proportion of women that Indivisible chapter organizers kept saying they found in their own groups. As Beverly Tuberville, the founder of Indivisible Oklahoma, told me, “The real worker bees are those women in their 50s. That’s where I find the heart is—it’s the core of who we are.”

And they’re mostly political neophytes. Retired debt collector Helen Hronec of Dayton, Ohio, told me that though she’d always voted Democrat, she’d never been to a protest. But on January 8, she saw a Rachel Maddow report on Indivisible, “and that was it. I felt compelled.” She immediately registered a Dayton Indivisible chapter, which now has 1,147 members. “It was probably the easiest decision I ever made.” Lara Crigger, the founder of a Louisiana Indivisible chapter, had a similar experience. “I’ve never organized anything,” she said. “Not a bake sale, not a birthday party, not a D&D group, nothing.”

Kimberly Anne Tucker, a 51-year-old African American retired school administrator in Virginia Beach, Virginia, told me that “90 percent of statewide Indivisible leaders had absolutely no grassroots organizing experience.” Tuberville, an Oklahoman, grew up believing that being a Christian and being a Republican were two sides of the same respectable belief system. Then the videos of black men being killed by police opened her eyes, as did Trump’s ascendancy, and she voted for Hillary Clinton. After the election, she had a revelation much like Stratton’s: “It was people like me, people who were not paying attention to what was really happening, who created this mess. It’s our responsibility to fix it. After crying for 24 hours…the fighter in me woke up.” Downloading the “Indivisible Guide” was just the next stage of grief after the election: crying, depression, “and then, ‘Oh, hell no.'”

Historically, many political movements have been spearheaded by women, be it abolition or temperance or the Argentinian Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo. The progressive social movements boiling up over the last decade, many also organized by women, have been driven by people whose daily security is profoundly threatened: gay and transgender youth, fast-food and domestic workers, the Dreamers, Black Lives Matter. Many of the women who’ve joined Indivisible might have sympathized or even aided those activists, but they nevertheless felt secure in their personal lives. With that in jeopardy they now feel entitled—and obligated—to act. And they’re doing so by marshaling the skills they’ve learned in their professional and personal lives: If I can get a new playground put in or supervise a school system or make partner in a corporate law firm, I can hold my senator to account. All they needed was the instruction manual.

For the most part, the women I spoke to are left of center, but not by much—#ImWithHer voters rather than #FeeltheBerners. Some were part of the Pantsuit Nation; some were Republicans by habit; others were closet Democrats but not voters. Linsey Jobe, who manages a large grocery store in Waco, Texas, told me, “We have people in our group who didn’t vote. They weren’t even registered.” The idea was: “‘Why bother? I live in Texas.’ And now, at every meeting that we have, we have a voter registrar set up.”

Consider Crigger, from Louisiana, who is a financial writer with two toddlers at home and had never been to a protest until November. Now she’s coordinating a 500-person group in Louisiana’s 1st Congressional District (represented by Republican Minority Whip Steve Scalise, to whom the Indivisible chapter sent get-well wishes after he was shot on June 14). “I am definitely a centrist. I never really ‘felt the Bern’ or anything like that. I was very proud to vote for Clinton.” But Trump’s win brought up the painful memory of Crigger’s “super-duper political” best friend, who had died in 2015. Crigger was apprehensive about organizing anything—but she kept thinking about what that friend would have wanted her to do. “She would have been first in line to join the Indivisible movement. So I did it. I started up a chapter. This was a way that I could tackle the grief head-on, do something concrete.”

So why is it that ladies are leading the anti-Trump resistance? Many of the women I spoke with in their 50s and 60s felt that they finally had the time. Whether they work outside the home or not, they’re likely freed up in middle age, no longer having to drive the kids to baseball, oversee homework, keep the domestic engine running efficiently. Older women have long been the workhorses of community life, holding fundraisers, volunteering at the hospital, serving on the library committee. Indivisible is just a different place to channel that energetic overflow.

“I was doing a mean hokey pokey with my granddaughter,” Tucker, from Virginia Beach, told me. “Just enjoying time with her and [taking her to] the farms and playgroups and just really enjoying being a full-time grandmother.” Then, after the election, she saw Maddow’s report on Indivisible, and in the dark, with her husband asleep beside her, she grabbed her iPad and downloaded the guide. “I started the group right there in bed at night,” lights out, awash with both desperation and hope. “The day of the Women’s March [in Norfolk], I passed out flyers about the group, and we…Oh my goodness. Before I knew it, we had 300 members, then 500 members, and we doubled, and I couldn’t keep up with vetting people, so I had to get help, and now we have over 1,900 members.”

Monica North, a 55-year-old white woman whose kids are now in their early 20s, organized a northern Colorado Indivisible chapter. She told me, “So many people are saying to me, ‘Oh my gosh, I really wish I had more time to do something. I have to take care of my kids.’ And I’m like, ‘You know what, when I had little kids, I wasn’t doing anything. We’ve got your back.’ You know? And that’s what the retired folks are all saying: ‘Look, we’ve got time. You guys go work. We got time.'”

Others point to fury. “It wasn’t just that Hillary lost,” Tuberville, the founder of Indivisible Oklahoma, told me. “It was that she lost to a disgusting man that none of us could stand”—which felt far too familiar. “Working in corporate life, you see the jerk get the promotion when the more qualified woman is asked to pick up the coffee.” She continued: “Everyone has a Trump story, whether it’s an ex-husband or a boyfriend or a father or an uncle or a boss, especially a boss.” With the stakes so unbearably high, she had no choice but to act.

When asked whether their groups were predominantly white and middle class, most of the organizers I spoke with apologetically acknowledged that yes, that was true—in part because organizing via Facebook means reaching out to friends of friends. Given that Americans’ social networks are often pretty homogeneous, it’s no surprise that their Indivisible groups are as well. There were exceptions, of course: Alma Castillo’s El Paso, Texas, chapter is 80 percent Hispanic, surely in part because she and her brother, who first registered the chapter, are naturalized Mexican immigrants. But the white women quickly told me how hard they were working to build coalitions with those on the front lines of Trump’s attacks: immigrants, Muslims, Planned Parenthood, LGBTQ groups, anyone who needs health care.

In Virginia, Tucker told me, “I really do believe that the work we’re doing across this country with Indivisible is changing, or has the potential to change, our country in ways that are as significant as just resisting the Trump agenda. Because what we have is a group of people who went from being afraid or nervous or having never contacted a congressman by phone or email, being intimidated by the thought of going to a congressional district office, who are doing it on a weekly basis.” Now they’re monitoring their local school board and tracking the Virginia Legislature’s votes and calling city council members about kindergarten.

And nearly everyone I spoke with was recruiting talented people—often but not only women—to run for office. Such efforts are already paying off: Emily’s List, which helps fund pro-choice candidates, reports 13,000 women have contacted the group since the election, as opposed to 920 before November. And according to the Federal Election Commission, 525 new Democrats have signed up to run in the 2018 midterm elections—up 73 percent from this point in the 2014 midterms.

That includes Tucker. “At our very first meeting, I said, ‘I am not interested. There is not enough tea in China.'” But when she found out that some Republican representatives in the Virginia House of Delegates would be unopposed, she realized, “I cannot just limit what I’m doing to calling representatives—and so I decided to run.”

On June 13, Tucker won Virginia’s 81st District’s Democratic primary against another Indivisible member, with whom she had run an exceedingly collegial race, by 2-to-1. “I was ecstatic about the turnout,” Tucker told me. She said that in three months her campaign had knocked on 3,000 doors and contacted thousands more people by phone and social media—and that it will spend the summer doing still more, with the goal of upping turnout in November and flipping the district. “Democrats are very motivated right now.” All those resistance phone calls, she explained, had just whetted everyone’s appetites for change.

I recalled leaving an Indivisible meeting in Providence, Rhode Island, where I spoke with a wispy 80-year-old woman who said all these newly energized folks were going to make the nation better. “Maybe we needed Trump,” she said, before her eyebrows shot up and she clapped her hand over her mischievous grin.

Portraits from left courtesy of Kimberly Anne Tucker Campaign, Linsey Jobe, Beverly Tuberville and Katelyn Hennigar.