Marion S. Trikosko via Wikimedia Commons/White House Press Office via Wikimedia Commons

President John F. Kennedy is often credited with being a champion of civil rights, but, in fact, he was a reluctant advocate. He only delivered his famous speech describing civil rights as a “crisis” and a moral issue in 1963, after years of racial confrontations about school desegregation and violent protests in many American cities. Only when he saw the brutal attacks by Birmingham, Alabama, police on peaceful student demonstrators, egged on by the governor and the mayor, did he realize he had to speak to the nation.

For Martin Luther King Jr., Kennedy’s 1963 speech, though long overdue, was the culmination of his efforts to engage the president on the urgency of addressing the civil rights crisis taking place in America. In his new book, Kennedy and King: The President, the Pastor and the Battle Over Civil Rights, Steven Levingston, a Washington Post book editor and author of The Kennedy Baby and Little Demon in the City of Light, takes a look at the complicated, often frustrating relationship between these two leaders, and how King’s influence helped shape Kennedy’s legacy. In the end, Martin Luther King, his allies, and Robert Kennedy succeeded in pushing the reluctant president to take action. After his speech, Kennedy sent a major piece of civil rights legislation to Congress that became the Civil Rights Act of 1964, signed by President Lyndon Johnson.

Mother Jones spoke with Levingston about leadership, the relationship between these two men, what forces were at play to constrain Kennedy’s commitment to civil rights, and what, finally, made him turn the corner.

Mother Jones: In some ways the individual stories of Martin Luther King Jr. and John F. Kennedy are very well known. Why did you think it was important to connect them?

Steve Levingston: The two men had a great influence on each other. King had a tremendous influence on how Kennedy evolved during his term as president. And, in fact, Kennedy had an influence on King as well, in how King managed and pushed forward the civil rights movement, especially in late 1963. There was a real exchange going on between the two men that I felt gave a different and new picture of what the civil rights movement was in those early years of the 1960s. I wanted to understand how John Kennedy went from being a man who came into the White House uninterested in being a true advocate for civil rights, and how he became, by 1963, what you could say was our first civil rights president. I found again and again, that Martin Luther King was really instrumental in helping guide and teach Kennedy to develop the conscience, the empathy, and the moral courage to take the actions that were necessary.

MJ: Do you think JFK was a kind of unconscious racist, the way that many white people, even well-intentioned Northerners, were at the time?

SL: No, I don’t really think he was. When they were young, Robert Kennedy told a story about how, when the family was around the dinner table, they were told it was really their obligation to help those who were less fortunate than they were—because they were very fortunate. What was interesting about that is they never really talked in terms of separating the races. They really didn’t even think in terms of black and white. But at the same time, they didn’t really associate with African Americans except on a servant level. They had valets or other workers who helped them in their lives. When John Kennedy was in college, he had a valet that his father paid for who was a black man; he included that guy in a lot of his activities. There was sort of a fraternity there where he brought him in, but he didn’t bring him in too closely. It was a difficult balance, but I don’t think there was ever really a racist impulse in John Kennedy.

MJ: How did JFK get from being a reluctant champion of civil rights to becoming a civil rights president?

SL: It wasn’t easy. He was very ambivalent for a good part of the time. He was concerned about the economy and taxes and unemployment. And he was also concerned that if you moved too quickly on civil rights, his agenda would be impaired by Southern senators who did not want to move on civil rights. So, there was a bit of a trade-off. He would take small steps. He would go forward a little bit; then he would go backward again. But he listened over time and became more empathetic to the plight of the black community through the lessons that he was learning from Martin Luther King, where he really developed a sense of empathy and understanding for the plight of the individual black man and black woman and black family.

He tried to understand what it felt like to stand in another person’s shoes and see what the world looked like. And through that, gradually, in June of 1963 he went before the nation and announced civil rights legislation and talked about civil rights in moral terms. He finally come to the realization that something serious had to be done.

MJ: The title is Kennedy and King, but not just one Kennedy was involved. What was Bobby Kennedy’s role in this story?

SL: If we say Martin Luther King was instrumental in John Kennedy’s education, I think Bobby Kennedy was also. Bobby Kennedy was moving a little bit faster than his brother. Bobby was a more passionate figure. He was in some ways more inquisitive about the differences in social condition in the nation. He went out, and he wanted to learn about it in a very direct way, much more so than his brother did. In one famous incident, Bobby invited a group of black intellectuals to the Kennedy apartment in New York. He wanted to hear from them what they felt the situation was for black people in the country, but he also wanted to tell them what he felt the administration was doing.

One of the intellectuals was named Jerome Smith, and he was a veteran of the Freedom Bus Rides. He had been beaten many times and actually been hospitalized. He even had some medical conditions as a result of his activity in the protest movement. He was a young guy who started out believing in King’s nonviolent protest but had changed his tune a little bit after he had seen what had happened to him, and what was happening to the movement.

During the conversation, Jerome Smith started to speak up; he was really angry about the state of black America and what he had been through. So, he started to lay into Bobby Kennedy, and at one point he got so angry he said, “I just feel like I want to vomit being in the same room with you.”

Bobby Kennedy couldn’t believe it. He sat down, and he stared off in the distance, and he really felt hurt and confused. He didn’t really know what it was all about. Others started to lay into him, pointing out the conditions of the black community in kind of an aggressive way. Bobby Kennedy went away stunned and not knowing what to make of it. But he didn’t go away and maintain his anger. He went away and he thought long and hard about it, and he talked to people about it. And he probed his own conscience over it. And in time, he began to understand what these protesters, what these intellectuals, were trying to tell him. He began to understand and to see what their perspective was. This was a real turning point in Bobby Kennedy’s development. He brought this new sensibility into the White House, and into his discussions with John Kennedy, as well, and helped foster progress within the White House.

MJ: So what are the greatest misunderstandings about JFK and civil rights?

SL: A misunderstanding, in regard to John Kennedy—and this was really one of the fundamental starting points for my book—is that he has come down through history as a civil rights president. So much so that in many black homes over the years, there have been three portraits on the wall: Martin Luther King, Jesus Christ, and John Kennedy. But it was actually a very hard journey for him to reach that point. And we need to understand how far he came, and what help he had from people like King and others in the movement, and his own brother. He had to evolve and develop enough as president to see that real action was necessary on civil rights.

MJ: What do you think this tells us about presidential leadership?

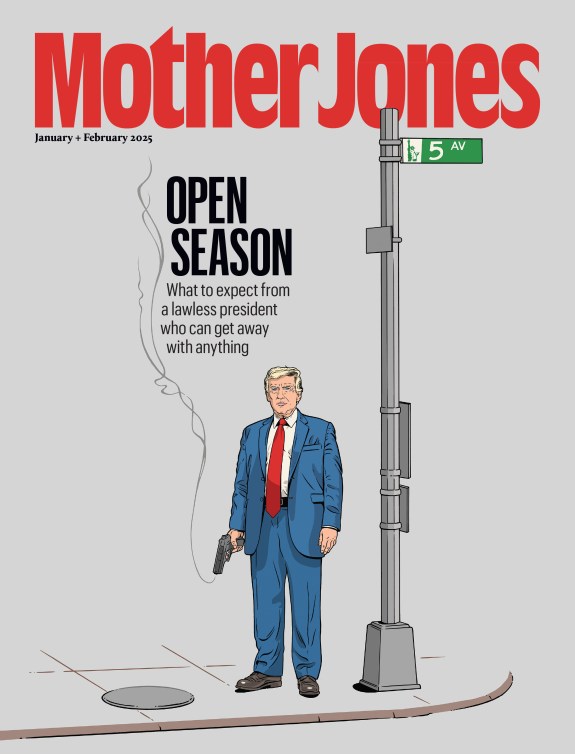

SL: History has become much more relevant in the sense that one of the cardinal principles for any president is to be able to grow and mature in office. And Kennedy demonstrated that quality. I feel like suddenly, we’re in an environment right now where that issue has become tantamount, and we’re all hoping that our latest president will also understand the need to grow and develop and evolve in the White House, to understand the need for empathy and conscience and moral courage.

MJ: Speaking of our current president, the FBI has been in the news a lot. Can you talk a little bit more about the troubling role of Edgar Hoover in this story?

SL: Hoover was an amazingly powerful man at the time. And he was a genuine racist who wanted to destroy King in any way he could. Once the [Kennedy] administration was in power, he also tried to influence and disrupt the relationship between [King and Kennedy]. He tried to pollute the relationship with the White House and with the Kennedy’s on that basis. And it was just another difficult hurdle that got in the way of a very difficult situation in trying to bring progress to civil rights.

MJ: What do you think the biggest takeaway from this book should be?

SL: The people who we think of as icons are really just like us. And like us, they all are trying to grow and improve and to be better people. So you have to look very closely at the actions and the development of people to see how that progresses. I think it truly happened with John Kennedy, and it was certainly happening with Martin Luther King ever since he became leader of the Montgomery Bus Boycott in the ’50s. By King’s example, Kennedy was pulled along as well. He was able to find it in himself to grow and mature and really change the course of American life—as much as he could in his short time in the White House—despite the great hurdles that lay ahead. The two of them together were on path of personal evolution for the betterment of the country.