Illustration by Mother Jones

All eyes on Capitol Hill on Thursday morning are on the testimony of Bill Browder, a longtime investor in Russia who spearheaded the passage of the Magnitsky Act, a 2012 law that has suddenly emerged at the center of the Trump-Russia scandal. According to Donald Trump Jr., Kremlin-linked lawyer Natalia Veselnitskaya complained about the law during their controversial June 2016 meeting at Trump Tower, to the apparent frustration of Trump Jr., who had been expecting a Russian emissary bearing incriminating information on Hillary Clinton. The law, sanctioning certain Russian officials, including members of Vladimir Putin’s inner circle, has been a major thorn in the side of the Kremlin, which has lobbied aggressively to repeal the measure. On Thursday, Browder, a hedge fund mogul who was banned from Russia in 2005, will speak at a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on enforcement of the Foreign Agents Registration Act, which requires people lobbying on behalf of foreign countries to disclose their activities. Browder will discuss how Veselnitskaya and several other political operatives lobbied to repeal the Magnitsky Act without registering as foreign agents, a possible violation of the law. Here’s what you need to know about the Magnitsky Act.

Who is Magnitsky?

The law is named after Sergei Magnitsky, a Russian lawyer representing Browder who died in a Russian prison under suspicious circumstances after uncovering a massive Kremlin-linked tax fraud scheme. The 37-year-old Magnitsky was in prison awaiting trial for 11 months at the time of his death.

What’s the story behind his death?

In June 2007, Russian authorities raided the Moscow office of Hermitage Capital Management, a London-based hedge fund run by Browder that had many investments in Russian companies. The authorities claimed to be investigating unpaid taxes by the firm. At the time, Magnitsky was working for Moscow law firm Firestone Duncan, which counted Hermitage as a client. Browder asked Magnitsky to investigate the reasons for the raid.

That request led Magnitsky to uncover a massive, Kremlin-linked tax fraud scheme involving 23 companies and hundreds of millions of dollars. In short, corrupt law enforcement and tax officials used documents seized in the office raid to draw up fake charters transferring ownership of Hermitage companies to a known criminal. Unbeknownst to Browder or Hermitage, officials then filed three lawsuits against those fake companies for breaching contracts (which were themselves falsified). Judges in the three suits awarded damages totaling exactly $230 million, meaning that Hermitage’s balance sheet no longer showed a profit. This meant the thieves could apply for a rebate on the taxes originally paid by Hermitage. The application for the $230 million refund—the largest in Russia’s history—was filed on Christmas Eve 2007 and approved the same day.

Browder and Magnitsky reported Magnitsky’s findings to Russian authorities, filing multiple criminal complaints. Magnitsky testified against the police officers who raided Hermitage’s offices. A couple of weeks later, he was arrested in Moscow, charged with tax evasion, and jailed. He was pressured to give evidence against Hermitage in exchange for his freedom. When he refused, he was kept in jail for 11 months before his death.

A 2011 investigation found that Magnitsky was beaten by eight guards and then denied medical attention as an ambulance stood outside the prison for more than an hour. Charges against one of the prison’s doctors were eventually dropped, while the head doctor was acquitted. In 2012 and 2013, Magnitsky was posthumously charged (for a second time) with and convicted of tax evasion—the first posthumous prosecution in Russia’s history.

After Magnitsky’s death, Browder became a vocal advocate against Russian corruption and traveled to Washington to tell Magnitsky’s story to Sens. John McCain (R-Ariz.) and Benjamin Cardin (D-Md.), who eventually introduced the Magnitsky Act.

What does the Magnitsky Act do?

The original law sanctioned 18 Russian officials and businessmen thought to be involved in Magnitsky’s death. In 2016, the law expanded sanctions to include 44 Russian citizens, many of whom are high-ranking government officials. The law was framed as an effort by the United States to call out human rights abuses by powerful Russians.

“It is the sense of Congress that the United States should continue to strongly support, and provide assistance to, the efforts of the Russian people to establish a vibrant democratic political system that respects individual liberties and human rights,” states the text of the law.

What’s the connection between the Magnitsky Act and Putin?

The original 18 people on the Magnitsky list were, for the most part, relatively minor players in the Magnitsky affair, though several top Interior Ministry officials who had led the Magnitsky investigation were included. But the list has been expanded in recent years to include top government officials and aides close to Putin. In January, the Treasury Department added former KGB agents Andrei Lugovoi and Dmitri Kovtun to the list. Both Kovtun and Lugovoi, a current member of Russian parliament, are suspected by British authorities in the 2006 poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko, a former Russian intelligence agent turned Putin critic. A close Putin aide and one of Russia’s top federal security officials, Aleksandr Bastrykin, was also added to the list.

The tax fraud that Magnitsky uncovered has recently been linked to top Russian officials, including Putin himself. The Panama Papers, the millions of leaked financial documents published last year that detailed the offshore banking operations of hundreds of politicians and businessmen across the globe, revealed that some of the money from the tax scam Magnitsky uncovered was linked to renowned Russia cellist Sergei Roldugin. Through Roldugin, that money is also possibly connected to Putin. The Panama Papers revealed that Roldugin, a close childhood friend of Putin, was part of an intricate network of Putin associates who moved $2 billion through offshore companies that all linked back to Bank Rossiya, a bank that is often dubbed “Putin’s wallet” in Russia because so many Putin allies are shareholders. The papers also revealed that Roldugin may be a conduit for Putin himself, helping hide the president’s mysterious fortune.

What’s been the Kremlin’s response?

Two weeks after President Barack Obama signed the Magnitsky Act, Putin retaliated by blocking adoptions of Russian children by US citizens. Between 1999 and 2012, American parents had adopted 46,113 Russian children, according to the State Department.

Since Putin’s move, many Russians advocating for repeal of the Magnitsky Act have described their goal as resolving the adoption impasse. Adoption has become a euphemism, a benign shorthand for attempts to convince the United States to repeal the Magnitsky Act.

“Adoption is a code,” Browder told Mother Jones recently. “When Putin mentions adoptions, it’s basically a hostage situation, where Putin is a terrorist who has taken his own children hostage and wants to negotiate their release and try to free up a ban on him and his government.”

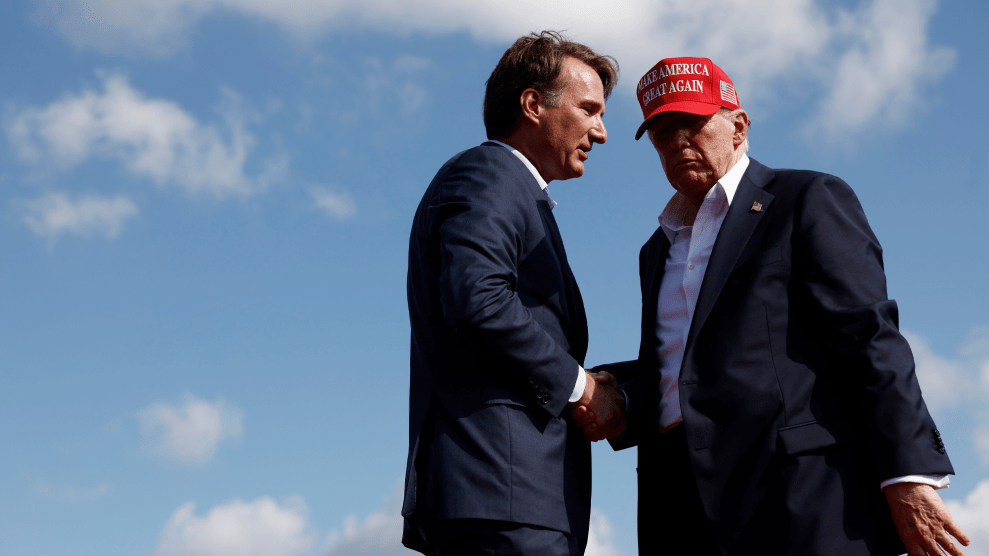

In this context, Veselnitskaya, the Russian lawyer tied to Putin allies, brought up adoptions during a June 2016 meeting with Trump Jr., President Donald Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner, and then-campaign chair Paul Manafort. Trump Jr. originally claimed the parties in the meeting “mostly talked about adoptions,” though he was forced later to admit he took the meeting hoping to receive damaging information on Clinton supplied by the Russian government. Veselnitskaya has denied that she was acting on behalf of the Russian government to collude with the Trump campaign, saying that she simply discussed the Magnitsky Act and adoption.

Putin himself seems to have used a similar rhetorical approach in a conversation with President Trump, not initially disclosed by the White House, at the G-20 Summit earlier this month. Trump described that meeting in an interview with the New York Times. It was unclear from his description if he fully understood the tie between adoptions and sanctions.

“It was very interesting,” Trump said. “We talked about adoption.”

He added, “I always found that interesting. Because, you know, he ended that years ago. And I actually talked about Russian adoption with him, which is interesting because it was a part of the conversation that Don [Jr.] had in that meeting.”

What would repealing the Magnitsky Act really mean?

Repealing the Magnitsky Act appears to be a priority for Putin and his allies because it hinders the ability of the officials on the list, many of whom have become rich while working in government, from entering the United States or using its banking system. The reach of the law is even broader because many foreign banks will not do business with individuals barred from banking in the United States. Repeal of the act would free those officials, and others who may be added to the list, to travel and stash money outside Russia.

Matthew Rojansky, who studies Russia as director of the Kennan Institute at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington, says the Kremlin views the law as an effort at regime change, due to Browder’s prominent role in advocating for it. Browder has said he is seeking Putin’s ouster.

But the law is a relatively small piece of a broad sanctions regime imposed on Russia by the United States and the European Union. The collective restrictions are widely credited, in combination with falling oil prices, with damaging Russia’s economy. The sanctions include asset freezes for specific Russian individuals and entities and restrictions on engaging in financial transactions with Russian firms in certain industries. They also include restrictions on US exports, services, and technology for specific Russian oil exploration and production projects and bans on US exports of certain military items to Russia. Russia wants all of the sanctions repealed.

Where does the Magnitsky Act stand now?

Behind lobbying by Browder and continued international concern about Putin’s human rights record, the reach of the act continues to expand. The last additions to the list of sanctioned individuals came in early January, and the Global Magnitsky Act, signed by Obama in 2016, targets any foreign citizen “responsible for extrajudicial killings, torture, or other gross violations of internationally recognized human rights committed against individuals in any foreign country.” Britain has a Magnitsky Act similar to the US law, and Canada is close to approving its own version of the law.

The scandal involving potential Trump campaign coordination with the Russian government during the 2016 campaign has left the Trump administration weakened and, it appears, unable to pursue Trump’s goal of achieving a grand bargain with Russia that includes the repeal of sanctions. The House on Tuesday voted 419-3 to approve a bill blocking the White House from weakening sanctions on Russia without congressional approval. The Senate is expected to easily approve the measure, sending it to Trump, who has wavered on whether he’ll sign it. If he does not, legislators appear to have ample votes to override his veto.

The Kremlin also appears to have abandoned hope of quick repeal under Trump. “Russia has very low expectations for relations with Washington now,” says Rojanksy. “The overwhelming focus is on Putin’s March 2018 reelection, for which the narrative of conflict with the USA and the West may actually help deliver more popular support.”

Image credits:Background: iStockphoto/Getty; Veselnitskaya: Yury Martyanov/Kommersant Photo/AP; Kushner: Bill Clark/Congressional Quarterly/Newscom/ZUMA; Putin: Metzel Mikhail/TASS/ZUMA; Don Jr: Richard Drew/AP