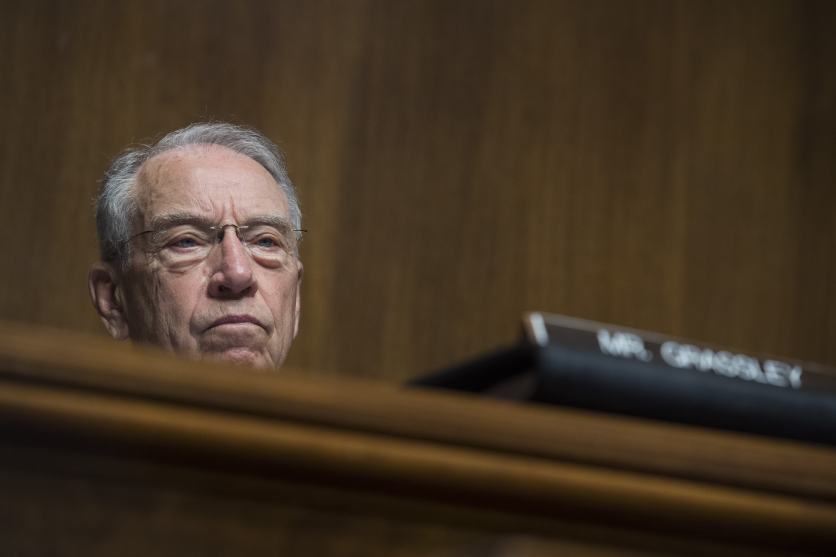

Sen. Charles Grassley (R-Iowa) oversees a June 28, 2017 judiciary committee hearing.Tom Williams/CQ/Roll Call via ZUMA Press

At a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing last week on Christopher Wray’s nomination to head the FBI, Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) quickly brought up President Donald Trump’s firing of former FBI Director James Comey. But the committee chairman didn’t fault Trump for Comey’s dismissal. Rather, Grassley defended Trump’s right to let him go. “There are no restrictions on the ability of any president to fire any director,” he said in his opening statement.

Grassley’s comment was significant because he heads what could wind up being the most consequential of the congressional investigations related to the Trump-Russia scandal: a probe of Trump’s firing of Comey and collusion between the Trump camp and Russia. The inquiry presumably will examine whether the president obstructed justice by axing the official leading the FBI’s investigation of interactions between the Trump camp and Russia and its related probe of Michael Flynn, Trump’s former national security adviser. The House and Senate intelligence committees are examining various aspects of the Trump-Russia controversy, and the FBI’s investigation is now proceeding under the leadership of Special Counsel Robert Mueller, who may also be examining Trump’s dumping of Comey.

But the Judiciary Committee, unlike these other outfits, operates mostly in public, and, more important, it can actively pursue the case of Comey’s firing—and Trump’s possible obstruction of justice—whether or not that episode involved any violations of the law.

The intensity and extent of the committee’s investigation of the Comey firing and other aspects of the Russia scandal depend on Grassley. And so far it looks like the 83-year-old Iowan is more interested in developing a counter-narrative to the Trump-Russia storyline by conducting a series of alternative investigations into tangential subjects. These inquiries seem designed to minimize the culpability of Trump and his aides and to deflect attention from the core issues of the controversy.

Grassley has sent a stream of letters to government agencies and private parties demanding information that is barely or loosely related to the Comey dismissal or Trump-Russia contacts. The letters suggest wrongdoing by those investigating Trump or imply equivalence between the actions of the Trump gang and the Obama crew. Put together, they offer a rough conservative narrative of government officials and others colluding and conspiring to take down Trump. At the least, Grassley’s missives appear aimed at undermining the credibility of agencies or people who have uncovered information on Trump.

Meanwhile, Grassley is reluctantly moving ahead on the main issues. That’s due in part to careful coaxing by Democrats on the Judiciary Committee. The committee’s ranking member, Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.), and other Democrats on the panel know they need Grassley on board for the committee to pursue a thorough investigation of the Comey firing and other Trump-Russia matters. Aware that Grassley resents criticism and revels in a nonpartisan image, they have mostly avoided accusing him of covering for Trump. The Democrats have also more or less accepted his alternative inquiries as the price of doing business and winning Grassley’s cooperation in the collusion and obstruction probes.

Feinstein tells Mother Jones that this strategy of nonconfrontation led to a deal, ratified last Tuesday in an exchange of memos between Democratic and Republican committee staffers, which ensures the committee will investigate alleged obstruction and collusion by Trump and his aides.

There is “agreement to look into issues related to Russian interference in the election and possible obstruction of justice,” Feinstein spokesman Tom Mentzer wrote in an email. Mentzer, though, declined to elaborate on specifics of the arrangement, which judiciary aides say replaces a less formal working agreement that had lacked clarity on what Grassley had agreed to investigate. Grassley’s office did not respond to requests for comment.

After the deal was reached, Grassley announced he would call former Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort to appear before the committee. He also agreed to Feinstein’s request that the committee ask Donald Trump Jr. to testify publicly before the panel regarding his June 2016 meeting with a Russian lawyer and an email exchange showing top Trump aides agreed to cooperate with what seemed to be a secret operation mounted by the Putin regime to disseminate negative information on Hillary Clinton to help Trump.

But while he moves ahead on those fronts, Grassley is also pushing his parallel probes and maintaining an idiosyncratic and at times truculent investigative approach.

Grassley has sent at least five letters this year to the Justice Department and the FBI asserting that Andrew McCabe, the FBI’s acting director, should have recused himself from the bureau’s probe into Trump campaign contacts with Russia because his wife received campaign contributions from the political action committee of Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe, a Clinton ally, during her unsuccessful 2015 Virginia state Senate bid. Grassley has cited reporting by the conservative news site Circa to assert McCabe should have also have recused himself from the bureau’s investigation of Flynn because Flynn wrote a letter supporting an FBI agent who had alleged she faced retaliation after filing a sex discrimination complaint in 2012.

Grassley said at the Wray nomination hearing last week that McCabe “was named in a sex discrimination case.” That’s a stretch. The report cited in Grassley’s letter says McCabe knew of an investigation into the FBI agent that she claimed amounted to retaliation—not that McCabe was personally accused of discrimination. Without presenting evidence, Grassley also called McCabe a “potential” suspect behind leaks of information on Flynn, a charge that McCabe has denied.

Grassley has tried to link McCabe and another entity he has portrayed as suspicious: Fusion GPS, the Washington, DC, firm that retained former British intelligence officer Christopher Steele to produce memos detailing allegations of secret ties between the Kremlin and Trump. Grassley has issued a series of committee letters demanding the firm hand over information on its clients and details of Steele’s work arrangement, including whether the FBI once planned to pay him for providing intelligence to the bureau.

Grassley has suggested that McCabe employed Steele as part of some anti-Trump effort. “The American people should know if the FBI’s second-in-command relied on Democrat-funded opposition research to justify an investigation of the Republican presidential campaign,” Grassley wrote in multiple letters. The letters, which include footnotes, do not document any contacts between Steele and McCabe.

But Grassley’s questions were picked up by conservative media outlets dismissive of the Russia scandal. “Chuck Grassley Asks If the FBI Helped Create Trump-Russia Allegations,” RedState.com said in a March 29 headline.

Grassley similarly helped fuel conservative talking points with a July 11 letter asking the State and Homeland Security departments how Natalia Veselnitskaya, the Russian lawyer who met with Trump Jr. and others in Trump Tower, had entered the United States after she was previously denied a visa. The query led to errant reports that the Justice Department had okayed an exemption for Veselnitkskaya, including a Drudge Report banner: “Obama DOJ Let the Russian In.” (The Homeland Security Department says the State Department issued her a visitor’s visa in 2016.) Other pro-Trump sites incorrectly claimed former Attorney General Loretta Lynch personally approved of the exemption, a claim President Trump parroted during a press conference in Paris on Thursday. “Somebody said that her visa or her passport to come into the country was approved by Attorney General Lynch,” Trump said.

Grassley is also not done with Clinton’s emails. He wrote to Secretary of State Rex Tillerson on March 30 asking if the department had concluded that Clinton’s email management was careless and whether it had launched a review into her “mishandling of classified information.”

Even as he pursues these disparate targets, Grassley has not sought to compel Attorney General Jeff Sessions to testify before his committee to explain Sessions’ false claim—made under oath at his confirmation hearing—that he had no contacts with Russian officials during the 2016 campaign. Nor has Grassley pressed Sessions, his former committee colleague, to explain how he squares his recusal from the Russia probe, which resulted from Sessions’ undisclosed meetings with Russian Ambassador Sergey Kislyak, with his role in Comey’s firing.

Democrats, no surprise, grouse that these Grassley moves are overly partisan. “It’s a mistake,” says Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) a former Judiciary chairman. “The committee is more and more controlled by politics.”

A part-time pig farmer, Grassley, the first chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee without a law degree, won a reputation for independence after joining the Senate in 1981. He drew notice for pressing Republican and Democratic administrations to curb spending and protect whistleblowers. He developed an experienced team of investigators that earned a reputation as an effective, free-ranging oversight force that ran probes on a variety of issues, from federal contracting to drug pricing.

Democrats who have worked with Grassley say his nonpartisan bonafides began to decline in 2009, when he acceded to heavy pressure from GOP leaders and conservative activists and dropped out of bipartisan negotiations with Democrats regarding President Barack Obama’s Affordable Care Act. Grassley ended up endorsing the false claim that Obamacare would create “death panels,” recalls Jim Manley, a onetime spokesman for former Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid and late Sen. Ted Kennedy. “He made his bed with the right and he’s been playing that game ever since,” Manley says.

Still, Grassley is no Devin Nunes (R-Calif.), the hapless House Intelligence Committee chairman who was forced to recuse himself from the panel’s Russia probe after a ham-handed effort to bolster Trump’s false charge that the Obama administration had wiretapped him. Nor is Grassley taking the approach of House Judiciary Chairman Bob Goodlatte (R-Va.), who has refused to even question the Trump administration on Comey’s firing or Sessions’ conduct.

Committee Democrats appear intent on playing to Grassley’s self-image as a fair and balanced chairman, ignoring his conspiratorial focus on events involving Fusion GPS and McCabe. Feinstein and Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I.), the top Democrat on the crime and terrorism subcommittee, even signed onto Grassley letters regarding former Attorney General Loretta Lynch’s actions in connection to the bureau’s investigation of the Clinton email controversy.

Democrats remain cautious as they work to nudge Grassley forward. Feinstein is quick to praise his forthrightness in their dealings. But when asked if his investigative zeal is hampered by a desire to avoid damage to the Republican president, she tersely says, “I think that’s right.” But she quickly adds, “I really like him, because he’s very clear. Things are either bad or good. He’s very direct and honest with me.”

Still, it is anyone’s guess just where Grassley is headed. Feinstein says she’s not sure how he will navigate the obstruction and collusion probe and the various tangents he is pursuing: “I don’t know what’s going on there.”