American soldier with his siblings before leaving for Vietnam. 1965. Courtesy Crocker Family/PBS

Novelist Robert Stone once likened the Vietnam War to a piece of shrapnel “embedded in our definition of who we are.” Who better to extract that shrapnel than Ken Burns, America’s preeminent documentary filmmaker? Ever since his definitive 1990 series, The Civil War, attracted a record 40 million viewers to PBS, Burns has been tackling historical topics ranging from jazz and the national parks to World War II, often in collaboration with director Lynn Novick. Ten years in the making, The Vietnam War, Burns and Novick’s 10-part journey into the most divisive of our 20th-century conflicts, premieres September 17 on PBS. (Read Klay’s interview with Novick at the bottom of this post.)

The series, which relies on the latest historical accounts, scores of participants, and a wealth of archival materials, gives voice to Vietnamese combatants and civilians in addition to the usual American experts, policymakers, veterans, and protesters. The result is a work of dramatic sweep and shocking intimacy—interspersing, for example, a US pilot’s frank description of bombing the Ho Chi Minh trail with the recollections of a Vietnamese woman who evaded a fiery death, or contrasting the last recorded words of a young draftee with snippets of private presidential conversations. The soundtrack includes classic songs of the era, plus new recordings by Yo-Yo Ma’s Silk Road Ensemble and Nine Inch Nails’ Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross—whose menacing theme music underscores the mayhem. As a veteran of the Iraq War who has written about the experiences of returning soldiers, I jumped at the chance to speak with Burns about his most formidable project to date.

Phil Klay: You’ve covered two wars already. Why this one?

South Vietnamese soldier comforts severely wounded comrade. Near Saigon. August 5, 1963.

Horst Faas/AP/PBS

Ken Burns: A good deal of the problems we have today had their seeds planted in the divisions it would produce. I grew up in the ’60s; I was eligible for the draft. My father was against the war, so I was against the war, but I paid attention. I watched the body count—I would be so happy [when] there were fewer [dead] Americans. I thought I knew a lot about it. And so I went in with the kind of arrogance that people with superficial knowledge always have. Lynn and I have spent 10 years shedding our feeble preconceptions. It was a daily humiliation.

PK: I was struck by what journalist Neil Sheehan told you: “It always galls me when I read or hear about the World War II generation as the greatest generation; these kids were just as gallant and courageous as anybody who fought in World War II.”

KB: I think what Neil was saying is that we don’t want to sentimentalize war. World War II is smothered in sentimentality and nostalgia. What’s interesting about Vietnam is that sentimentality is just not there, so you’re given kind of a clean access to it in one way. It’s also a war that represents a failure for the United States. Many people came back feeling like they never wanted to talk about it again. And so we developed a national amnesia.

PK: The war also came at a time when racial tensions in the United States were coming to a head—for instance, the way the draft functioned.

KB: African Americans saw the military as a way out of poverty—a job and steady pay. But as the civil rights movement reached a fever pitch, there was a disproportionate number of African Americans serving in combat roles and therefore being wounded and killed. The military, to their credit, did try to address this. But the larger thing is that Vietnam represents a kind of microcosm of America in the ’60s. One needs to go no further than Muhammad Ali: His saying “no Viet Cong ever called me ‘nigger'” is an important part of the story. And the way African Americans within units were segregated and made to feel inferior makes combat a very interesting flashpoint for racial issues. As one black soldier says, “They don’t care if you’re from Roxbury or South Boston; they’re shooting at you.”

Marines carrying their wounded during firefight near the DMZ. 1966.

Larry Burrows/Getty/PBS

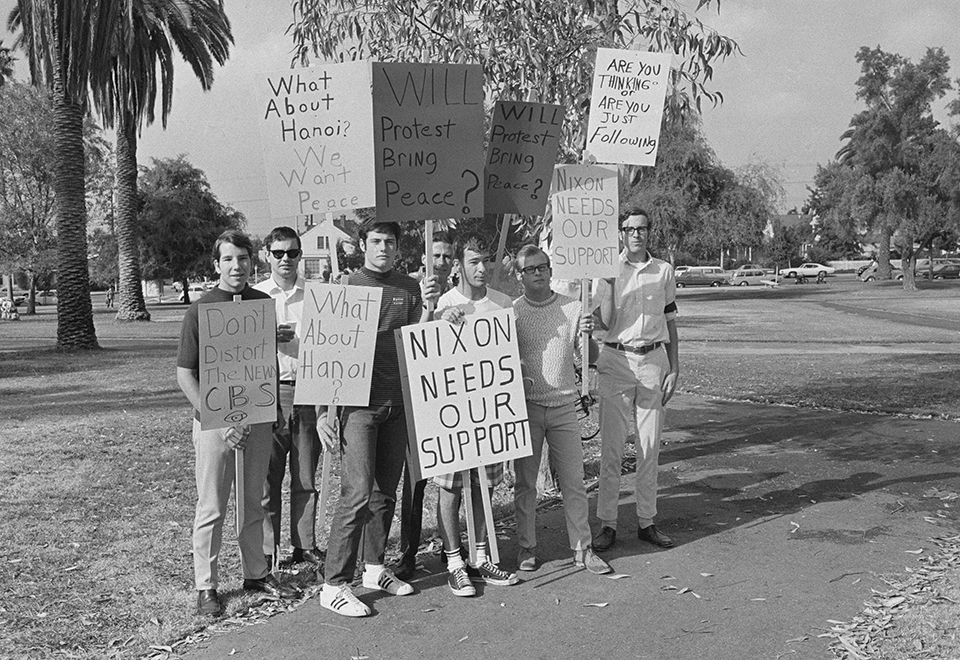

College students gather in support of President Richard Nixon. California, October 15, 1969.

WF/AP/PBS

PK: Were your Vietnamese participants concerned about how they would be portrayed?

KB: Of course—in the exact same fashion as the Americans. But after a few questions, they realized what we were about. You see them beginning to cop to stuff; the massacre of civilians after [the Tet Offensive battle of] Hue has never been acknowledged by the Vietnamese government, and we’ve got two of their soldiers describing it as an atrocity.

In The Best We Could Do, graphic novelist Thi Bui traces her family’s displacement from Vietnam in the 1970s. “It was me creating my own lexicon of images of Vietnamese people that were different from each other,” Bui says, “more wholly human than I’d seen before.”

PK: The Vietnamese American author Viet Thanh Nguyen talks about how every war is fought twice, once in fact and then—

KB: —in memory.

PK: Right. So how did you set out to retell a story that’s so often reduced to one about white college-aged men and their families grappling with going to war or not going—or coming home, or protesting—when the reality is so much broader?

KB: Thank you, Phil, for being the first person who has asked that. One way is to avail ourselves of the recent scholarship and begin to craft a narrative that is accurate to the real events of that war. Then populate the illustration of that war with enough variety of human experiences, American and Vietnamese, that it permits you to realize that memory is not just fragile, sometimes fraudulent, manipulated, and self-serving—but also accurate. You begin to realize that more than one truth can coexist.

KB: There’s nobody sitting there like a villain in a B movie, saying, “Oh, good, let’s go ruin this country and sully the name of the United States.” There are jerks and idiots at various points, but most of them are acting in good faith. This was something that was begun in secrecy and ended 30 years later in failure. That was a word we spent literally a year arguing over. It wasn’t a defeat; nobody took over the United States. It was not surrender. We failed.

PK: Your narrator opens by saying the war “was begun in good faith by decent people.” How do you square that with the duplicity depicted later in the documentary?

South Vietnamese soldier threatens a Viet Cong suspect. 1962.

Larry Burrows/Getty/PBS

PK: Larry Heinemann once said he wrote novels about Vietnam because that’s more polite than a simple “fuck you.” Was hiring Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross for the soundtrack your version of a polite fuck-you?

KB: That does a disservice to their artistry. We needed music that fit the period and the mood. Trent and Atticus are able to create music that is jarring and dissonant and anxiety-producing and at the same time resolves melodically and emotionally. Then we went to Yo-Yo Ma and the Silk Road Ensemble and said, “Here are some lullabies and folk tunes that everybody in Vietnam, North and South, would recognize.” The Vietnamese have said, “How did you know ‘Wounded Soldier,’ or this lullaby?” We had gotten into their inner hearts. Then, perhaps as importantly, we have 120 pieces from the greatest artists of that period, whether it’s Merle Haggard or the Beatles or Led Zeppelin or Otis Redding.

Viet Cong guerilla carries a wounded comrade, near the Cambodian border.

Courtesy Doug Niven/PBS

Newly released POWs rejoice on a C-141 plane during Operation Homecoming, 1973.

Courtesy National Archives/PBS

PK: Vietnam was carried out under five presidents. Iraq and Afghanistan are on their third. Did this series make you more hopeful about America’s ability to wrap up these conflicts—or less?

KB: Our job is just to tell the story, not to put up big neon signs saying, “Hey, isn’t this kind of like the present?” But we know historical narratives cannot help but be informed by our own fears and desires. The tactics the Viet Cong and also the North Vietnamese Army employed, as well as the Taliban and Al Qaeda and now ISIS, suggest an infinite war—and that’s why you hope that lessons of Vietnam can be distilled. Mark Twain is supposed to have said, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes.” We have spent our lives listening to the rhymes. Now history makes me an optimist. When people say, “This is the worst time ever!” I go, “Uh-huh.”

PK: So, how are you going to tell my war?

KB: I’m going to wait until 25, maybe 30 years out, and then we’ll see how it can be synthesized into something that might be coherent, but more imporatant, helpful. I really hope somebody will walk up to me one day and say, “This saved my life.” Or maybe just—let’s not be melodramatic—”I finally was able to communicate to my grandson what I had done and what I had seen and what I had felt, and it was okay to do that.”

North Vietnamese Army soldiers on the Ho Chi Minh Trail. 1969.

Le Minh Truong/Doug Niven / PBS

North Vietnamese Army officer leads an attack on South Vietnamese forces. Laos 1971.

Doug Niven / PBS

Below is a condensed version of Klay’s conversation with The Vietnam War co-director Lynn Novick.

Phil Klay: When you were coming into this project, I imagine you had a very different relationship with the Vietnam War than Ken did. He came of age at the war’s peak. You were born in 1962. How did the war affect you and your family at the time?

Lynn Novick: The war was ongoing for my entire childhood. I remember feeling like “It’s just never going to end,” it was a perpetual war. I don’t have any family members that were directly affected by it. My parents were too old, and they were too young to be in World War II, they slipped in between. I didn’t pay that much attention, to be honest, as a teenager, until the Hollywood movies started coming out in the late ’70s. They certainly imprinted me with some ideas about what the war might have been like. At the same time they were very melodramatic.

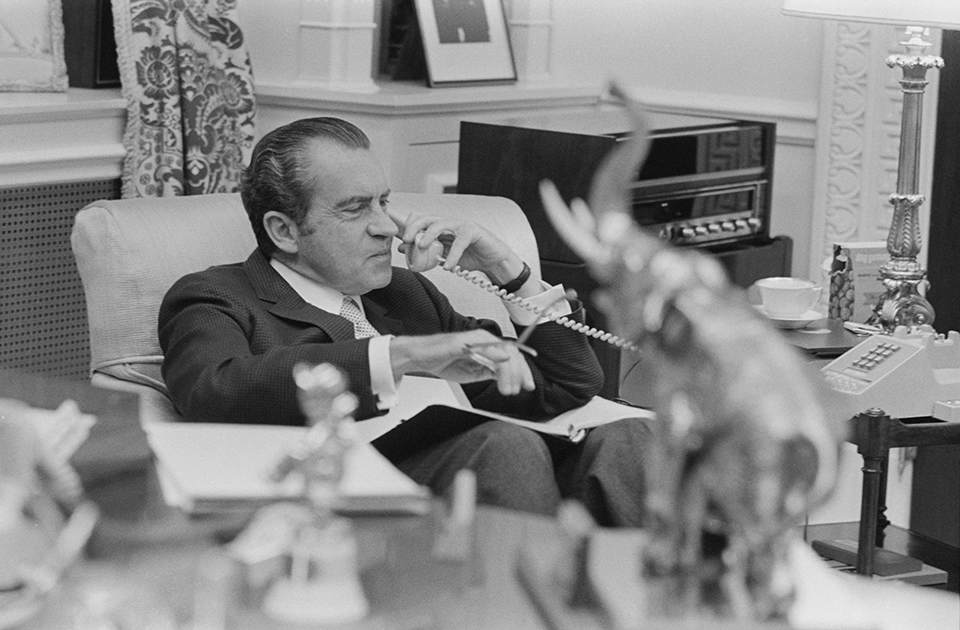

President Richard Nixon. November 11, 1971

Courtesy Richard Nixon Presidential Library / PBS

Antiwar demonstrators tried flower power on MPs blocking the Pentagon Building in Arlington, VA on October 26, 1967.

Bernie Boston / The Washington Post via Getty Images

PK: Your primary memory of the war was shaped by Hollywood.

LN: Well, not completely. That was my first visual experience of it I would say. As a kid, we didn’t have the TV on in the evening to watch the news. Yeah, the Hollywood movies and some fiction. Then, I started to become extremely interested and I read everything I could get my hands on from the time I was in college until we made the film. I remember the Stanley Karnow series coming out pretty soon after I graduated from college and being really blown away by it. That opened up a lot of questions in my mind that I certainly couldn’t answer.

PK: What would you say are the biggest fallacies about the Vietnam War that fictional movies have perpetuated?

LN: One blind spot in all the Hollywood movies that I remember is that the Vietnamese, if depicted at all, are completely one dimensional. I can’t think of a Hollywood film of the time that we’re discussing that really gives a dimensional representation of anything to do with what the Vietnamese were going through on both sides.

American soldiers display captured enemy flag. January 19, 1967.

Bettmann / Getty/PBS

PK: Some of the interviews with Vietnamese citizens and former soldiers in your series are just remarkable. What was it like convincing them to get on board with the project?

LN: It was really the same process in Vietnam as it was here—I wouldn’t differentiate that much between people’s reluctance or enthusiasm about doing this. A lot of is just connecting with someone and doing your homework, knowing a lot about them and their experience and whatever the environment that they were living in that you’re interesting in talking about. The people that we talked to in Vietnam were not reluctant. I guess that’s the best way to say it, or they wouldn’t have talked to us. They seemed extremely open to the idea. The only reason we were surprised was because we had no idea what to expect. We were surprised to find how open people were to talk about such a painful subject: just the scale of tragedy there, how many people were killed, how small of a country it is, how everybody was affected, the real horrors of the war. If I’d gone through something like that, I’m not sure I’d be able to talk about it.

A close-up of a young soldier in camouflage gear, North Vietnam.

Felix Greene / Contemporary Films, London/PBS

PK: I know certainly for a lot of the veterans that I know, a persistent bitterness has been America’s unwillingness to grant a sufficient number of visas for Iraqi and Afghan families. What are the lessons you drew from the stories of Vietnamese refugees who fled the war and its aftermath?

LN: To go back to the fall of Saigon, I felt it’s not the same bitterness that you and your colleagues feel about what has happened recently, but there was a sense that we abandoned our ally and we abandoned our people and left them at the mercy of the North Vietnamese. That is absolutely true. We let a pretty small number of people get out out right before the fall of Saigon compared to the numbers of people that probably wanted to leave. Then, we really weren’t welcoming people with open arms exactly. There was no kind of concerted effort to really take responsibility for the fact that we had hired people, we had promised them things. That all being said, there are over a million and a half Vietnamese-Americans living in the US today. They are extremely patriotic and loyal and just devoted Americans, that first generation. They often come from military families. There are people who got out of Vietnam who are grateful to be here for sure, but we also left behind a lot of people. We paid a heavy price.

PK: How do we achieve reconciliation?

LN: Wow, that is the $64,000 question. I don’t know. I’m optimistic that enough time has passed and that people can just reset and take a new look at this and have a different kind of conversation. We’ve seen it happen. I think there’s something extraordinarily powerful about the process of having to hear the stories of people you don’t agree with. It seems to open people up to hear each other and all I can say is we’ve seen it happen again and again in the conversations after screenings. These are informal focus groups of people who are bitterly opposed on many levels. After watching the entire film, they are willing to say “Well, maybe I didn’t understand as much where you were coming from and maybe I thought I was being patriotic, but at least I understand that you have a valid point of view and I underestimated you.”