Mother Jones Illustration; MagicVectorCreation/Getty; RawPixel/Getty

From the window of his university office in Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium, philosophy professor Philippe Van Parijs—considered by many to be Europe’s most prominent advocate for the idea that the state should provide a regular income to every citizen—can see the mailbox where he sent off invitations to the first “basic income” conference more than 30 years ago. “I’m quite amazed by the seed we threw on the ground now,” he says.

After decades of obscurity, the idea is suddenly in fashion. Politicians around the world are interested and a handful of governments, such as Finland and the Canadian province of Ontario, are planning or considering basic-income pilot projects.

But the idea of basic income has been around for more than 200 years, rising on waves of political and economic turmoil only to disappear in calmer times. Here are some of the highlights of its long, turbulent history:

1797: Thomas Paine proposes taxing landowners to provide a £10 annual stipend for people over 50 and a one-time £15 payment at 21 years of age.

1848: Belgian Joseph Charlier writes the first fully fledged proposal for basic income. It is virtually unknown until two academics stumble upon it 150 years later.

1918: After World War I, English Quakers call for a weekly “state bonus” for all citizens—a proposal ultimately rejected by the Labour Party.

1934: Amid the Great Depression, Louisiana Sen. Huey Long proposes confiscating wealth from the rich to provide guaranteed income for all families. The “Share Our Wealth” movement is cut short by Long’s assassination in 1935. That year, President Franklin D. Roosevelt creates Aid to Families With Dependent Children—the beginnings of “welfare.”

President Roosevelt, 1940

Wikimedia Commons

1940s: Conservative economists Milton Friedman and George Stigler propose a “negative income tax” (NIT): low-income households would receive government payments, and as earnings increased, so would the tax burden. Friedman believed an NIT would address poverty without adding to the state bureaucracy he reviled.

1962-63: Amid the Great Migration of blacks to the North, critic Dwight MacDonald argues for guaranteed income in an influential New Yorker article. Friedman presses for an NIT in Capitalism and Freedom, and liberal economist Robert Theobald floats a “Basic Economic Security Plan.”

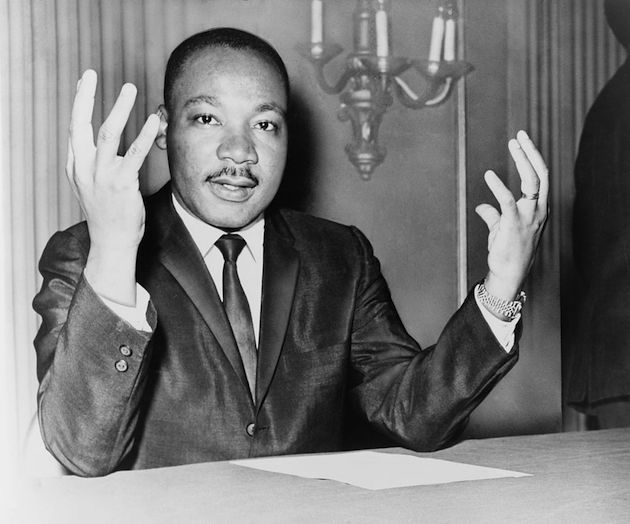

1966: President Lyndon Johnson’s economic advisers say an NIT “would be the most direct approach to reducing poverty.” By 1968, a surprising cast of characters, including Martin Luther King Jr. and CEOs, support the idea. Some 1,000 economists sign a statement advocating a “national system of income guarantees and supplements.”

The Reverend Martin Luther King in New York

Wikimedia Commons

1969: Richard Nixon repudiated guaranteed income on the campaign trail, but once in office, he is persuaded that it might be the best solution to the “welfare mess.” In a televised address in August, he presents a Family Assistance Plan, insisting it is “not a guaranteed income” due to work requirements. But families headed by both working and unemployed adults are eligible, erasing a historical line between the “deserving” and “undeserving” poor. Nixon’s bill stalls in the Senate Finance Committee. Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan tells Nixon that for Southern committee members, “it would very likely mean the end of those political dynasties built on poverty and racial division.”

1974: A tiny Canadian town provides residents an annual income of $15,000 for a family of four. The data is forgotten until 1,800 dusty boxes are found in a Winnipeg warehouse 40 years later.

1976: As the Trans-Alaska Pipeline nears completion, Alaskans approve a measure to pay dividends to all residents. Commencing in 1982, and paying an average of $1,150 a year to eligible residents ever since, the state oil fund is the first basic-income system in the United States.

Trans Alaska Crude Oil Pipeline in September 2016

Kim Mincer / Zuma

1978: US government NIT trials involving 4,800 families in two cities find a small reduction in “willingness” to work but a large increase of divorce in two cohorts. The divorce finding is later disputed, but the damage is done; Moynihan renounces guaranteed income. But by then, Nixon has pushed through Supplementary Security Income (for the old and disabled) and the Earned Income Tax Credit (an NIT for the poor).

1997: Mexico launches a program of conditional cash transfer to poor households. Brazil and Colombia follow suit. While CCTs come with requirements, they assume people will spend grants wisely. CCTs spread rapidly across Latin America and parts of Asia and Africa. Tens of millions of people worldwide now receive aid through CCTs funded by governments, aid organizations, and nonprofits.

2013: Basic-income experiments begin in rural India, involving more than 6,000 individuals.

2016: Switzerland becomes the first country to vote on, and reject, a national basic income. Opponents argued that it would undermine the Swiss economy. But for advocates, the mere fact of the referendum is remarkable. Meanwhile, as Silicon Valley bigwigs like Elon Musk make ever scarier pronouncements about the threat of AI, startup incubator Y Combinator announces a pilot project to distribute about $1,500 a month to 100 families in Oakland, California. And US-based nonprofit GiveDirectly plans a 12-year trial involving thousands of Kenyans.

2017: Pilot projects are initiated in Finland, the Netherlands, and three cities in Ontario, Canada, where low-income residents will be paid $14,000 a year whether they work or not. It’s time to be “bold,” says Ontario’s premier. And in September, Hillary Clinton reveals she had considered an “Alaska for America” basic-income proposal, funded by carbon and financial transaction taxes, but “couldn’t make the numbers work.”

Hillary Clinton’s What Happened book signing in New York

Erik Pendzich/Rex Shutterstock / Zuma

2017: Stockton, California, announces that in order to offset the economic inequalities brought on by the tech boom, it will begin a municipal pilot program known as SEED, or the Stockton Economic-Empowerment Demonstration. Some city residents may receive as much as $500 a month—not enough for anyone to subsist on exactly, but enough to ease some financial burden.