Union members, students, and activists march at a protest in Philadelphia in 2011. Matt Rourke/AP

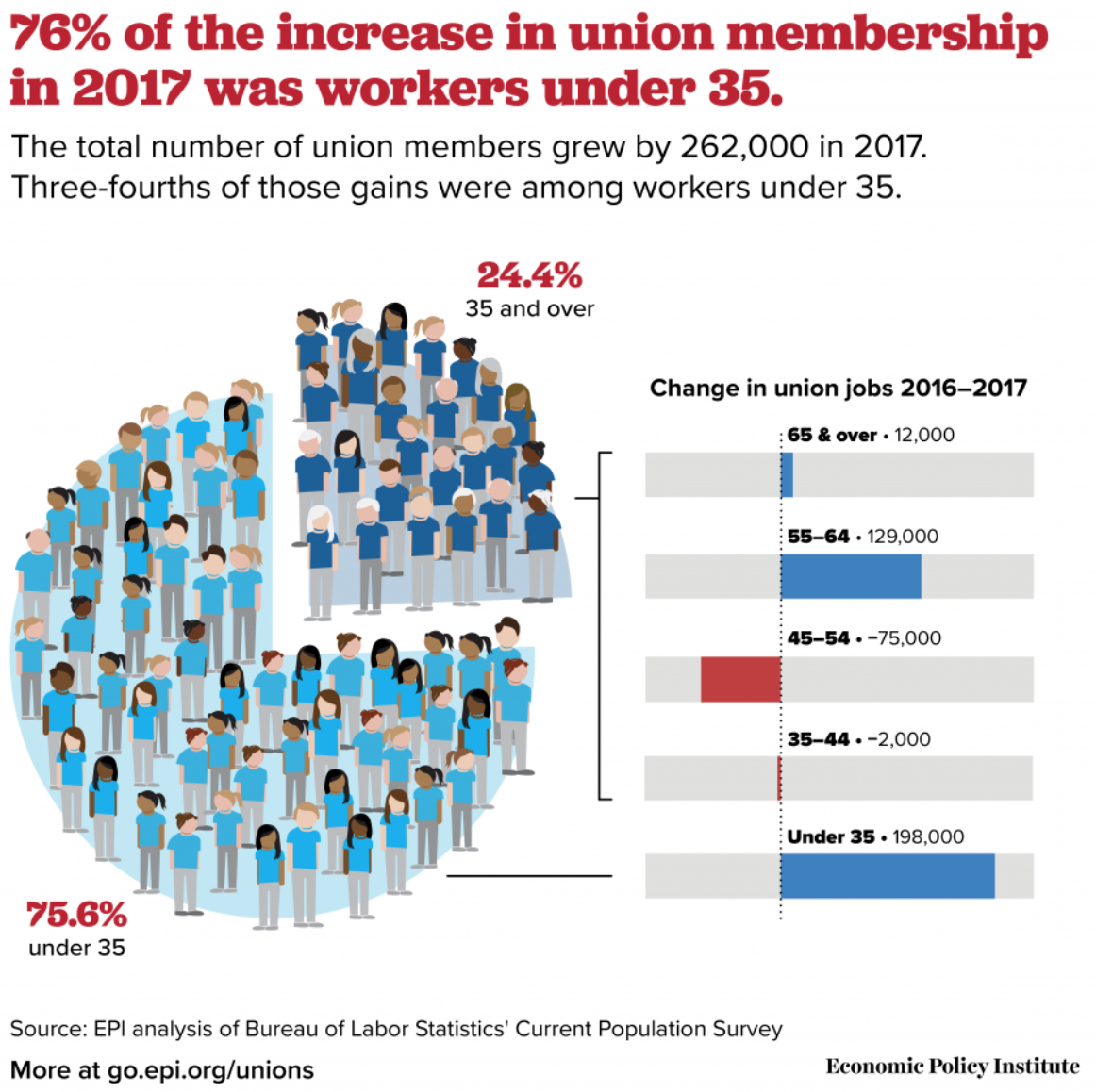

Add one more item to the list of retro things young Americans are rediscovering: unions. According to the Economic Policy Institute, a liberal think tank, 76 percent of new union members in 2017 were younger than 35. That’s pretty significant, considering that workers 34 and under make up just 40 percent of the country’s total workforce. In short, young workers may be kicking off a trend that could strengthen a labor movement that’s been brought to its knees by decades of attacks from employers, corporations, and hostile lawmakers.

These numbers represent a significant break with recent history. Younger workers have always been less likely than older ones to be unionized. This is still the case—roughly 8 percent of workers under 34 are union members, compared with around 13 percent of workers 35 and older. Yet nearly 1 in 4 new jobs among younger workers in 2017 was a union job. Recent polling suggests that today’s young workers increasingly identify with organized labor. Last year, Pew Research found that 75 percent of 18- to 29-year-olds (including 55 percent of young Republicans) have favorable views of unions—a rate far higher than that of any other age group.

John Schmitt, the vice president of EPI, points to the difficult economic landscape facing young people and a growing sense of powerlessness as one obvious reason why unions are getting a bump. “It is possible that the imagination of young people has been sparked,” he says. More of them may be receptive to “the idea of being in a union in order to counterbalance the power of the people that they work for.”

While it’s difficult to know which sectors are driving the growth in younger union membership, Schmitt points to the industries that are experiencing the most overall growth in unionization, including the public sector, construction, information, and education.

The knock-on effects of this shift could be even more significant. As Michelle Chen points out in The Nation, if union membership among young workers continues to climb as they become a larger part of workforce, it could pump desperately needed lifeblood into organized labor, potentially reviving a movement that’s often been pronounced dead. As the chart below shows, when workers’ bargaining power peaked sometime in the 1950s, so too did middle-class families’ share of total income. And when union rates started to tumble in the 1980s, so did middle-income share.

The economic outlook is bleak for many young people, who have “lower incomes, higher debts, and virtually no wealth to speak of,” according to the People’s Policy Project, a progressive think tank. It’s against this backdrop that they’ve formed increasingly progressive views; in one survey, 18- to 29-year-olds gave socialism a slightly higher favorability rating than capitalism. Younger workers have turned to “unions to find some security that the free market alone, that labor market alone,” fails to provide, Schmitt says. “Unionization, from better wages to better benefits, provides a degree of economic security that we just don’t have in the US economy.”