On a chilly, damp evening two years ago, 35-year-old Gina DiStefano found herself going through the trash outside Hip Hop Fish and Chicken in Baltimore, looking for uneaten meat on the bones. She was used to being hungry—DiStefano had used heroin on and off since she was 18, living in the damp, rat-infested basements of abandoned buildings. She had big, bloodshot eyes, a heart-shaped face streaked with dirt, and arms riddled with bedbug bites. To feed her addiction, she prostituted on Wilkens Avenue on the city’s west side. One thing fed off the other: The tricks gave her money for drugs; the drugs numbed the pain and shame of the tricks. Sometimes, as men did things to her in beat-up cars or smoke-filled motel rooms, she would imagine herself as a mannequin, flexible and devoid of feeling. But on that winter night, digging through diners’ napkins and bones, she couldn’t ignore the nausea in her gut, the swelling life in her belly. For the fourth time, she was pregnant.

Of the estimated 5.4 million women who abused opioid painkillers or heroin in 2016, some 26,000 were pregnant. (Both numbers are likely gross underestimates.) These pregnancies, nearly 9 in 10 of which are unplanned, carry major risks for mother and fetus alike. A woman who injects heroin through her pregnancy is significantly more likely than a nonuser to deliver a preterm baby with serious long-term health problems. Those risks diminish markedly if the mom takes medications to treat the addiction, but even so, the babies are often born in withdrawal. The condition, called neonatal abstinence syndrome, is characterized by high-pitched screaming, trembling, feeding difficulties, and hyperactive reflexes. “It’s like a collicky baby times five,” says Dr. Stephen Patrick, a neonatologist at Vanderbilt University who studies drugs’ effects on newborns. The long-term consequences aren’t well understood but may include trouble paying attention, verbal impairments, and diminished IQ. Reported cases of neonatal abstinence syndrome quintupled from 2000 to 2012, corresponding with increases in maternal drug use.

Babies Born In Drug Withdrawal: 2003 vs. 2013

The risks are compounded by the fact that many of the women come from poverty, have burned bridges with family and friends, and lack basics such as housing, transportation, regular meals, and medical care. “You’re not eating a healthy diet because you don’t even have access to that—you’re not even thinking about food,” explains Hendrée Jones, an obstetrics professor at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill and the director of Horizons, a center for pregnant and parenting drug users. “Dehydration and poor nutrition can be associated with poor birth outcomes. It’s all of the life factors—of which prenatal opioid use is one.”

RELATED: Children of the Opioid Epidemic Are Flooding Foster Homes. America Is Turning a Blind Eye.

There are strikingly few places for the women to turn. The stigma around drug use during pregnancy is so strong that many addiction treatment centers refuse pregnant women, creating what experts call “care deserts.” Some treatment centers even threaten to call the police or child protective services. What’s more, the only treatment typically available to indigent drug users are so-called gas-and-go clinics where patients get the one addiction medication offered, submit a cursory drug test every week or so, see a counselor about once a month, and never meet with a doctor.

“I don’t think there’s anyone more stigmatized than a pregnant woman with a substance abuse disorder,” Patrick says. “It’s very common for people to say, ‘Why would you do this with your baby?’” For the addicted moms-to-be, shame is a near-constant companion. When we spoke for the first time in August, DiStefano, who talks in a speedy, affable tone, volunteered, “I despise myself—I really do. I want you to know that.”

In a way, President Donald Trump acknowledged the lack of options for pregnant drug users in his State of the Union address. Among his guests was an Albuquerque, New Mexico, police officer who adopted the child of a pregnant woman addicted to heroin. “She told him she did not know where to turn but badly wanted a safe home for her baby,” Trump said, promising to help drug users get treatment. Despite his rhetoric, Trump has so far done very little that experts think could make a dent in the drug crisis—and has actually pursued a number of policies that could make it worse. He’s repeatedly proposed cutting services that would help drug users and their children—programs such as Medicaid, the Administration for Children and Families, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program.

Unlike many in her position, DiStefano had a place to go. A sex worker had told her about the Center for Addiction and Pregnancy at Johns Hopkins, a hulking brick building on the outskirts of Baltimore. The center, known as CAP, is one of the few places in the country that offers pregnant drug users comprehensive support—addiction treatment, OB-GYN services, pregnancy and parenting classes, hot meals, and, critically, shelter—under one roof. “It’s like walking out of a nightmare into the best thing that you can dream at that point because you feel so unworthy,” DiStefano says. At any given time, there are about 50 women receiving treatment, some of whom stay in CAP’s 16-bed housing unit. The building’s interior is like a homey hospital, with linoleum floors and hospital beds in the shelter area, colorful murals in the pediatric waiting room, trays of hot food in the cafeteria, and inspirational quotes dotting the walls.

CAP opened in 1991, after doctors at Johns Hopkins noticed that pregnant drug users in the outpatient addiction program weren’t getting prenatal or obstetric care—even though there were plenty of qualified doctors on the renowned medical campus. “People with substance abuse disorders can’t manage fractionated care,” says Dr. Lauren Jansson, CAP’s founding pediatrician. “You can’t say, ‘Go to this hospital for a week; go here for pediatrics; come here for your medication every day.’ It just doesn’t happen.”

Within a few years, studies were showing that the program, funded almost wholly by Medicaid, was effective: Compared with those who weren’t getting drug treatment, the CAP moms were less likely to use drugs throughout their pregnancy, and their infants were born healthier, spending less time in the neonatal intensive care unit. And on top of it, CAP saved money—nearly $5,000 per mother-infant pair—because newborns spent less time in the neonatal ICU.

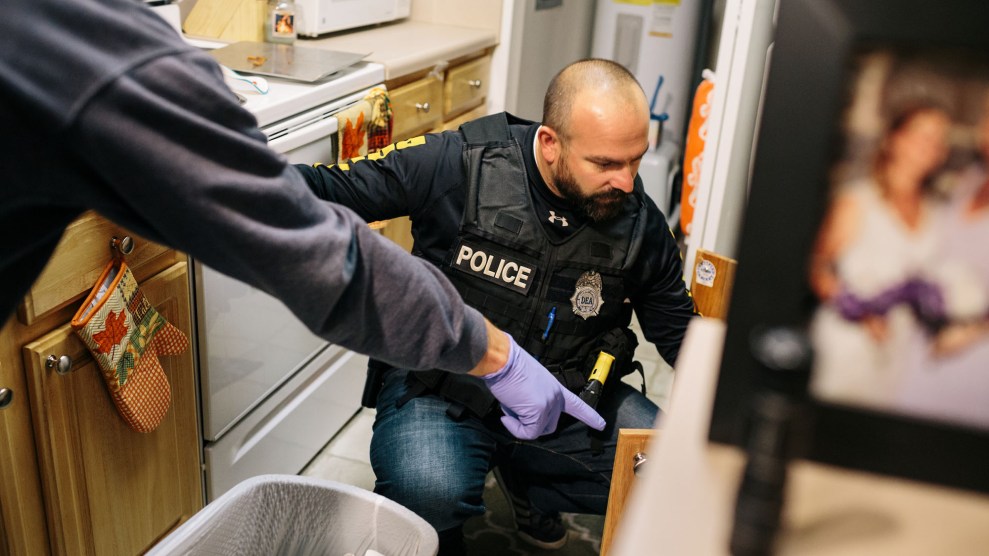

RELATED: Embedded with the suburban cops confronting the opioid epidemic

“The resources that we spend on moms to have good outcomes we get paid back tenfold with children with less developmental disabilities, better outcomes, and more contributions to society,” explains Dr. Neeraj Gandotra, CAP’s medical director. About 85 percent of pregnant women arrive testing positive for opioids—from pain pills to heroin to fentanyl. By the time they deliver, roughly 90 percent are free of illicit drugs.

Over time, the patient demographic has “flip-flopped completely,” says clinic supervisor Andrea Sweet. When CAP first started, most patients were impoverished black women who were addicted to cocaine; today, the typical patient is a white woman from a middle-class family who finds herself homeless, pregnant, and addicted to heroin or painkillers.

When a woman arrives at CAP, the first order of business is figuring out how to get her off illicit drugs—a process firmly framed as treating a disease that has taken over the brain, as opposed to a moral failing. “The reality is that when we have a headache we take an aspirin,” says Gandotra. “We don’t think twice about it. You take antibiotics when you have an infection. When there’s a treatment available, you should seek it.” Treatment for opioid addiction usually combines psychotherapy with medications such as methadone or buprenorphine, opioids that help satisfy cravings for more harmful drugs like heroin or fentanyl without getting the person high.

Effective treatment programs also tackle factors that drive drug use. Four out of five women arrive at CAP with a psychiatric diagnosis—usually depression. “One of the things that gets forgotten about is the amazing amount of trauma: childhood abuse, sexual, physical, and emotional abuse that gets carried into adulthood,” explains Jones, the Horizons director. “I’ve never met a woman who said, ‘When I grow up, I want to be a heroin injector.”

The drug use fuels a spiraling feedback loop: It may start as a reaction to trauma, but the lengths women go to get the mind-numbing powder can themselves be traumatic. “At CAP, mostly everyone that was there had prostituted at some time or had a sugar daddy—some old man,” DiStefano says. Paying for drugs with sex is hardly just an urban practice. “The drug-using world is very much a male-dominated world,” explains Jones, who sees the same behaviors among her suburban and rural patients. “What are you going to use to pay for your drugs? The only thing you have is your body.”

When a woman goes into labor at CAP, she is rushed in an ambulance across a parking lot to the hospital’s labor and delivery unit. There, nurses and doctors face a paradox of sorts: They want to treat the pain and often lean on alternatives to opioids, like epidurals. But sometimes—especially after a cesarean section—opioids are the only option. In the hospital, a nurse watches as the patient swallows the painkiller, but getting a bottle of oxycodone to take home presents an ever-present temptation for a user in recovery. As Sweet put it, “You don’t want the person to suffer, but at the same time, you hate the fact that they’re being given pills, which is a trigger.”

RELATED: A Brief, Blood-Boiling History of the Opioid Epidemic

Any newborn who’s been exposed to opioids—which is most CAP babies—is assessed every four hours for withdrawal symptoms for at least four days. While many hospitals immediately send drug-exposed babies to the NICU, CAP generally tries to keep the infants with their moms and encourages breastfeeding. That’s typical of the center’s measured approach, avoiding what some experts call “neonatal abstinence syndrome hysteria.” The knee-jerk rush to the NICU in many hospitals, while well intentioned, is shortsighted: Babies in withdrawal fare better in quiet, dim spaces with maternal contact rather than in a bright, beeping intensive-care setting. With a wave of opioid-exposed babies, says Jones, it’s critical to avoid the fearmongering that came with so-called crack babies. “We know from the ’80s and ’90s that there was a rush to judgement around prenatal exposure to cocaine, and it took another 20 years of research to show that there are effects, but it’s much more subtle than we had originally been told.”

After the baby is born, social workers check in with the mom and her counselor to see if she’s been actively using, if she’s been attending treatment, and ultimately if she’s fit to take the infant home. These conversations can be excruciating: Removing a child from his or her family, sometimes into an overrun foster care system, can be traumatic, yet so too is growing up with a drug-using parent. Complicating matters is the reality that, as therapists put it, relapse is part of recovery: Most users turn back to drug use multiple times before they stop altogether. “I can never say that I won’t ever relapse,” said Michelle, a 34-year-old CAP patient with warm eyes and a booming laugh. “I can say that I will do everything in my power to not relapse.”

Like DiStefano, Michelle was a prostitute for years, seeing as many as 20 men in a day before collapsing with exhaustion in bus stops or abandoned homes. The previous pregnancies had been a blur—she was once so high on heroin when her water broke that she thought she had peed herself. But her prior relapses have taught her to look for signs that she’s headed toward using again: She’ll stop cooking, stop calling her mom, stop taking her antidepressants. “My depression gets me every time,” she added.

At the time of my visit in August, Michelle was holding her fourth child, a one-month-old named Blessing, all big eyes and curly hair and pink ribbons. Michelle beamed. “It’s like—when she looks at me, and she holds my finger, it’s like she knows I’m mommy.”

Michelle and Blessing at CAP

Mark Helenowski / Mother Jones

DiStefano, too, has relapsed several times: Her latest trip to CAP was her third over four pregnancies. She did well with her first and second daughters before relapsing and losing them, to relatives and adoption, respectively. When the third daughter came along six years ago, the only places for DiStefano to turn were a bedbug-infested shelter or the home of a sugar daddy in his 70s, so she put her newborn up for adoption. “Please love her,” she begged as she handed the girl to her new parents. “Love her the way I love her. It’s just that I don’t have anything to give her.” During her latest pregnancy, in 2015, she arrived at CAP a gaunt shell of her old, outgoing self. “They didn’t even recognize me,” she remembers. When a staff member finally realized who she was talking to, “she threw her arms around me and hugged me. It’s all the love I had in the world at that point.”

DiStefano walks me through her pregnancies in a raspy, rapid-fire voice before pausing. “You probably think, ‘Wow, you had to come back three times—what’s wrong with you?” she says. “Sometimes it just takes a while. I had to keep hitting my head on the same walls.”

A number of studies have found that programs like CAP that pair addiction treatment with pregnancy, pediatric, or child care services lead to higher treatment retention and lower recidivism rates. Yet there are only a handful of programs in the country that bundle these services—programs like MATER in Philadelphia, Shields for Families in Los Angeles, and Horizons in Chapel Hill. That’s in part because it’s hard to convince potential funders that they’re a good investment in the short term, especially for a population that doesn’t have private insurance. CAP relies almost exclusively on Medicaid to fund the operation, which includes about $1,500 per woman per week for the medications, the facilities, the food, and the salaries of social workers, psychiatrists, pediatricians, and OB-GYN doctors.

Gina DiStefano and her daughter Emma

Courtesy of Gina DiStefano

Cuts to Medicaid would further exacerbate existing gaps in health care, says Jansson, the CAP pediatrician. Under hospital rules, Jansson can’t see patients without insurance, but in Maryland, health insurance is often canceled if a resident moves—a frequent occurrence for the demographic CAP serves. “Our mothers are often very transient, moving from shelter to shelter,” she adds. “For these children to lose insurance—or even if insurance is harder to get—it would decimate their ability to be immunized, let alone all the other things we need to do, right in the middle of an opioid epidemic.”

CAP’s patients are expected to return for daily parenting classes and appointments for the first few weeks or months after delivery. It is a challenging time for any new parent, and it’s particularly trying for a former drug user. The infants are often still feeling the withdrawal symptoms, which means they’re extra fussy. And home often is the same place the mom was living before, now with an oversensitive baby. “People are angry with them in the house,” says Sweet, the CAP supervisor. “There’s yelling. There’s drug use.”

And there are the stressors of any mother in poverty: the lack of daycare and sleep and money to pay for rent and heat and food and diapers and strollers. Mothers with drug felonies on their records have trouble getting into public housing or finding work. Those with jobs have to figure out how to pay for child care. “We’re asking them to be superhuman,” says Sweet.

It all adds up to a perfect storm for relapse. For Michelle, Blessing’s mom, it came in November, three months after we first met. She couldn’t pay her bills. She felt overwhelmed by caring for her four-year-old and four-month-old all by herself. She also had postpartum depression, particularly common among women with histories of drug use. “I could not stop crying,” Michelle recalls. “Tears were just falling for no reason.” So one day she did a line of coke, and then to come down from her high, she snorted heroin. Her fragile, blossoming life soon fell to pieces. Within a few days, she was bringing men home for sex while the kids were asleep. A few days later, children’s services came for them. A few days after that, she learned that she was, once again, pregnant.

The speed at which things go bad after that first hit of heroin can be jarring, even for Sweet. “Relapse is just rampant after people deliver,” she says. “It does feel like, ‘Oh my gosh, last week she’d been doing phenomenally for many months, and now, poof, she’s suddenly back, deep into drugs.”

Emma and her father

Courtesy of Gina DiStefano

But there are remarkable recoveries, too. DiStefano, who two years ago was eating out of the trash, transitioned from CAP to a treatment facility for recovering users and their kids, and eventually to an apartment, where she now lives with her boyfriend. He installs floors; her days are dominated by their two-year-old, who I’ll call Emma. They have a backyard where Emma plays and DiStefano grows lettuce and blueberries and herbs. When she takes Emma to the park, she watches the moms from wealthy neighborhoods—how they dress, how they discipline their kids—and tries to emulate them. At nights, she is working toward a degree in addiction counseling. As she talks about her life—the morning walks, afternoon trips to the grocery store, bedtime reading to Emma, who’s already saying her ABCs—she sounds in awe, as if she can’t quite believe it herself. “Why was I so blessed to get this perfectly beautiful girl?” she asks repeatedly. “I know that I don’t deserve her.”

Things are far from perfect. The apartment isn’t in a great part of town. Her boyfriend, a recovering heroin user, is on home detention. There’s an insidious, ever-present guilt that she’s not raising her older daughters, too. She feels behind on life—as if she were sucked into a black hole for more than a decade while her high school friends were building careers and families. And finally, there’s the fear that another relapse could come, and that the only thing standing between her present life and that of a homeless prostitute could be a line of heroin.

Perhaps what’s most different from DiStefano’s past periods of sobriety, she says, is that she has goals that seem increasingly realistic: She’ll move to a nicer home with Emma and her boyfriend, she’ll get her degree and start a practice counseling women who struggle with addiction. And when she does, she knows what she’ll tell them: “You have to get out of it long enough to let your life come into focus,” she says, sitting on her living-room sofa as Emma watches Barney. “It doesn’t happen at first and that’s okay. That’s what I want people to know.”