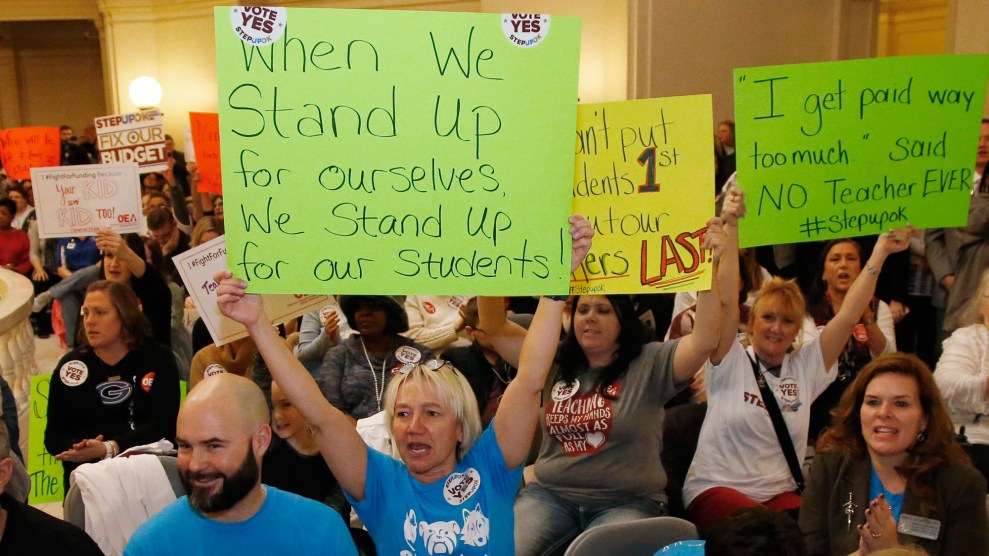

Edmond school counselor Wendy Joseph, left, cheers with other supporters of the teacher pay raise during a rally at the state Capitol in Oklahoma City in February.Sue Ogrocki/AP

If Oklahoma teachers walk out of classrooms in two weeks, Mickey Miller will not be among them—though he wishes he could be.

The economics teacher at Booker T. Washington High School in Tulsa is planning instead to pick up extra hours at his second job as a baggage handler at the nearby airport. With his first child on the way, Miller will continue to work the second job just as he had for the last five-and-a-half years.

“I would love to march with my fellow teachers to the Capitol. I want to support the cause and I definitely believe in it,” says Miller, who has taught in Oklahoma for 11 years. “Their voices will be heard, with or without me. I need to make money. I need the extra hours.”

Miller’s circumstances are, sadly, far from unusual. That’s why educators throughout Oklahoma, underpaid and frustrated by years of legislative cuts to public school funding, are already planning a walkout as a last resort if lawmakers fail to address funding concerns before the legislative session ends in May. Now, teachers are organizing on Facebook and preparing to walk out of schools on April 2 if their demands aren’t satisfied.

The Oklahoma Education Association, the state’s teachers union, has called for a $10,000 salary increase for teachers, $5,000 for educational support personnel, and $200 million toward public schools—more than $800 million in new funds over the next fiscal year. While state lawmakers decide how to move forward, the union is preparing its own proposal for how to pay for teacher raises and more school funding, though the specifics have yet to be released.

“Teachers are frustrated because the legislature hasn’t listened to them,” says OEA president Alicia Priest. “They are tired of asking, tired of begging, of not being listened to.”

Oklahoma educators are emboldened by the recent victory of their peers in West Virginia, whose prolonged strike in protest of meager salaries and rising health insurance costs forced schools to close for nine days, the longest in state history. Earlier this month, Gov. Jim Justice met their demands—he signed a five percent raise and created a commission to deal with insurance costs for all public employees across the state.

As a result of the worsening finances for Oklahoma’s public schools, 91 of the state’s 513 districts —roughly 20 percent—have switched to four-day school weeks, meaning students are left in school for, in many cases, an extra 45 minutes daily. Bus routes have been cut; once-cherished arts and language programs and athletic programs are gone. Some districts have eliminated AP classes and student support positions like librarians, counselors, and speech pathologists. Class sizes have ballooned in some districts, meaning teachers have less time to grade papers and give feedback. And as in West Virginia, Oklahoma educators are under strain from high health insurance costs.

Thousands respond to a teacher’s union survey supporting a walk out of the Legislature fails again to raise revenue and pass a teacher pay raise. The Oklahoma Education Association will announce its own plan Thursday. #okleg pic.twitter.com/QDqk0NTNz3

— Catherine Sweeney (@CathJSweeney) March 5, 2018

The average salary for an Oklahoma teacher is among the lowest in the nation at $45,245, according to the National Center for Education Statistics, even less than teachers in West Virginia were making when they decided to strike. More than a decade has passed since Oklahoma teachers were last given a raise. Now, many Oklahoma teachers like Miller have had to take up second jobs to make ends meet. Some have fled across the state and decamped to private and charter schools for better pay, others independently raise money to purchase school supplies for students.

“Oklahoma can’t afford to have teachers say they won’t come back,” Miller says. “No one wants to be a teacher in Oklahoma. They all left already. The pay is so low, and the conditions are so bad.”

Teresa Danks, a third-grade teacher and founder of the nonprofit Begging for Education in Oklahoma, told Mother Jones that she has experienced these challenges firsthand. In order to make ends meet, Danks has taken on after-school tutoring and teaching English online. Last year, she made headlines when she panhandled for money to purchase school supplies to stock classrooms. Now, she’s one of the many teachers calling for a walkout.

“It’s sad when your second job is paying you money for your first job,” she says.

As more teachers have relocated to states like Arkansas and Texas for better pay, Oklahoma has struggled with a statewide teacher shortage. Last fall, the Oklahoma State Department of Education found that in the first three months of the 2016-2017 school year, the agency approved 1,429 emergency certification application to allow schools to fill open positions with teachers who have not finished their certification requirements. That’s more than all the emergency applications approved during the 2015-2016 school year alone. Currently, nearly 2,000 emergency certified teachers work in Oklahoma.

What’s more, lawmakers’ ambitious plans to cut taxes for their constituents have backfired, putting a financial strain on schools and a slew of other social services.

Since 2008, Oklahoma lawmakers have made more cuts to public school funding than any other state in the country, cutting per-student spending by 28 percent, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, even as student enrollment was rising. In West Virginia, it was 11 percent. Republicans in the Oklahoma legislature have also slashed the state’s top income tax rate and reduced taxes for oil and gas production over the years.

Efforts to fix the state’s education funding have not fared well. In February, Gov. Mary Fallon, who once pushed to abolish the income tax rate altogether, urged lawmakers to pass a series of tax increases endorsed by business leaders that would raise teacher salaries by $5,000, a month after she promised to veto a budget that didn’t include a raise. That effort narrowly failed in the state House. Last week, Republican lawmakers devised a plan that would give teachers a $20,000 raise over six years. OEA’s Priest criticized the plan as a “political stunt that falls woefully short of the revenue needed to save our schools and keep teachers in Oklahoma classrooms.”

The last time Oklahoma teachers went on strike was in 1990. After thousands of teachers shut down schools for four days, affecting more than 300,000 students, Oklahoma lawmakers passed a bill that raised teacher salaries, raised taxes for funding, and limited class sizes. But decades later, funding for public schools languished, and the effort to keep class sizes small fizzled. After seeing West Virginia educators come out of a strike victorious, teachers in Oklahoma feel like they have a fresh shot at making a change.

“Seeing what happened in West Virginia gave us some hope, an outline of what to do and what not to do,” Miller says.

The momentum from the West Virginia wildcat strike appears to be catching on in other red states, as well. In Arizona, thousands of teachers wore red to protest low pay and understaffed schools, which, as in Oklahoma, has meant classrooms are helmed by under-qualified teachers. To address these concerns, the Arizona legislature increased teacher pay by 1 percent last year and plans to add another 1 percent this year. For perspective, that would be a $500 per year increase to the median salary of roughly $46,000. Some teachers plan to call in sick and protest at the state Capitol to pressure the legislature to raise teachers’ wages further.

And on March 7, hundreds of teachers in Kentucky rallied to oppose a bill in the state Senate that would cut billions of dollars in public worker benefits, which would also affect retired teachers, as a way to solve the state’s pension system problem. On Wednesday, at least 60 Kentucky schools closed as teachers protested looming cuts, just a week after Gov. Matt Bevin called teachers challenging the pension cuts “ignorant” and “selfish” during a radio interview. Earlier this week, as Puerto Rican lawmakers considered an education overhaul measure that would pave the way for charter schools and vouchers on the island, thousands of teachers marched to in San Juan in protest. (On Wednesday, the reform measure passed and awaits Gov. Ricard Rossello’s signature.) Earlier this year, Rossello released a fiscal plan that would close 300 schools on the island and cutting $300 million in school spending, putting teachers’ jobs at risk.

Oklahoma schools boards have been bracing for the possibility of a statewide strike. At a school board meeting in late February, Bartlesville superintendent Chuck McCauley unveiled a list of 30 districts that he says expressed interest in a “suspension of schools to support teachers,” which would affect 25 percent of the state’s 695,000 students in public school, according to the Tulsa World. Tulsa and Oklahoma City, the state’s two largest districts, passed resolutions that support the teachers’ efforts to “take any steps necessary to improve conditions for our teachers—including a districtwide suspension of classes.”

At least half of the state’s largest districts, which account for one-third of all students in Oklahoma, have come up with contingency plans in the event of a walkout. In Oklahoma City, meals will be bussed to students throughout the district, and the district is working with local organizations to coordinate child care services and meals. If students in Oklahoma City miss more than four instructional days, the days will either be added to the school year or school days will grow longer.

For now, all signs indicate that teachers will walk in nearly two weeks. Last week, some Oklahoma teachers left schools when the final bell rang as a way to “work the contract,” meaning, in Tulsa, for example, they didn’t work more than seven hours and 50 minutes in a school day and students’ work wouldn’t get graded. Still, during their spring break this week, some teachers have driven to Oklahoma’s Capitol to meet with lawmakers and lobby for a raise to avoid a walkout.

“The end goal is funding for public education. The end goal is not a walkout,” Priest says. “We’re in an education funding crisis and our legislature needs to put partisan politics aside, egos aside, and whatever has allowed us to get into this big hole and do what’s right for the kids of Oklahoma.”

Larry Cagle, an English teacher at Edison Preparatory School and one of the organizers on Facebook, spent his week visiting teachers in far-flung rural districts to discuss the walkout effort. At 54, Cagle says he brings in $1,900 a month and works in construction during the summer to pay the bills.

“We all felt that the time has come. We weren’t wrong. We were in the right place at the right time in the right moment of history,” he says.