When asylum seekers arrive in the United States they face a harsh reality. The ones who aren’t illegally turned away at the border are often sequestered, shackled, and transported to a detention facility that resembles prison.

Since the mid ’90s, the US has followed a policy of mandatory detention for most asylum seekers and deportation for people convicted of certain criminal acts, many of them nonviolent offenses. Once people make it across the border and are expedited to a nearby facility, they can be held indefinitely with limited access to communication and legal representation—a situation made even more dire since the Supreme Court late last month reversed a lower court ruling that guaranteed some detained immigrants have the right to a bond hearing within six months. They now have no such protections.

These policies have created an immense backlog in immigration courts; as of April 2017, there were 585,930 people waiting for a decision on their status, with an average wait time of 670 days. Currently 34,000 beds in private and public facilities have to be filled daily to justify the expense.

Photographer Ed Kashi and I were determined to bring former detainees out from the shadows so they could tell their stories firsthand. The resulting portraits feature people who have been detained between 1996 and the present. They are now all living in the US with asylum status, with the exception of Ravi Ragbir, who was recently re-detained and, his lawyers claim, illegally targeted for his outspoken views on immigration policies. The photographs depict former detainees who stand firmly resolute, even while their physical surroundings seem to be receding. They are here and not here, at home and adrift, uncertain of their place in the country. They inhabit the between-worlds where they struggle to reconcile the opportunity America affords them and the abuse they have suffered at her hands.

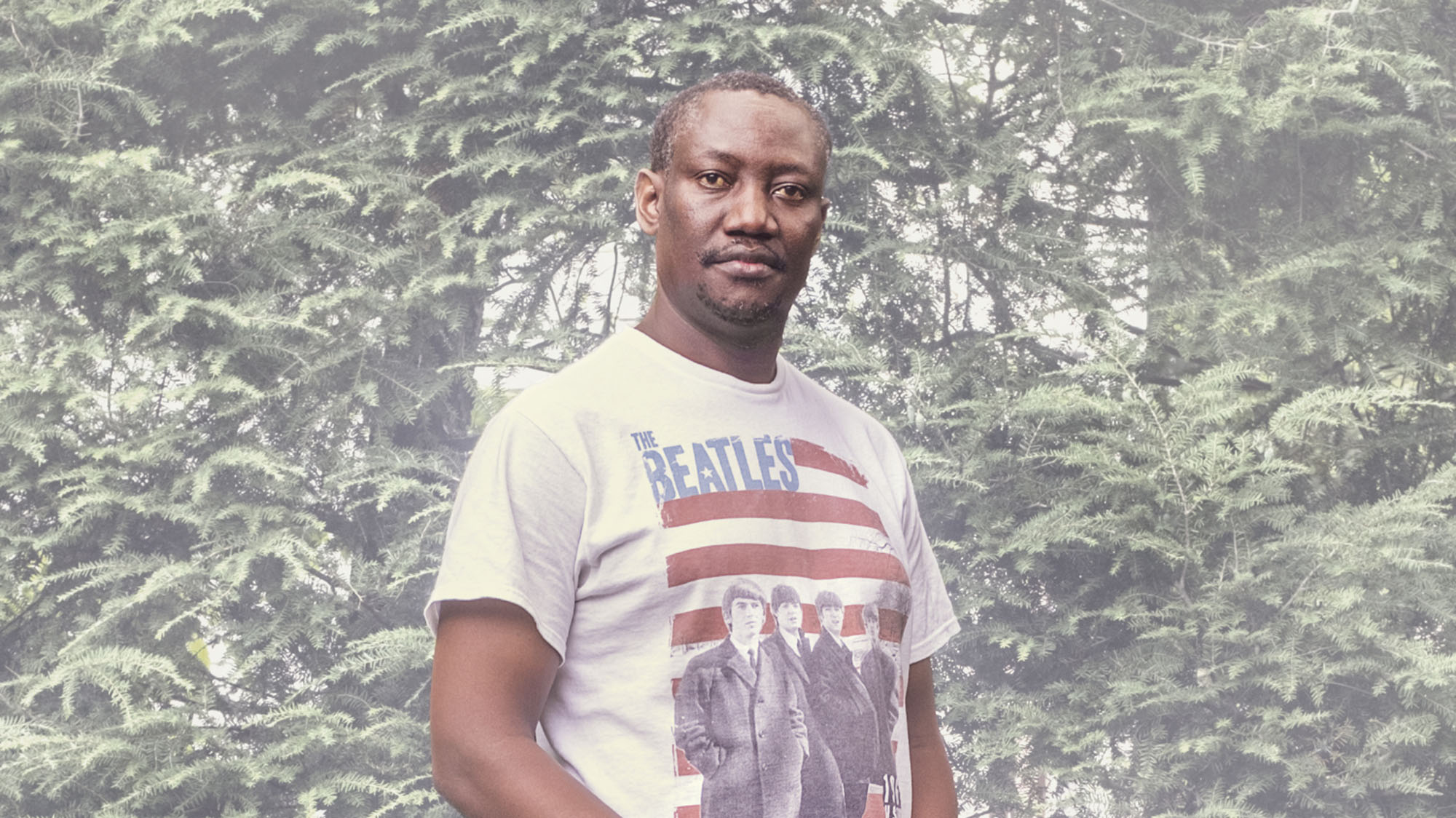

Abu Bakar, originally from Sierra Leone, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on August 12, 2017. He was a detainee for three years at Elizabeth Detention Center, Bucks County Prison, and Allentown prison, and was part of a lawsuit against the Esmor Corporation, a private company that ran the Elizabeth Detention Center at the time he was detained.

Ed Kashi/VII

Most of the detainees featured here were held at New Jersey’s Elizabeth Detention Center, which was one of the first privately run facilities. When it opened in 1994, it was managed by the Esmor Corporation and detainees there were routinely abused: physically, mentally, and emotionally. The people held there rioted in 1995 against the inhumane conditions and, eventually, sued. The resulting lawsuit marked the first case in which non-citizens were allowed to sue in US courts. Abu Bakar and Kou Cecile Jeffrey, pictured here, were two plaintiffs in the precedent-setting lawsuit. While the court ultimately ruled in favor of the detainees and Esmor lost its contract to operate the facility, the company itself didn’t disappear. Esmor re-incorporated as Correctional Services Corporation, and it currently operates juvenile offender facilities across the country, some of which have been accused of perpetrating numerous abuses and being responsible for several deaths.

Every person in this series describes detention situations in which serious health conditions were neglected, verbal and physical harassment was rampant, rotten food was served, and dismal wages were paid to detainees to help run the facilities. These men and women were isolated from their families, deprived of many basic human rights, and stuck in an indefinite state of limbo. Some version of this is the reality for nearly 400,000 people each year.

Kou Cecile Jeffrey, originally from Liberia, in Staten Island, New York, on October 5, 2017. 20 years ago, she was held in Elizabeth Detention Center and Bucks County Prison for three years.

Ed Kashi/VII

“Ahmed,” originally from Djibouti, in Jersey City, New Jersey, on August 9, 2017. Ahmed was a judo champion who was arrested and tortured in his home country after being accused of anti-government actions; his name has been changed and his identity obscured due to fear of retribution by the government. He was held in the Elizabeth Detention Center for five months and 22 days.

Ed Kashi/VII

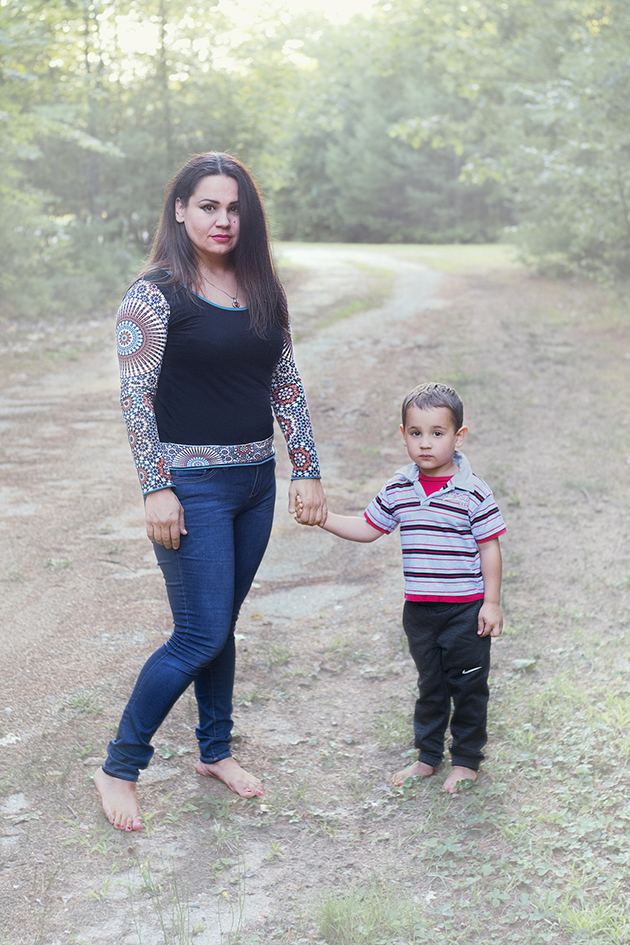

Juliet Horton, originally from Uzbekistan, with her four-year-old son Arthur in Oxford, Maine, on August 23, 2017. She was in immigrant detention at the Hudson County Jail and Hartford Correctional Center for two years and nine months.

Ed Kashi/VII

Chause Kugonza, originally from Uganda, in Glen Rock, New Jersey, on August 8, 2017. Kugonza was tortured in his home country for being a gay man, and when he sought asylum in the United States, he was held in the Elizabeth Detention Center for five months and seven days. He is now living in a volunteer’s house while he sorts out his asylum status.

Ed Kashi/VII

Juan Carlos Hoyos, originally from Colombia, in East Newark, New Jersey, on August 24, 2017. Hoyos fled his country to seek political asylum. He was detained at the Elizabeth Detention Center for six months.

Ed Kashi/VII

Ravi Ragbir, originally from Trinidad & Tobago, in New York, New York, on August 17, 2017. He was convicted of fraud and detained at Bergen County Jail and Perry County Jail for two years.

Ed Kashi/VII

Edafe Okporo, originally from Nigeria, in Jersey City, New Jersey, on August 13, 2017. He escaped persecution for being gay in his home country and was held at the Elizabeth Detention Center for six months.

Ed Kashi/VII