Pablo Martinez Monsivais/AP

A report released by the Education Department on Tuesday reveals that black students and students with disabilities are still suspended and arrested at much higher rates than their classmates, further complicating Education Secretary Betsy DeVos’ reconsideration of an Obama-era rule meant to curtail the disproportionate punishment of students of color.

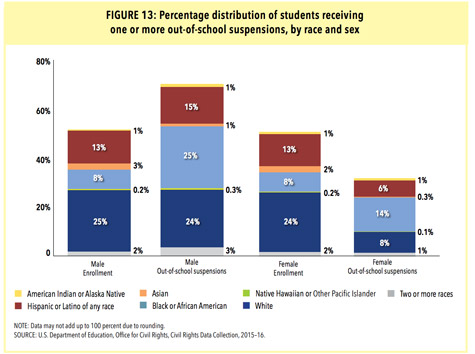

According to the Education Department, 2.7 million K-12 students were suspended at least once during the 2015-16 school year, the most recent year for which data is available. Black students make up 15 percent of students enrolled in schools across the country but accounted for 39 percent of those suspended out of school at least once. Black boys, who make up 8 percent of the student population, accounted for 25 percent of suspended students, while black girls (another 8 percent of students) accounted for 14 percent of those suspended.

Of the 120,700 students expelled from school in 2015-16, 33 percent were black. Black students were also overrepresented among those who were physically restrained (27 percent) and secluded in rooms in which they were prevented from leaving (23 percent).

What’s more, black students were more likely to get referred to law enforcement and arrested at school, a notable finding considering the Trump administration called for more cops in schools following the Parkland shooting. Black students account for 31 percent of all referrals to law enforcement, up 4 percentage points from the 2013-14 school year.

Students with disabilities, meanwhile, were subject to 26 percent of out-of-school suspensions, even though they made up 12 percent of students.

Suspensions can ultimately lead to a loss of instruction time that could overwhelmingly fall on students of color and those with disabilities. A report released last week by the UCLA Center for Civil Rights Remedies and Harvard Law School’s Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice found that black students with disabilities were more likely to be suspended and lost 77 more days of instruction, on average, than their white peers. In at least 28 states, the gap between disciplining black students with disabilities and white students worsened between 2013-14 and 2015-16.

Dan Losen, director of the Center for Civil Rights Remedies at UCLA, tweeted out several examples of what the newly released discipline data meant in several urban school districts:

New OCR data on Memphis show Black males lost 83,727 days of instruction due 2 out of school suspensions, yet only 43,216 Black males r enrolled. That =s 194 days lost for every 100 Black males! Every district reports days lost showing profound impact on ed opportunity .@losendan

— Dan Losen (@losendan) April 24, 2018

Ferguson MO schools Black males lost 9,905 days of instruction 2 suspension with only 4,695 enrolled =s 211 days per 100 enrolled + White mls lost 54 days per 100. 157 more days lost per 100 for Black mls @SarahDSparks @EricaLG OCR released data but this not mentioned. .@losendan

— Dan Losen (@losendan) April 24, 2018

OCR data out today, in Jefferson Cty Kentucky, Black males lost 115 days lost 2 out of school suspension per 100 enrolled which is 81 days per 100 more than the 34 days lost for white mls enrolled. A devastating racially disparate impact on educational opportunity. .@losendan

— Dan Losen (@losendan) April 24, 2018

On April 4, DeVos held closed-door listening sessions with educators and advocates on both sides of the Obama-era discipline rule. The guidance, issued in 2014, seeks to ensure that schools don’t disproportionately punish black and Latino students for wrongdoing and encourages schools to look at their own disciplinary policies. Members of a White House school safety commission, overseen by DeVos, is looking into repealing the guidance.

That same day, a report released by the Government Accountability Office found that black students, students with disabilities, and boys were far more likely to be disciplined than their classmates. The GAO report notes that “implicit bias” from teachers and staffers “may cause them to judge students’ behaviors differently based on the students’ race and sex.”

In December, the Education Department also proposed delaying another Obama-era guidance, known as the significant disproportionality rule, that’s meant to require states to look at whether schools are overidentifying students of color for special education or disciplining students of color at higher rates.

This article has been revised.