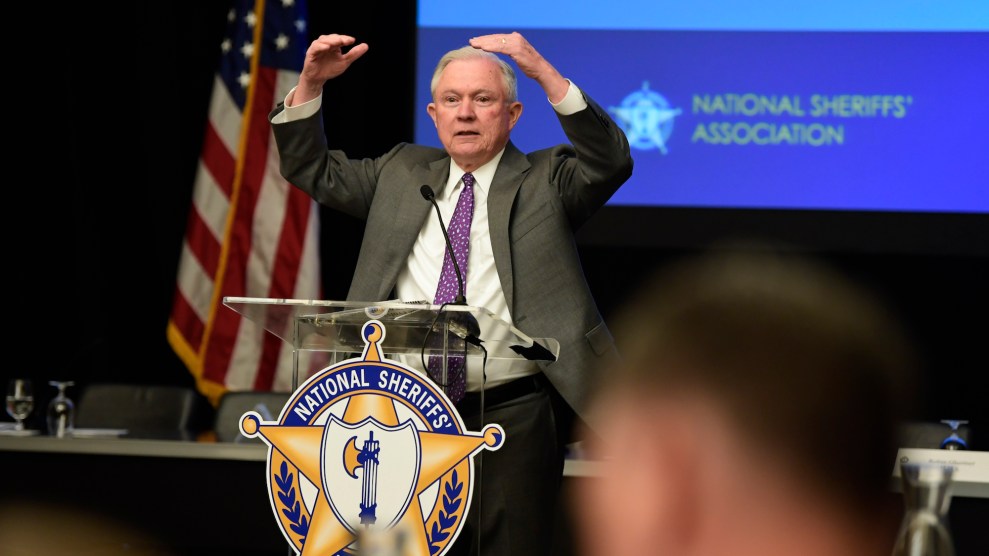

Susan Walsh/AP

Over the past 10 years, the backlog in America’s immigration courts has nearly quadrupled to roughly 700,000 cases. On Thursday, Attorney General Jeff Sessions issued a decision that could dramatically expand that backlog at a time when immigrants often wait years before judges decide whether they can remain in the United States.

Using his control over the immigration court system, which is part of the Justice Department, Sessions revoked immigration judges’ broad authority to close cases through a process known as administrative closure. This procedure does not provide permanent residency to immigrants, but it can allow them to live in the United States indefinitely. As a result of Sessions’ move, immigration judges will not be able to set aside low-priority cases, as they often did under under the Obama administration. They will also no longer be able to close cases in which the defendant is waiting to receive a visa, although Sessions’ move does make narrow exceptions. And they may soon be forced to reopen many of the roughly 350,000 cases that were administratively closed before the end of the 2017 fiscal year—further straining a court system that is already overwhelmed.

Sessions’ decision did not immediately reopen all of the closed cases and provided narrow grounds for when judges can still use administrative closure. It will now be up to the Department of Homeland Security to decide how many cases it will ask judges to “recalendar,” or reopen.

I interviewed San Francisco immigration judge Dana Marks about the dramatic impact the decision could have on immigration courts. Marks spoke on behalf of the National Association of Immigration Judges, where she served as president until last year.

Mother Jones: What is administrative closure?

Dana Marks: Administrative closure is a tool that immigration judges have used as a way to take a case off the active court docket and set it aside. Basically, it was out of the court’s calendaring system until one of the parties would make a motion to bring the case back to the active docket. One way to describe is it as a “docket management tool.”

MJ: How significant is this decision?

DM: The court backlog that we’ve been struggling with has been in the neighborhood of 700,000. You add another 300,000 to it. That’s extremely significant. Extremely significant. And although the Department of Justice has been trying hard to increase the size of the immigration judge corps, it has not been happening fast enough to impact the backlog. We’re struggling to keep up with new receipts, let alone have sufficient capacity to be able to significantly reduce the backlog of cases that we have.

MJ: How was administrative closure used during the Obama administration?

DM: There was a huge increase [in] use of administrative closure under the Obama administration, when it was used as a procedure tool to try to prioritize scarce resources. When the court dockets began to get more and more backlogged, Immigration and Customs Enforcement would agree [to use] prosecutorial discretion to close certain cases. Let’s say someone was encountered in a workplace investigation and they had no criminal background. Often in those years, if someone had a clean record and had been here a significant period of time, they could ask for administrative closure. And the Department of Homeland Security wouldn’t oppose it. Particularly [in] the last five or six years, it had just exponentially grown in usage. It was a conscious choice, but that’s also what I believe brought this to a head. All of a sudden the numbers of cases that were off the immigration court docket for whatever reason really mushroomed.

MJ: Is Sessions’ argument new?

DM: I’d say it’s a relatively new development. It had not been something that I had seen raised in my 40 years of practice in the field. It obviously has enough reasonable arguments on both sides that you get these kinds of analyses that come to completely opposite conclusions at the end.

MJ: How will this affect the existing backlog?

DM: The decision makes clear that either party will be able to move to recalendar. The impact on the court dockets is going to depend on whether DHS makes a decision to go through their files and file as many motions to recalendar as they physically can, or not. If the attorney general is correct [about the number of closed cases], then that puts us over a million cases on our immigration court dockets if those were all restored. Now I’m sure that they will not all be restored to the active docket. There may be some [types] of cases that will not be restored. But we have no way of knowing. That would not be within the control of the immigration courts.

MJ: Your organization has argued for making immigration courts independent of the Department of Justice. How does this decision relate to that position?

DM: The fact that the immigration courts are subject to decisions which are made presumably based on a political agenda is a strong reason why our association believes that the immigration court should be taken out of a political branch of government—that we should be made an independent court, which would mean that these kind of decisions could not happen. The judges would be in control of their docket, and we believe that is the procedurally correct way for these cases to be handled. And certainly, with the stakes for people in immigration court being so high, we believe that a traditional court system is a far better way to assure that people are treated fairly and that the actions taken are transparent. Our criticism is not partisan. It’s an observation about what we think is the proper legal structure, and then the decisions will fall where they may.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.