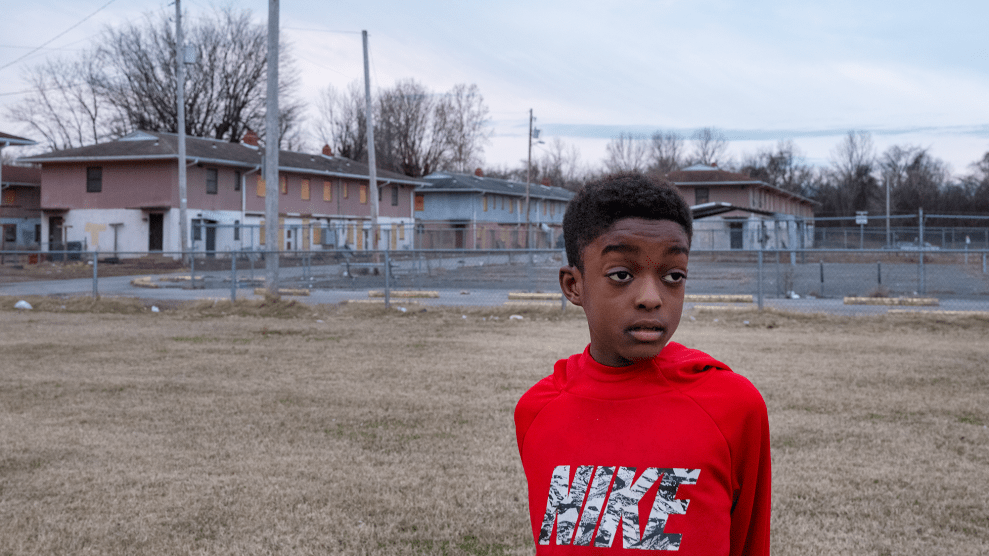

The McBride public housing project in Cairo, Illinois.Richard Sitler/The Southern Illinoisan via AP

In the current issue of the magazine I reported on the public housing crisis in Cairo, Illinois, where Ben Carson’s Department of Housing and Urban Development announced last year it was shutting down the city’s two largest housing projects and forcing the relocation of hundreds of residents. Residents were given until July 1, 2018, to find new housing, which in many cases, meant leaving the town or even the state. Carson’s decision made the town a national story, but the problem started much earlier.

HUD had known about serious problems at the Alexander County Housing Authority—grift, racial discrimination, and deteriorating living conditions—since at least 2010, yet was slow to address them for years as the situation worsened. (HUD finally put the housing authority under receivership in 2016.) Last year, HUD’s Office of Inspector General launched an investigation into the agency’s oversight of the housing authority, and this week it finally published its findings.

There’s no one big smoking gun. Rather, the OIG report is a story of a cautious and slow-moving bureaucracy that’s unable, or perhaps unwilling, to respond quickly when a crisis emerges.

One takeaway from the report is that the problems laid bare by the response to Cairo were not unique; they are endemic to the department as currently constituted. For instance, as I’d been told by several ex-HUD officials during the reporting of my piece, the investigation found that receivership is considered an action of last resort because the department simply doesn’t have the manpower, money, or expertise to routinely take over housing authorities for an indefinite period of time.

“The small pool of experienced receivers, inadequate guidance, and outdated training pose organizational risks that could negatively affect HUD’s oversight of PHAs [public housing authorities] over time,” the investigators wrote. “Without these elements, HUD may avoid taking PHAs into receivership when it is necessary and may oversee PHAs in receivership improperly or inadequately.”

The reluctance to step in, in this case, meant that HUD kept giving the housing authority more and more chances to fail.

The report offers an additional explanation for the reluctance to take over the troubled agency: “HUD officials added that the agency must consider the political repercussions from taking a PHA into receivership.” That’s a familiar explanation, and it speaks to a fundamental problem fair housing advocates have with the way HUD is structured—local politicians tend to view HUD as more of a bank than a necessary collaborator, and they don’t want the bank to close.

Cairo was no exception. In one email to HUD, an interim executive director (who took the job after the situation had begun to fall apart) complained that the county government’s sole wish was to “turn the money back on.” Following a contentious 2013 on-site meeting in Cairo that got the ball rolling, the city’s Democratic congressman wrote to HUD’s Chicago office on behalf of the housing authority, offering to mediate any problems. An internal memo cited the letter as proof that James Wilson, the authority’s longtime executive director and Cairo’s former mayor, was “politically connected.”

In the case of the Cairo, part of the delay also owed to the prospect of a legal challenge that might overturn a receivership order; in order to make sure its case was iron-clad, HUD had to make sure the housing authority really was failing. But time was a luxury that residents of public housing could ill afford. Their living conditions continued to deteriorate as Washington waited.

Given those impediments, the only way to really avoid the chaos that followed would have been to catch things early, but there was a problem there, too. Because of a faulty contractor-driven inspections process, the housing authority didn’t set off the tripwires it should have.

HUD’s policy is to wait until a housing authority has flunked inspections two years in a row before declaring it “troubled,” triggering a heightened level of oversight and bringing it a step closer to receivership. But one year after its first sub-standard inspection score, inspectors inexplicably—the report doesn’t actually explain how—showed a tremendous improvement at Elmwood and McBride, the two public housing complexes that HUD closed earlier this month. HUD then asked for a re-score, which ended up taking months. When the results came back, their 0-100 score of 82 had been reduced to 28—enough to finally label the housing authority “troubled” and begin the process that led to receivership.

The flawed inspection was an egregious error, and in the end, a costly one, that forced hundreds of Cairo residents continued to live in racially segregated apartments heated by gas stoves; amid peeling paint, rats, and roaches; for months, if not years, more than necessary. “The living conditions at ACHA posed an immediate threat to its residents,” the investigation concluded. Residents paid the price for HUD’s inaction.

You can read the full report below: