It was fitting that not long before the opening of her major retrospective at the San Francisco MoMA this summer, Susan Meiselas was back in Nicaragua, making photos. Her coverage of the Nicaraguan revolution 40 years ago helped launch her career; now, at the opening of her exhibition in mid-July, she lamented the current state of the Central American country, once again embroiled in a violent revolution to overthrow a repressive government. The script has flipped with Daniel Ortega, brought to power by the Sandinasta revolution that Meiselas covered, accused of a brutal crackdown on protesters.

Though that work is a cornerstone of her career as a photojournalist, Meiselas wanted to keep the Nicaragua part of her show from just being historical revolutionary porn, so she included a postcard of a recent photograph she made in Nicaragua. The image is of a young man spray painting “SOS NICARAGUA” on a concrete wall, reflecting early work Meiselas made of revolutionaries painting murals. The postcard is a small but important gesture indicating the continuation of history photojournalists like Meiselas cover throughout their lives.

Susan Meiselas holding a postcard from her show at the SFMoMA.

Mark Murrmann

While plenty of other photographers have similarly dedicated their careers to significant documentary work—Eugene Richards, Sebastião Salgado, Donna Ferrato, Larry Towell, Marcus Bleasdale, among many others—Meiselas stands out as a curator of histories as much as a photographer. From her earliest work, she has strived to find a way to not just make pictures, but include her subjects’ voices and perspectives in the work. One of her earliest projects was 44 Irving St., photographing the other residents in the boarding house in which she lived during graduate school. Not content just to make photos, she had each person write something about their room and living in that house. It was an early exercise in considering the documentary process as much more than just making pictures, a practice she has continued throughout her career.

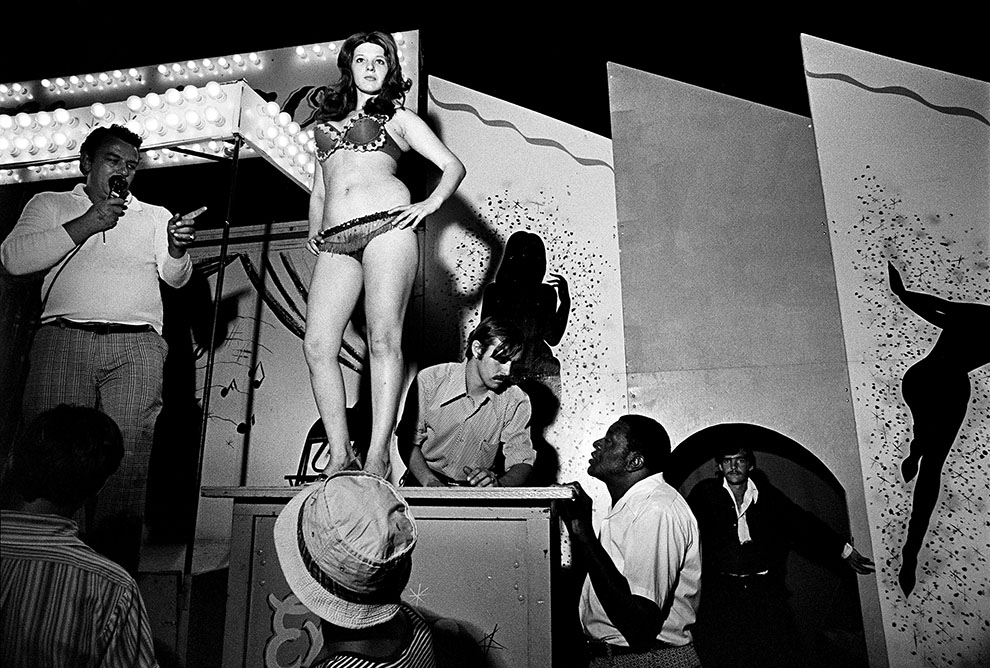

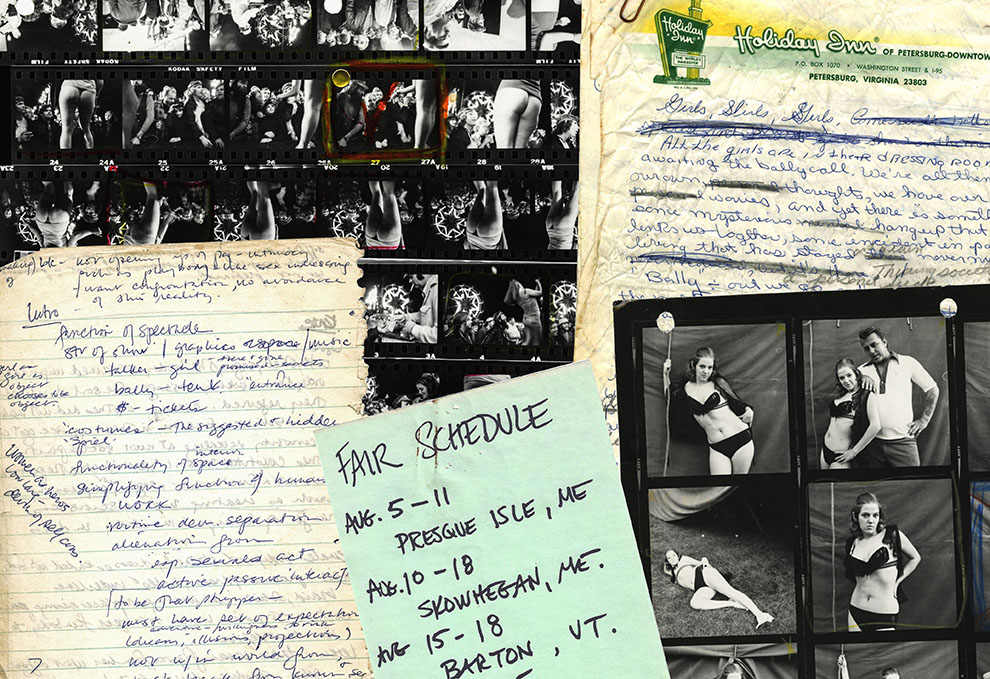

That inclination for deep documentation is on display in her exhibit at the SFMoMA, like early cassette-recorded interviews of the women she photographed for her first book, Carnival Strippers. Notes, ephemera, other evidence of her work make up a core part of the exhibition. For her Nicaragua work, she highlights magazines that originally published the photographs, showcasing the other end of doing work as a documentary photographer—getting the story in front of people. More than most exhibits, it is a 360-degree view of doing documentary work, which involves much more than showing up and taking pictures.

Essex Junction, Vermont. 1973. Lena on the Bally Box. From Carnival Strippers.

Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos

Contact sheets and notes from Carnival Strippers

The carnival stripper photographs preceded her work in Central America, and following her work in Nicaragua and El Salvador through the late ’70s and ’80s, she turned her attention to the Kurdish diaspora, collecting historical and family photos along with documents to more fully explain what—and where—Kurdistan was. The new exhibition uses a map, with personal histories attached to specific locations, as a way to help break the barrier between viewer and subject. It’s one more way in which the work breaks the passive barrier of most documentary work. You are encouraged to engage.

Meiselas asks in her book Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History, “Every picture tells a story and has another story behind it: Who’s photographed? Who made it? Who found it? How did it survive? I wonder what we can know of any particular encounter by looking at such a picture today. We have the object, but it exists separated from the narrative of its making.”

It’s this kind of questioning that drives her retrospective, trying to keep the photographs on the walls firmly attached to the narrative of their making. Included are some of her lesser-seen work, including Archives of Abuse, 1991-1992, in which she worked with the San Francisco Police Department documenting domestic violence, often incorporating photographic evidence from the police in her work. The show brings in pieces of nearly every major social documentary project on which she’s worked. Notable missing work includes her project on the high-end New York S&M club Pandora’s Box, as well as her exceptional coverage of 9/11.

In the book version of Meiselas’ retrospective, Mediations [Damaini/DAP], the process of documentation takes center stage. This isn’t your typically bloated, heavy retrospective—not the exhibit nor the book. Nor is it a typical victory lap or career capper. Mediations is relatively small, with more text than photos. Many of the images are of contact sheets and notebooks, again highlighting the act of documentation. The essays examine Meiselas’ work, the impact it has made in the photo community and in the communities in which she worked.

Northern Iraq. Kurdistan. June, 1992. Widow at mass grave found in Koreme.

Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos

As the title suggests, this retrospective, and the book in particular, focus more on process and impact than simply showcasing her work. It’s refreshing in that they help push the dialogue in the photo community forward, rather than just looking back. It’s quintessential Meiselas. She has spent as much, if not more, of her career behind the scenes in the industry, pushing hard to make it smarter and more inclusive through her efforts in founding the Magnum Foundation, a nonprofit which offers grants to photographers and helps support diversity in photojournalism, as well as pushing the boundaries of storytelling. She also has a record of inspiring and leading new generations of documentarians.

To that end, the exhibition and book individually don’t give nearly enough context to reveal the full depths of her career. But they are both exceptional, giving a taste of the breadth of her work. Taken together, though, the book and exhibition do give a sense of the sincere impact she has—and continues to have—on the world of photojournalism.

El Salvador, 1980. Soldiers search bus passengers along the Northern Highway.

Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos

The Mediations exhibition is on display at the San Francisco Museum of Art through October 21, 2018.