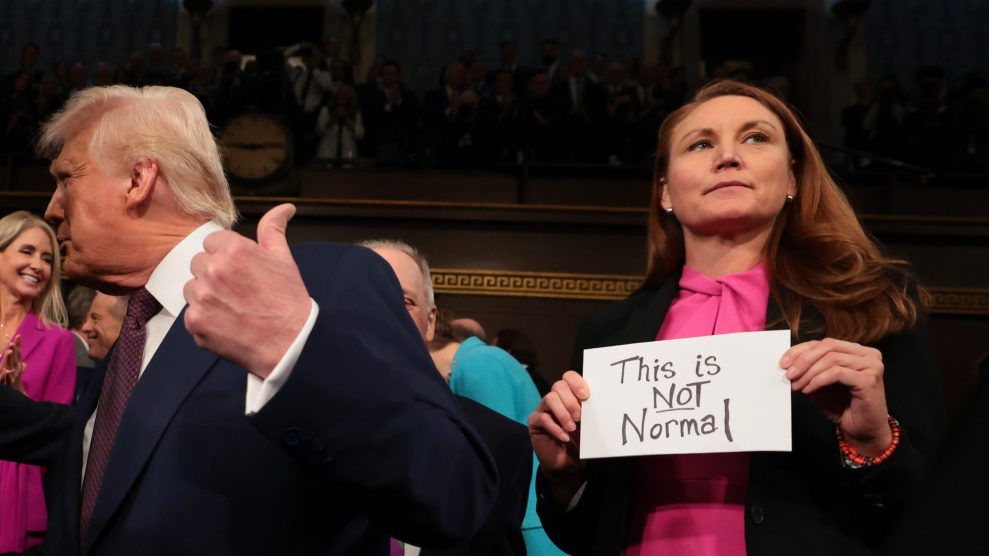

White House press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders conducts a briefing on August 15.Ron Sachs/CNP/ZUMA Wire

This story was originally published by ProPublica.

As the midterm elections approach, Republican state officials and lawmakers have stepped up efforts to block students from voting in their college towns. Republicans in Texas pushed through a law last year requiring voters to carry one of seven forms of photo identification, including handgun licenses but excluding student IDs. In June, the GOP-controlled legislature in North Carolina approved early voting guidelines that have already resulted in closing of polling locations at several colleges. And last month, New Hampshire’s Republican governor signed a law that requires students who vote in the state to also register their cars and obtain driver’s licenses there.

One nationally prominent Republican, however, once took the opposite stance on student voting. As an undergraduate at Ouachita Baptist University in Arkadelphia, Arkansas, Sarah Huckabee—now White House Press Secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders—sued to allow students to vote after being one of more than 900 purged from the county’s rolls.

“It’s almost like taxation without representation,” she said at the time. “They thought that because we were young that they could walk all over us, but obviously that’s not the case.”

Illustrating the adage that politics makes strange bedfellows, the 2002 lawsuit paired a then-20-year-old Sanders with the American Civil Liberties Union. It began, as disputes over student voting often do, with a town-and-gown conflict. Reversing the usual pattern, a Democrat rather than a Republican instigated the student disenfranchisement.

For Sanders, the daughter of Arkansas’ then-governor Mike Huckabee, the little-known episode helped her carve out a niche as a political activist in her own right. It remains relevant today both because of her influential post in the Trump administration and because it suggests that Republican efforts to restrict student voting are largely pragmatic—intended to maximize the party’s electoral chances—and could change as circumstances warrant. It also indicates that Democratic support for on-campus voting may similarly hinge on the expectation that most students lean to the left.

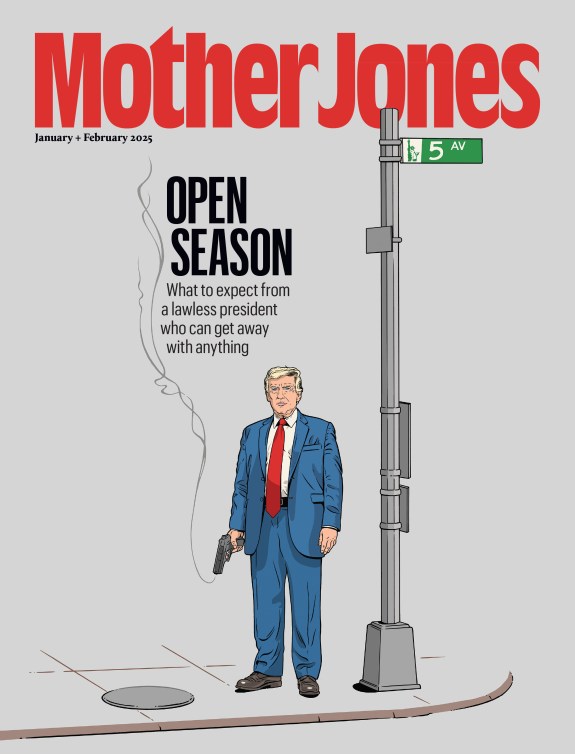

While the Trump administration hasn’t weighed in specifically on student voting rights, it has supported states that impose voter identification requirements or purge voter rolls. By contrast, the Obama administration pushed to expand access to the polls. Contacted by ProPublica, Sanders requested a list of written questions but then did not respond to them.

“It’s not lost on us that Sanders has joined an administration that is actively defending unlawful voter purges and voter disenfranchisement,” said Rita Sklar, who was executive director of the ACLU of Arkansas when it represented Sanders and holds the same position today. “Maybe she can talk to her boss about it.”

The events that cast Sanders as a voting rights advocate stemmed from an election in Clark County, Arkansas, where Ouachita Baptist is located. In 1998, before Sanders enrolled there, an Ouachita junior named Jonathan Huber, who grew up in Louisiana, was elected to the county governing board.

While the student body at OBU, a small, religious college in southwest Arkansas, favored Republicans, the surrounding county historically voted Democratic. Huber, who told ProPublica he was the first Republican to win an election in the county since Reconstruction, credited his victory to the hundreds of college students he helped register to vote.

The students’ electoral muscle angered Floyd Thomas Curry, a Democratic attorney who lived in Huber’s district. In 2002, when Huber—who by then had graduated from Ouachita and settled in the area—was up for re-election to the governing board, Curry sued the county. He argued that, as temporary residents, students did not qualify to vote there.

“It became clear that my right to vote was just going down the drain,” Curry said at the time. “Even if these students voted the way I do, it’s still diluting my vote.”

A circuit court judge agreed. Just two weeks before the election, past the voter registration deadline and with early voting underway, Judge John A. Thomas ordered the county clerk to purge from the voter rolls anyone other than faculty or staff who registered using on-campus addresses, thus disenfranchising Sanders and 911 other students from OBU and neighboring Henderson State University. Thomas’s ruling cited an Arkansas law that temporary residents, including students, should vote in their hometowns—which, for Sanders, was Little Rock.

Sanders’ father, Gov. Mike Huckabee, assailed the decision. In the midst of a successful bid for re-election, he denounced the court order as an “absolute outrage,” “one of the worst things that’s happened in Arkansas politics in a long time,” and an example of the perils of “one-party fiefdom.” Shortly thereafter, he phoned Sklar, the executive director of the ACLU of Arkansas.

“Well, Rita,” Sklar recalled the governor saying. “I guess there’s something else we agree on beyond not executing juveniles.” Huckabee did not respond to requests for comment.

Days later, the ACLU filed a class-action lawsuit in federal district court in Little Rock on behalf of the disenfranchised students, with Sanders and four others named as plaintiffs. “It was an opportunity to bring a fairly standard student voting rights case about residency but in the reverse context where the victims, if you will, were conservative rather than liberal,” said Bryan Sells, then a staff attorney on the ACLU’s Voting Rights Project who represented the students.

The ACLU’s involvement demonstrated its willingness to represent groups on both sides of the political spectrum. “It’s the kind of thing you wish people remembered when they start accusing the ACLU of being the legal arm of the Democratic Party,” Sklar said.

The ACLU contended that the constitutional guarantee of the right to vote overrode the Arkansas statute. While a state may impose reasonable residency restrictions, Sells argued, it cannot presume an entire class of voters—in this case students—are not residents without presenting a compelling reason. The lead plaintiff, Adam Copeland, grew up in foster care and had no home other than his on-campus housing.

Another plaintiff, J.D. Hays Jr., grew up a half-mile away from campus but had registered to vote using his college address. His father taught at OBU. Thomas’ ruling “meant that I couldn’t vote in the county that I grew up in. I didn’t have some other county,” Hays recalled recently. “I couldn’t go home to vote. I was home already.”

Sanders, who had served in high school as secretary of the Arkansas Federation of Teenage Republicans, became the students’ de facto spokesperson with the media, foreshadowing her White House role. A week before the election, US District Court Judge George Howard Jr. ordered the county clerk to restore all purged individuals onto the voter rolls.

“I am very excited and very pleased,” Sanders told the press after her father called her in class to tell her about the ruling. “There’s still a lot to be done.”

Benefiting from the student vote, Huber was re-elected and went on to serve in the position for eight more years; he’s now a lawyer and licensed real estate broker in Clark County. Sanders graduated from Ouachita in 2004.

Republican efforts to suppress student voting became more prevalent after college-age turnout spiked in the 2008 election, contributing to Obama’s victory, said Dale Ho, director of the ACLU’s Voting Rights Project. In 2014, Florida’s division of elections under a Republican secretary of state barred counties from placing early voting locations on college campuses. Saying that this policy created “a stark pattern of discrimination,” a federal judge last month ruled that campus buildings in Florida can be open for early voting this fall.

Sells, Sanders’ former ACLU attorney, said he hopes that her views haven’t changed and that she could be a voice within the Trump administration for broadening access to the ballot box. “If the occasion ever comes up in her job where she’s asked about voting rights, I hope she recognizes how important it was to her and to her fellow plaintiffs at the time, how important it is to other people who are seeking to vindicate their voting rights,” he said.

Sixteen years later, Floyd Thomas Curry now regrets seeking to suppress student votes. “When I realized I was opposed by the ACLU, I thought, ‘Gee, maybe I’m not right,'” Curry said in a recent interview. “In retrospect, I was dead wrong. It was not my proudest moment.”

The voting rights that Sanders helped Ouachita and Henderson students regain may still be paying dividends for Republicans. In 2016, Trump carried the once reliably Democratic county by 9 percentage points.