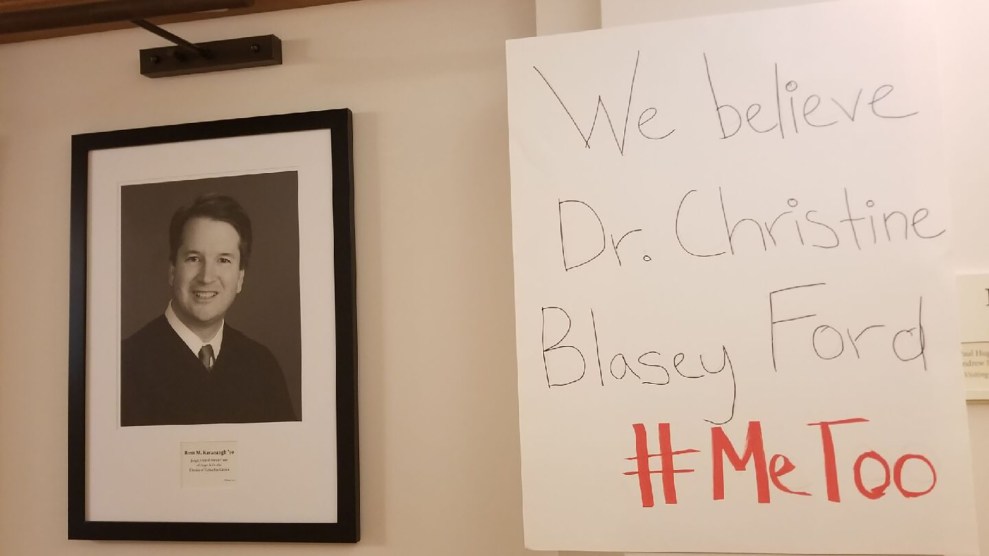

Yale Law School students place a protest sign next to a photograph of alum and Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh on campus.Catherine McCarthy, Yale Law School

Just a few weeks ago, the nomination of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court appeared to be yet another coup for Yale Law School, as one more of its graduates would soon take his place on the nation’s highest court. Kavanaugh, a DC Circuit Court judge, has taught courses at Yale Law and frequently hires clerks from the school. Over the summer, the school released statements from its best-known faculty showering praise on Kavanaugh. “I can personally attest that, in addition to his government and judicial service, Judge Kavanaugh has been a longtime friend to many of us in the Yale Law School community,” Dean Heather Gerken said.

A few months later, with Kavanaugh’s nomination in limbo amid allegations of sexual assault, Yale Law School has been brought to a standstill. Classes were canceled Monday afternoon after students protested Kavanaugh by refusing to attend. Gerken and students met at a town hall-style event Tuesday to begin a dialogue about how the law school can evolve in the #MeToo era. Kavanaugh has become a symbol of what students allege is the school’s “complicity” in allowing federal judges to get away with harassment and assault. Kavanaugh’s nomination has gone from representing Yale’s prestige to highlighting deep-rooted problems.

Amid the allegations of Kavanaugh’s sexual misconduct came reports that he preferred attractive female clerks and was abetted by Yale law professors. According to the Guardian, professor Amy Chua had told a group of students it was “no accident” that his female clerks “look like models.” Chua, the Guardian reported, had advised a student to dress in an “outgoing” way for her interview with Kavanaugh. (Chua denied this.) Chua’s husband, Yale law professor Jed Rubenfeld, reportedly told the same student that Kavanaugh preferred female clerks with a certain “look.”

When Kavanaugh was nominated to the Supreme Court, Chua wrote an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal supporting Kavanaugh as a “mentor to women” and noted that she had placed 10 clerks with him in the last decade—eight of them women, including her own daughter.

Last Thursday, a campus group called Yale Law Women organized a discussion between students and faculty on the Kavanaugh nomination and the #MeToo movement. According to several attendees, the event quickly soured as it turned to the internal policies and the clerkship application process at Yale. The discussion touched on Judge Alex Kozinski, a federal appeals court judge who frequently took on clerks from Yale, including Kavanaugh, and who resigned last year after more than a dozen women accused him of sexual harassment or assault. According to students in the room, the existence of an ongoing investigation into Rubenfeld’s treatment of students came up and multiple attendees were in tears.

“I suspect that if it had gone differently, there would not have been 260, 270 people sitting in the hallway today in silent protest,” one student who attended Thursday’s meeting and requested anonymity told Mother Jones.

Several students said that a central premise of the recent protests has been Yale’s complicity in power dynamics that allow judges to harass clerks and colleagues. Yale, consistently ranked the number-one law school in the country, has not found a way to hold powerful men accountable. “The power that it holds is so immense, and to not have used that power prevent, to the extent it could, to not have used that power to prevent Judge Kozinski from holding so much power or getting away with these things, that’s why people are in the halls today and that’s why people are protesting,” the student said. “Because that feels enormously damning of this place.”

Yale law professors, according to students, have denied that they were aware of Kozinski’s behavior, even though it was an open secret in the legal world, according to numerous lawyers who have stated knowledge of his serial harassment. One student had heard rumors that Yale and other top law schools were careful to send mostly male students his way as clerks in order to spare women his abuse. But this response, if true, disadvantaged women because Kozinski was a prestigious judge whose clerks regularly went on to clerk at the Supreme Court. An attorney in Washington who graduated from a top law school told Mother Jones that rumor has been around for years. Indeed, over the last several years, Kozinski’s clerks who went on to clerk at the Supreme Court were overwhelmingly men.

There’s reason to believe Kavanaugh knew about Kozinski’s behavior. Kavanaugh clerked for Kozinski in the early 1990s, and they remained close. For years, Kozinski maintained an email list of friends and associates to whom he sent distasteful sexual jokes. During his confirmation hearing, Kavanaugh testified under oath that he couldn’t remember if he was on the email list—though it’s unlikely he was not. Under oath, Kavanaugh testified that he knew nothing of Kozinski’s behavior until press reports about it last year.

Signs criticizing Yale Law School popped up around campus after Thursday’s meeting ended in frustration. Yale Law School “is a model of complicity,” read one.

https://twitter.com/emilyjodell/status/1043150245142712321

Two signs flanked a photograph of Kavanaugh in a Yale hallway. One read, “We still believe Anita Hill.” The other read, “We believe Dr. Christine Blasey Ford #MeToo.”

Protest signs were placed next to a photograph of Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh at Yale Law School last week.

Catherine McCarthy/Yale Law School

“Staring down the barrel of this profession and seeing how ugly it can sometimes be is hard to reckon with as a second-year law student,” said student Samantha Peltz. By Friday afternoon, professors had begun to cancel classes. Soon, students had organized themselves into a new group, Yale Law Students Demanding Better. On Monday, about 100 students arrived in Washington to protest Kavanaugh’s confirmation, while about 260 participated in a silent demonstration on campus.

Yale Law students are DONE with our institution’s complicity in pushing forward this nominee.

Is there nothing that matters more to @YaleLawSch than power and prestige? #IBelieveChristine #IBelieveDeborah #metoo pic.twitter.com/Yw6U3Dd3dy

— Dana Bolger (@danabolger) September 24, 2018

On Tuesday, students met with the dean in what organizers described as the beginning of a dialogue about Yale’s role in the #MeToo movement. The bigger conversation, the organizers said, should include Yale’s relationship with judges and its role in the process of applying for clerkships, which can set someone up for a lifetime of prestige in the legal profession. If there’s a judge with a reputation for harassment or worse, one organizer said, there should be a mechanism for reporting that, and the school should know which professors continue to send students to that judge for clerkships. Additionally, the organizer said, Yale should grapple with its responsibility when it comes to letting judges get away with inappropriate behavior.

“Yale Law School trains and produces people who have serious impact on the world,” said Briana Clark, a current student. “So it needs to recognize, one, that it does that, and then hopefully [begin] holding them to a standard that Yale can be proud of.”

“It’s so incredibly part of this larger conversation that we’re having as a nation about things that people used to get away with,” one student involved in organizing the events told Mother Jones. “And the things that it was OK to overlook because a judge was really powerful or a judge was your friend are just not OK to do anymore.”